In my previous post, I documented building an LLVM backend for the Z80 processor. The backend worked — simple LLVM IR compiled to valid Z80 assembly. But that post ended with a sobering admission: Rust's core library remained out of reach, its abstractions overwhelming the constraints of 1976 hardware.

This post picks up where that one left off. The question nagging at me was simple: can we actually compile real Rust code into Z80 assembly? Not just hand-crafted LLVM IR, but genuine Rust source files with functions and variables and all the conveniences we expect from a modern language?

The answer is yes. But getting there required more RAM than any Z80 system ever had, a creative workaround that sidesteps Rust's build system entirely, and a willingness to accept that sometimes the elegant solution isn't the one that works.

The Hardware Reality Check

Before diving into the technical details, I need to address something that caught me off guard: the sheer computational resources required to compile code for an 8-bit processor.

My first attempt was on my M3 Max MacBook Pro. The machine is no slouch — 64GB of unified memory, fast SSD, Apple's impressive silicon. Building LLVM with the Z80 backend worked fine. Building stage 1 of the Rust compiler worked, albeit slowly. But when I tried to build Rust's core library for the Z80 target, the process crawled. After watching it churn for hours with no end in sight, I gave up.

The next attempt used a Linux workstation with 32GB of RAM. This seemed reasonable — surely 32GB is enough to compile code for a processor with a 64KB address space? It wasn't. The build process hit out-of-memory errors during the compilation of compiler_builtins, a Rust crate that provides low-level runtime functions.

To understand why, you need to know what compiler_builtins actually does. When you write code like let x: u64 = a * b;, and your target processor doesn't have native 64-bit multiplication (the Z80 doesn't even have 8-bit multiplication), something has to implement that operation in software. That something is compiler_builtins. It contains hundreds of functions: software implementations of multiplication, division, floating-point operations, and various other primitives that high-level languages take for granted. Each of these functions gets compiled, optimized, and linked into your final binary.

For the Z80, every one of these functions presents a challenge. 64-bit division on an 8-bit processor expands into an enormous sequence of instructions. The LLVM optimizer works hard to improve this code, and that optimization process consumes memory — lots of it.

The machine that finally worked was a dedicated build server:

OS: Ubuntu 24.04.3 LTS x86_64 Host: Gigabyte G250-G51 Server CPU: Intel Xeon E5-2697A v4 (64 cores) @ 3.600GHz Memory: 252GB DDR4 GPU: 4x NVIDIA Tesla P40 (unused for compilation)

With 252GB of RAM and 64 cores, the build finally had room to breathe. LLVM with Z80 support built in about 45 minutes. The Rust stage 1 compiler built in 11 minutes. And when we attempted to build compiler_builtins for Z80, memory usage peaked at 169GB.

Let that sink in: compiling runtime support code for a processor with 64KB of addressable memory required 169GB of RAM. The ratio is absurd — we needed 2.6 million times more memory to compile the code than the target system could ever access. This is what happens when modern software toolchains, designed for 64-bit systems with gigabytes of RAM, encounter hardware from an era when 16KB was a luxury.

The Naive Approach and Why It Fails

With our beefy build server ready, the obvious approach was to build Rust's core library for the Z80 target. The core library is Rust's foundation — it provides basic types like Option and Result, fundamental traits like Copy and Clone, and essential operations like memory manipulation and panicking. Unlike std, which requires an operating system, core is designed for bare-metal embedded systems. If anything could work on a Z80, surely core could.

The first obstacle was unexpected. Rust's build system uses a crate called cc to compile C code and detect target properties. When we ran the build, it immediately failed:

error occurred in cc-rs: target `z80-unknown-none-elf` had an unknown architecture

The cc crate maintains a list of known CPU architectures, and Z80 wasn't on it. The fix was simple — a one-line patch to add "z80" => "z80" to the architecture matching code — but we had to apply it to every version of cc in the cargo registry cache. Not elegant, but effective.

With that patched, the build progressed further before hitting a more fundamental problem:

rustc-LLVM ERROR: unable to legalize instruction: %35:_(s16) = nneg G_UITOFP %10:_(s64)

This error comes from LLVM's GlobalISel pipeline, specifically the Legalizer. To understand it, I need to explain how LLVM actually turns high-level code into machine instructions.

What is GlobalISel and Why Does It Matter?

When you compile code with LLVM, there's a critical step called "instruction selection" — the process of converting LLVM's abstract intermediate representation (IR) into concrete machine instructions for your target CPU. This is harder than it sounds. LLVM IR might say "add these two 32-bit integers," but your CPU might only have 8-bit addition, or it might have three different add instructions depending on whether the operands are in registers or memory.

Historically, LLVM used a framework called SelectionDAG for this task. SelectionDAG works, but it operates on individual basic blocks (straight-line code between branches) and makes decisions that are hard to undo later. For well-established targets like x86 and ARM, SelectionDAG is mature and produces excellent code. But for new or unusual targets, it's difficult to work with.

GlobalISel (Global Instruction Selection) is LLVM's modern replacement. The "Global" in the name refers to its ability to see across basic block boundaries, making better optimization decisions. More importantly for our purposes, GlobalISel breaks instruction selection into distinct, understandable phases:

-

IRTranslator: Converts LLVM IR into generic machine instructions. These instructions have names like

G_ADD(generic add),G_LOAD(generic load), andG_UITOFP(generic unsigned integer to floating-point conversion). At this stage, the code is still target-independent —G_ADDdoesn't know if it'll become an x86ADD, an ARMadd, or a Z80ADD A,B. -

Legalizer: This is where target constraints enter the picture. The Legalizer transforms operations that the target can't handle into sequences it can. If your target doesn't support 64-bit addition directly, the Legalizer breaks it into multiple 32-bit or 16-bit additions. If your target lacks a multiply instruction (hello, Z80), the Legalizer replaces multiplication with a function call to a software implementation.

-

RegBankSelect: Assigns each value to a register bank. For the Z80, this means deciding whether something lives in 8-bit registers (A, B, C, D, E, H, L) or 16-bit register pairs (BC, DE, HL). This phase is crucial for the Z80 because using the wrong register bank means extra move instructions.

-

InstructionSelector: Finally converts the now-legal, register-bank-assigned generic instructions into actual target-specific instructions.

G_ADDbecomesADD A,BorADD HL,DEdepending on the operand types.

For the Z80 backend, GlobalISel was the right choice. It gave us fine-grained control over how operations get lowered on extremely constrained hardware. The downside is that every operation needs explicit handling — if the Legalizer doesn't know how to transform a particular instruction for Z80, compilation fails.

The error we hit was in the Legalizer. The G_UITOFP instruction converts an unsigned integer to floating-point. In this case, it was trying to convert a 64-bit integer to a 16-bit half-precision float. This operation appears deep in Rust's core library, in the decimal number parsing code used for floating-point literals.

The Z80 has no floating-point hardware whatsoever. It can't even do integer multiplication in a single instruction. Teaching LLVM to "legalize" 64-bit-to-float conversions on such constrained hardware would require implementing software floating-point operations — a significant undertaking that would generate hundreds of Z80 instructions for a single high-level operation.

Even setting aside the floating-point issue, we encountered another class of failures: LLVM assertion errors in the GlobalISel pipeline when handling complex operations. These manifested as crashes with messages about register operand sizes not matching expectations. The Z80 backend is experimental, and its GlobalISel support doesn't cover every edge case that Rust's core library exercises.

The fundamental problem became clear: Rust's core library, while designed for embedded systems, assumes a level of hardware capability that the Z80 simply doesn't have. It assumes 32-bit integers work efficiently. It assumes floating-point parsing is reasonable. It assumes the register allocator can handle moderately complex control flow.

The Workaround: Cross-Compile and Retarget

When the direct path is blocked, you find another way around.

The key insight is that LLVM IR (Intermediate Representation) is largely target-agnostic. When Rust compiles your code, it first generates LLVM IR, and then LLVM transforms that IR into target-specific assembly. The IR describes your program's logic — additions, function calls, memory accesses — without committing to a specific instruction set.

This suggests a workaround: compile Rust code to LLVM IR using a different target that Rust fully supports, then manually retarget that IR to Z80 and run it through our Z80 LLVM backend.

For the donor target, I chose thumbv6m-none-eabi — the ARM Cortex-M0, a 32-bit embedded processor. This target is well-supported in Rust's ecosystem, and crucially, it's a no_std target designed for resource-constrained embedded systems. The generated IR would be reasonably close to what we'd want for Z80, minus the data layout differences.

The workflow looks like this:

- Write Rust code with

#![no_std]and#![no_main] - Compile for ARM:

cargo +nightly build --target thumbv6m-none-eabi -Zbuild-std=core - Extract the LLVM IR from the build artifacts (the

.llfiles) - Modify the IR's target triple and data layout for Z80

- Compile to Z80 assembly:

llc -march=z80 -O2 input.ll -o output.s

The data layout change is important. ARM uses 32-bit pointers; Z80 uses 16-bit pointers. The Z80 data layout string is:

e-m:e-p:16:8-i16:8-i32:8-i64:8-n8:16

This tells LLVM: little-endian, ELF mangling, 16-bit pointers with 8-bit alignment, native types are 8-bit and 16-bit. When we retarget the IR, we need to update this layout and the target triple to z80-unknown-unknown.

Is this elegant? No. It's a hack that bypasses Rust's proper build system. But it works, and sometimes working beats elegant.

Hello Z80 World

Let's put this into practice with the classic first program.

Here's the Rust source code:

#![no_std] #![no_main] use core::panic::PanicInfo; // Memory-mapped serial output at address 0x8000 const SERIAL_OUT: *mut u8 = 0x8000 as *mut u8; #[inline(never)] #[no_mangle] pub extern "C" fn putchar(c: u8) { unsafe { core::ptr::write_volatile(SERIAL_OUT, c); } } #[no_mangle] pub extern "C" fn hello_z80() { putchar(b'H'); putchar(b'e'); putchar(b'l'); putchar(b'l'); putchar(b'o'); putchar(b' '); putchar(b'Z'); putchar(b'8'); putchar(b'0'); putchar(b'!'); putchar(b'\r'); putchar(b'\n'); } #[panic_handler] fn panic(_: &PanicInfo) -> ! { loop {} }

This is genuine Rust code. We're using core::ptr::write_volatile for memory-mapped I/O, the extern "C" calling convention for predictable symbol names, and #[no_mangle] to preserve function names in the output. The #[inline(never)] on putchar ensures it remains a separate function rather than being inlined into the caller.

After compiling to ARM IR and retargeting to Z80, we run it through llc. The output is real Z80 assembly:

.globl putchar putchar: ld de,32768 ; Load address 0x8000 push de pop hl ; DE -> HL (address now in HL) ld (hl),a ; Store A register to memory ret .globl hello_z80 hello_z80: push ix ; Save frame pointer ld ix,0 add ix,sp ; Set up stack frame dec sp ; Allocate 1 byte on stack ld a,72 ; 'H' call putchar ld a,101 ; 'e' call putchar ld a,108 ; 'l' ld (ix+-1),a ; Save 'l' to stack (optimization!) call putchar ld a,(ix+-1) ; Reload 'l' for second use call putchar ld a,111 ; 'o' call putchar ld a,32 ; ' ' call putchar ld a,90 ; 'Z' call putchar ld a,56 ; '8' call putchar ld a,48 ; '0' call putchar ld a,33 ; '!' call putchar ld a,13 ; '\r' call putchar ld a,10 ; '\n' call putchar ld sp,ix ; Restore stack pop ix ; Restore frame pointer ret

This is valid Z80 assembly that would run on real hardware. The putchar function loads the serial port address into the HL register pair and stores the character from the A register. The hello_z80 function calls putchar twelve times, once for each character in "Hello Z80!\r\n".

Notice something interesting: the compiler optimized the duplicate 'l' character. Instead of loading 108 into the A register twice, it saves the value to the stack after the first use and reloads it for the second. This is LLVM's register allocator at work, recognizing that reusing a value from the stack is cheaper than reloading an immediate. The Z80 backend is generating genuinely optimized code.

Running on (Emulated) Hardware

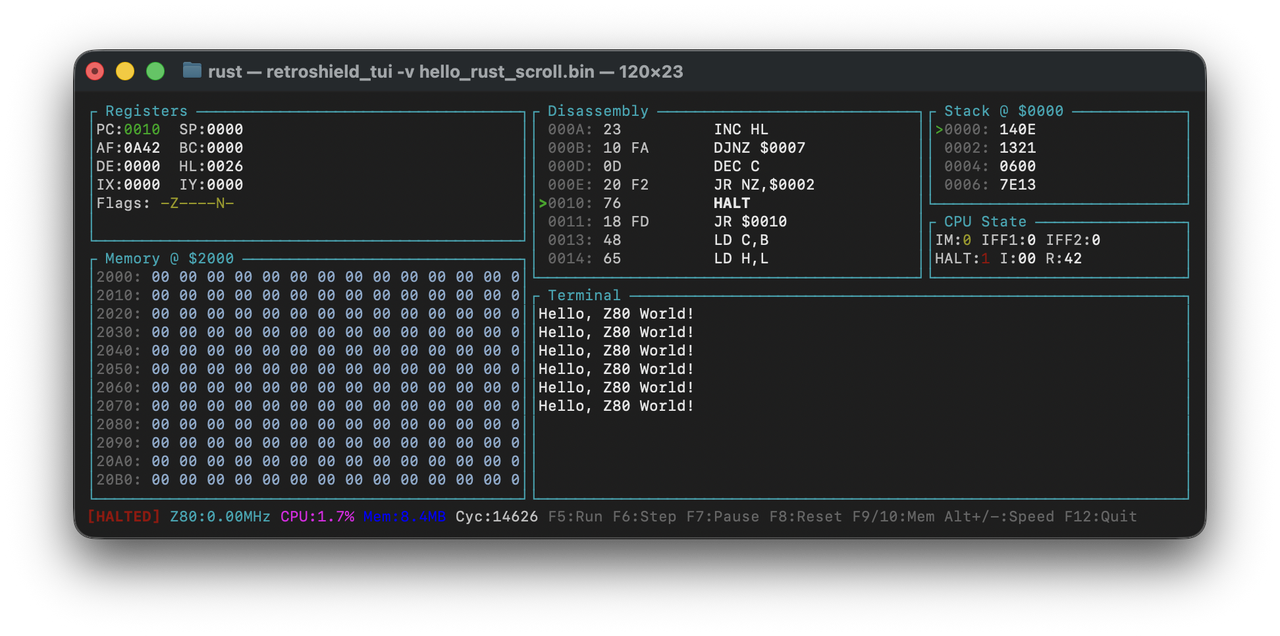

Generating assembly is satisfying, but seeing it actually execute closes the loop. I have a Rust-based Z80 emulator that I use for testing RetroShield firmware. It emulates the Z80 CPU along with common peripheral chips, including the MC6850 ACIA serial chip that my physical hardware uses.

To run our Hello World, we need to adapt the memory-mapped I/O to use the ACIA's port-based I/O instead. The MC6850 uses port $80 for status and port $81 for data. A proper implementation waits for the Transmit Data Register Empty (TDRE) bit before sending each character:

; Hello Z80 World - Compiled from Rust via LLVM ; Adapted for MC6850 ACIA serial output ACIA_STATUS: equ $80 ACIA_DATA: equ $81 org $0000 _start: ld hl, MESSAGE ld b, MESSAGE_END - MESSAGE print_loop: wait_ready: in a, (ACIA_STATUS) and $02 ; Check TDRE bit jr z, wait_ready ld a, (hl) out (ACIA_DATA), a inc hl djnz print_loop halt_loop: halt jr halt_loop MESSAGE: defb "Hello, Z80 World!", $0D, $0A MESSAGE_END:

This is the essence of what our Rust code does, translated to the actual hardware interface. The infinite loop at the end mirrors Rust's loop {} — on bare metal, there's nowhere to return to.

Assembling with z80asm produces a 39-byte binary. Running it in the emulator:

$ ./retroshield -d -c 10000 hello_rust.bin Loaded 39 bytes from hello_rust.bin Starting Z80 emulation... Hello, Z80 World! CPU halted at PC=0011 after 1194 cycles

The program executes in 1,194 Z80 cycles — roughly 300 microseconds at the original 4MHz clock speed. The complete pipeline works:

- Rust source code → compiled to LLVM IR via rustc

- LLVM IR → retargeted to Z80 and compiled to assembly

- Z80 assembly → assembled to binary with z80asm

- Binary → executed in the Z80 emulator

The 39-byte binary breaks down to about 20 bytes of executable code and 19 bytes for the message string. This is exactly what bare-metal #![no_std] Rust should produce — tight, efficient code with zero runtime overhead.

What Works and What Doesn't

Through experimentation, we've mapped out the boundaries of what the Z80 backend handles well.

Works reliably:

- 8-bit arithmetic: addition, subtraction, bitwise operations. These map directly to Z80 instructions like

ADD A,BandAND B. - 16-bit arithmetic: addition and subtraction use the Z80's 16-bit register pairs (HL, DE, BC) efficiently.

- Memory operations: loads and stores generate clean

LD (HL),AandLD A,(HL)sequences. - Function calls: the calling convention uses registers efficiently, avoiding unnecessary stack operations for simple cases.

- Simple control flow: conditional branches and unconditional jumps work as expected.

Works but generates bulky code:

- 32-bit arithmetic: every 32-bit operation expands into multiple 16-bit operations with careful carry flag handling. A 32-bit addition becomes a sequence that would make a Z80 programmer wince.

- Multiplication: even 8-bit multiplication requires a library call to

__mulhi3since the Z80 lacks a multiply instruction.

Breaks the register allocator:

- Loops with phi nodes: in LLVM IR, loops use phi nodes to represent values that differ depending on which path entered the loop. Complex phi nodes exhaust the Z80's seven registers, causing "ran out of registers" errors.

- Functions with many live variables: if you need more than a handful of values alive simultaneously, the backend can't handle it.

Not supported:

- Floating-point operations: no legalization rules exist for converting the Z80's lack of FPU into software equivalents.

- Complex

corelibrary features: iterators, formatters, and most of the standard library infrastructure trigger unsupported operations.

The Calling Convention

Through testing, we've empirically determined how our Z80 backend passes arguments and returns values:

| Type | First Argument | Second Argument | Return Value |

|---|---|---|---|

u8 / i8

|

A register | L register | A register |

u16 / i16

|

HL register pair | DE register pair | HL register pair |

Additional arguments go on the stack. The stack frame uses the IX register as a frame pointer when needed. This convention minimizes register shuffling for common cases — a function taking two 16-bit arguments and returning one uses HL and DE for input and HL for output, requiring no setup at all.

This differs from traditional Z80 calling conventions used by C compilers, which typically pass all arguments on the stack. Our approach is more register-heavy, which suits the short functions typical of embedded code.

Practical Implications

Let me be clear about what we've achieved and what remains out of reach.

What you can realistically build:

- Simple embedded routines: LED patterns, sensor reading, basic I/O handling

- Mathematical functions: integer arithmetic, lookup tables, state machines

- Protocol handlers: parsing simple data formats, generating responses

- Anything that would fit in a few kilobytes of hand-written assembly

What you cannot build:

- Anything requiring heap allocation: no

Vec, noString, no dynamic data structures - Code using iterators or closures: these generate complex LLVM IR that overwhelms the register allocator

- Formatted output: Rust's

write!macro and formatting infrastructure are far too heavy - Floating-point calculations: not without significant backend work

The path to making this more capable is visible but non-trivial. A custom minimal core implementation that avoids floating-point entirely would help. Improving the register allocator's handling of phi nodes would enable loops. Adding software floating-point legalization would unlock numerical code. Each of these is a substantial project.

Reflections

Building a compiler backend for a 50-year-old processor using a 21st-century language toolchain is an exercise in contrasts. Modern software assumes abundant resources. The Z80 was designed when resources were precious. Making them meet requires translation across decades of computing evolution.

The fact that we needed 252GB of RAM to compile code for a processor with a 64KB address space is almost poetic. It captures something essential about how far computing has come and how much we've traded simplicity for capability.

But here's what satisfies me: the generated Z80 code is good. It's not bloated or obviously inefficient. When we compile a simple function, we get a simple result. The LLVM optimization passes do their job, and our backend translates the result into idiomatic Z80 assembly. The 'l' character optimization in our Hello World example isn't something I would have thought to do by hand, but the compiler found it automatically.

Rust on Z80 isn't practical for production use. The core library is too heavy, the workarounds are too fragile, and the resulting code size would exceed most Z80 systems' capacity. But as a demonstration that modern toolchains can target ancient hardware? As an exploration of what compilers actually do? As an answer to "I wonder if this is possible?"

Yes. It's possible. And the journey to get here taught me more about LLVM, register allocation, and instruction selection than any tutorial ever could.

What's Next

With emulation working, the obvious next step is running this code on actual hardware. My RetroShield Z80 sits waiting on my workbench, ready to execute whatever binary we load into it. The emulator uses the same ACIA interface as the physical hardware, so the transition should be straightforward — load the binary, connect a terminal, and watch "Hello, Z80 World!" appear on genuine 8-bit silicon.

Beyond hardware validation, the Z80 backend needs work on loop handling. Phi nodes are the enemy. There may be ways to lower them earlier in the pipeline, before they reach the register-hungry instruction selector. That's a project for another day, another blog post, and probably another round of pair programming with Claude.

The projects are available on GitHub for anyone curious enough to try them:

- LLVM with Z80 backend: github.com/ajokela/llvm-z80

-

Rust with Z80 target: github.com/ajokela/rust-z80 (see the

z80-backendbranch) - Z80 Emulator: github.com/ajokela/retro-z80-emulator

Be warned: you'll need more RAM than seems reasonable. But if you've read this far, you probably already suspected that.

Resources

If you want to dive deeper into any of the topics covered here, these resources might help:

Books:

- Programming the Z80 by Rodnay Zaks — The definitive Z80 reference, covering every instruction and addressing mode in detail

-

The Rust Programming Language by Klabnik and Nichols — The official Rust book, essential for understanding

no_stdembedded development - Engineering a Compiler by Cooper and Torczon — Comprehensive compiler textbook covering instruction selection, register allocation, and code generation

- Crafting Interpreters by Robert Nystrom — Excellent practical guide to building language implementations

Hardware:

- Z80 CPU chips — Original Zilog Z80 processors, still available new and vintage

- RetroShield Z80 — Arduino shield that lets you run a real Z80 with modern conveniences

- USB to Serial adapters — Essential for connecting to vintage hardware

- Logic Analyzer — Invaluable for debugging Z80 bus timing and signals