In the pantheon of personal computing pioneers, certain names dominate the narrative: Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, Bill Gates. Yet the early microcomputer industry was built by dozens of brilliant engineers and entrepreneurs whose contributions, while perhaps less celebrated, were no less significant. Among these figures stands George C. Morrow, a man described by Richard Dalton in the Whole Earth Software Catalog as "one of the microcomputer industry's iconoclasts." His journey from high school dropout to computer industry pioneer to jazz preservationist tells a uniquely American story of reinvention, innovation, and passion.

From Detroit to Stanford: An Unconventional Path

George Morrow was born on January 30, 1934, in Detroit, Michigan. His early life followed an unconventional trajectory that would later inform his maverick approach to business. Morrow dropped out of high school, a decision that might have closed doors for others. But at the age of 28, driven by intellectual curiosity, he made the remarkable decision to return to education.

Morrow earned a bachelor's degree in physics from Stanford University, one of the nation's most prestigious institutions. He followed this with a master's degree in mathematics from the University of Oklahoma. Not content to stop there, he pursued doctoral studies in mathematics at the University of California, Berkeley. It was at Berkeley that Morrow's life took its decisive turn. Working as a programmer in the university's computer lab, he became captivated by the emerging world of computing. The pursuit of a PhD in mathematics gave way to a new passion that would define the rest of his career.

The Homebrew Computer Club and the Birth of an Industry

The year 1975 marked a watershed moment in computing history. The MITS Altair 8800 appeared on the cover of Popular Electronics, igniting the imagination of hobbyists and engineers across the country. In the San Francisco Bay Area, these enthusiasts began gathering at the Homebrew Computer Club, an informal group that would spawn an extraordinary number of future industry leaders.

Morrow became an active member of this legendary collective, documented extensively in Fire in the Valley. Among his fellow members were Steve Wozniak, who would co-found Apple; Harry Garland and Roger Melen of Cromemco; Adam Osborne of Osborne Computer; Lee Felsenstein, designer of the Osborne 1; and Bob Marsh of Processor Technology. The club served as an incubator for ideas, a forum for technical exchange, and a launching pad for commercial ventures.

From Morrow's Microstuff to Thinker Toys

Starting in 1976, Morrow began designing and selling computer parts and accessories. His first venture was Morrow's Microstuff, which sold memory boards for the Altair 8800 via mail order. His initial product was an Intel 8080 board featuring an octal-notation keypad, but it proved unappealing to hobbyists who preferred the binary notation and flip switches of the Altair itself.

Undeterred, Morrow pivoted to what would become his signature contribution: storage solutions. He began selling floppy disk drives for S-100 machines, packaging them as complete systems that included an 8-inch external drive, a controller board, the CP/M operating system, and CBASIC. This bundle proved enormously popular, establishing Morrow as a significant player in the nascent industry.

Morrow rebranded his company as Thinker Toys, a name that captured the playful yet serious nature of the hobbyist computing world. However, the toy company that manufactured Tinkertoys took exception to the similar name and threatened legal action. Morrow was forced to rename his business once more, this time as Morrow Designs—the name by which it would become best known. The company set up operations at 600 McCormick Street in San Leandro, California.

Bringing Mainframe Concepts to Microcomputers

What set Morrow apart from many competitors was his willingness to bring sophisticated engineering concepts from the mainframe world to microcomputers. The Disk Jockey/DMA (DJDMA) floppy disk controller exemplified this philosophy. As the company's technical documentation explained: "The idea of an intelligent I/O channel was first implemented by IBM on their famous 370 mainframes. Now for the first time, this powerful concept has been implemented on the S100 bus."

The DJDMA featured its own Z-80 4MHz microprocessor dedicated to supervising data transfers between disk drives and system memory. This "channel concept," borrowed directly from IBM's mainframe architecture, allowed the controller to operate independently of the main CPU. The documentation boasted: "All in all, there is nothing on the S-100 bus in the way of a floppy disk controller that comes anywhere near the performance and versatility of the DJDMA. For that matter, we here at Morrow Designs know of no other floppy disk controller on any bus that can match the DJDMA in price, power, performance, and flexibility."

This wasn't mere marketing hyperbole. The controller supported both 8-inch and 5¼-inch drives, could accommodate up to eight drives simultaneously, and featured programmable bipolar LSI logic that could read and write media with almost any format. The engineering approach reflected Morrow's belief that microcomputer users deserved the same sophisticated I/O handling that mainframe users enjoyed.

Morrow Designs also ventured into hard disk storage with products like the Discus M26, a complete mass storage subsystem with a 14-inch Winchester-type hard disk offering 26 million bytes of formatted storage—an enormous capacity for the era. The system could be expanded to 104 million bytes with four drives. The company was already planning cassette tape backup systems for 1980, recognizing the data security challenges posed by non-removable media.

The S-100 Bus and IEEE-696: Building Industry Standards

One of Morrow's most enduring contributions to computing was his work on the S-100 bus standard. The S-100 bus—named for its 100-pin connector—had originated with the Altair 8800. While it enabled a thriving ecosystem of compatible boards and peripherals, the lack of formal standardization created compatibility problems as manufacturers interpreted the bus specifications differently.

Morrow recognized that the industry needed rigorous standards to mature. The first symposium on the S-100 bus was held on November 20, 1976, at Diablo Valley College, moderated by Jim Warren with a panel that included Morrow, Harry Garland, and Lee Felsenstein. In July 1979, Morrow joined Kells Elmquist, Howard Fullmer, and David Gustavson in publishing a "Standard Specification for S-100 Bus Interface Devices," extending the data path to 16 bits and the address path to 24 bits.

The IEEE 696 Working Group continued developing the specification, which was approved by the IEEE Computer Society on June 10, 1982, and by ANSI on September 8, 1983 as IEEE Std 696-1983. Morrow was, by many accounts, the person most responsible for the design, specification, and approval of this standard. His DJDMA documentation reflected this commitment to standards: "A great deal of care has been taken in the design of the interface circuitry so it conforms in every detail to this new standard and still allows the controller to work well with existing systems designed before the standardization effort was started."

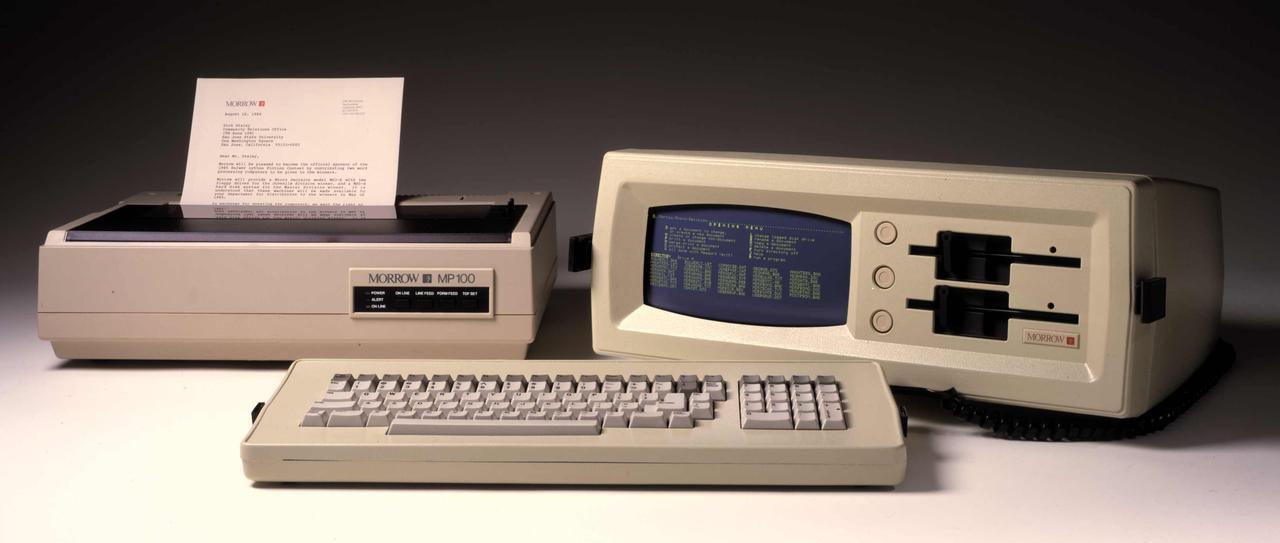

The Decision 1 and Micro Decision: Computing for Everyone

In 1979, George Morrow and his wife Michiko Jean formally incorporated Morrow Designs. The company's product line expanded to include complete computer systems aimed at making business computing affordable.

The Decision 1 represented the high end of Morrow's offerings. According to the December 1982 price list, the base D1 model sold for \$2,395 and featured an S-100 (IEEE 696) 14-slot motherboard, Z80 CPU, real-time CMOS clock/calendar chip, programmable interrupt controller, three RS232C serial ports, one parallel printer port, and 64K of high-speed static RAM expandable to a full megabyte. The top-of-the-line D3C model, with a 16-megabyte hard disk, commanded \$5,400. The company also offered multi-user upgrade kits with the Micronix operating system, enabling small businesses to share a single computer among multiple terminals.

But it was the Micro Decision line, introduced in 1982, that best exemplified Morrow's commitment to affordability. The MD1 started at just \$1,195 and included a Z80A CPU running at 4MHz, 64K of RAM, two RS232C serial ports, a floppy disk controller supporting up to four drives, and a complete software bundle: CP/M 2.2, Microsoft BASIC 80, the company's own BaZic interpreter (compatible with NorthStar BASIC), WordStar word processor, LogiCalc spreadsheet, and Correct-It spelling checker.

The MD2, with two single-sided drives providing 400K of storage, sold for \$1,545. The MD3, featuring two double-sided drives with 768K total storage plus the Personal Pearl database manager, cost \$1,695. Optional terminals—the MDT20 in beige or MDT50 in black—added \$595. These were remarkable prices for complete, software-bundled systems at a time when competing products often cost significantly more.

Bankruptcy and Beyond

As the IBM PC and its clones came to dominate the market, Morrow Designs faced an existential challenge. The company's CP/M-based systems, however excellent, were increasingly seen as outdated. In 1984, Morrow released the Pivot, an IBM-compatible portable computer, licensing the design to Zenith Electronics Corporation for \$1.2 million.

The Zenith deal, ironically, hastened the company's demise. In 1986, Zenith won a \$27 million contract with the Internal Revenue Service to supply computers based on Morrow's design. But the terms of the licensing agreement and the company's mounting debts proved unsustainable. On March 11, 1986, just weeks after Zenith won the IRS contract, Morrow Designs filed for bankruptcy.

Computer Chronicles and a Second Act

Even as his company struggled, Morrow found a new platform for his expertise. He became a co-host of Computer Chronicles, a public television program that explained computing to general audiences. Morrow appeared in over 40 episodes between 1985 and 1995, sharing his deep knowledge of hardware, software, and industry trends with viewers across the country. His appearances revealed the same qualities that had defined his career: technical depth combined with an ability to communicate complex ideas clearly, and an iconoclastic perspective that questioned industry assumptions.

Following the collapse of Morrow Designs, George Morrow turned to a passion he had nurtured throughout his life: jazz and big band music from the 1920s and 1930s. He assembled one of the largest private collections of 78 RPM records in the country, eventually exceeding 70,000 items, with a particular focus on rare dance and jazz recordings from the pre-war era.

Applying the same engineering mindset that had driven his computer work, he developed a sophisticated system to digitize and restore these fragile shellac recordings. His son John recalled that his father would labor for hours or even days over a single recorded song until satisfied with the restored version. Morrow released these painstakingly restored recordings under his own label, Old Masters, preserving an important piece of American musical heritage for future generations.

Legacy

George Morrow died on May 7, 2003, at his home in San Mateo, California, from complications of aplastic anemia. He was 69 years old. He was survived by his wife Michiko Jean, sons John and William, and daughter Kelly.

Morrow's contributions to computing extend far beyond the products that bore his name. His work on the IEEE-696 standard helped transform a hobbyist ecosystem into a professional industry. His decision to bring mainframe I/O concepts to microcomputers pushed the entire field forward. His commitment to affordable, software-bundled systems anticipated the value-driven approach that would eventually democratize personal computing.

The archive of Morrow Designs documentation—including technical manuals, BIOS source code, price lists, and product literature—survives as a resource for historians and retrocomputing enthusiasts. These documents reveal not just the products themselves but the engineering philosophy behind them: a belief that microcomputer users deserved sophisticated, well-documented systems at fair prices.

Perhaps most importantly, Morrow embodied the spirit of the early microcomputer industry: the conviction that small teams of dedicated engineers could build transformative technologies, that standards and cooperation could coexist with competition, and that computing should be accessible to everyone, not just institutions and corporations.

Further Reading

- Fire in the Valley: The Birth and Death of the Personal Computer by Michael Swaine and Paul Freiberger — The definitive history of the Homebrew Computer Club and the personal computer revolution.

- Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution by Steven Levy — A classic account of the hacker ethic and the people who built the early computer industry.

- The Soul of a New Machine by Tracy Kidder — Pulitzer Prize-winning chronicle of a computer engineering team, capturing the intensity of the era.