The Pitch

Every few years, a new programming language appears that promises to fix what its predecessors got wrong. Most quietly vanish. A handful become infrastructure. What makes Rue interesting is not that it promises to replace Rust—its creator explicitly says it won't—but that the person making it is one of the most qualified people alive to attempt the experiment.

Steve Klabnik spent thirteen years in the Rust ecosystem. He co-authored The Rust Programming Language, the official book that has introduced more people to Rust than any other resource. He served on the Rust core team, led its documentation team, and worked at Mozilla during Rust's formative years. He later joined Oxide Computer Company, where he contributed to a scratch-built operating system written in Rust. Before all of that, he was a prolific contributor to Ruby on Rails and authored Rust for Rubyists, one of the earliest attempts to bridge the Ruby and Rust communities.

If anyone has earned the right to look at Rust and say "I think we can do this differently," it's Klabnik. And that's exactly what Rue is: a research project asking whether memory safety without garbage collection can be achieved with less cognitive overhead than Rust demands.

But Rue is also something else entirely—an experiment in whether a single person, assisted by an AI, can build a programming language from scratch without funding, without a team, and without a multi-year timeline. The compiler is written in Rust, designed by Klabnik, and implemented primarily by Claude, Anthropic's AI assistant. The project went from nothing to a working compiler in roughly two weeks, producing approximately 100,000 lines of Rust code across 700+ commits.

The Person Behind It

Understanding Rue requires understanding Klabnik's trajectory through programming language communities. He entered professional programming through Ruby, becoming one of the most prolific open-source contributors to the Rails ecosystem in the early 2010s. His final commits to Rails landed in late 2013, around the time he discovered Rust 0.5 during a Christmas visit to his parents' house in rural Pennsylvania.

What followed was a thirteen-year involvement with Rust that few can match. Beyond the official book (now in its second edition, co-authored with Carol Nichols and published by No Starch Press), Klabnik shaped how the Rust community communicates, documents, and teaches. His work on Rust's documentation established patterns that other language communities later adopted. At Mozilla, he helped shepherd Rust through its 1.0 release. At Oxide, he worked on systems software at the lowest levels the language supports.

Klabnik describes himself as having been an AI skeptic until 2025, when he found that large language models had crossed a threshold of genuine usefulness for programming. The shift was dramatic enough that he now writes most of his code with AI assistance. Rue is the product of that conversion—not just a language experiment but a methodology experiment, testing what happens when a deeply experienced language designer directs an AI to implement his vision.

The name follows a deliberate pattern from his career: Ruby, Rust, Rue. He notes three associations—"rue the day" (the negative connotation, a nod to the skepticism any new language faces), the rue plant (paralleling Rust's fungal connotation), and brevity.

What Rue Is Today

Let's be direct about the current state: Rue is a version 0.1.0 research project. The website prominently warns that it is "not ready for real use" and to "expect bugs, missing features, and breaking changes." Klabnik himself has described the language as "still very janky" and cautions against reading too deeply into current implementation details. The GitHub README puts it plainly: "Not everything in here is good, or accurate, or anything: I'm just messing around."

With that caveat firmly in place, here's what exists.

Rue compiles to native machine code targeting x86-64 and ARM64. There is no virtual machine, no interpreter, and no garbage collector. The compiler is written in Rust (95.8% of the repository) and produces binaries directly. It builds using Buck2, Meta's build system, and the project includes a specification, a ten-chapter tutorial, a blog, and a benchmark dashboard that tracks compilation time, memory usage, and binary size across Linux and macOS.

The language itself is statically typed with type inference. Variables are declared with let (immutable by default) or let mut (mutable), following Rust's convention. The type system includes signed and unsigned integers (i8 through i64, u8 through u64), booleans, fixed-size arrays, structs, and enums. There are no strings. There is no standard library. There are no traits, no closures, no iterators, no modules, no error handling beyond panics, and no heap allocation. Generics exist behind a --preview comptime flag—more on that below—but they are not yet part of the stable language.

Read that list of absences again. It is long. And it is honest.

The Type System and Memory Model

Rue's central technical bet is that affine types with mutable value semantics can deliver memory safety more intuitively than Rust's borrow checker and lifetime annotations.

In practice, this means values in Rue are moved by default. When you assign a struct to a new variable or pass it to a function, the original becomes invalid—the compiler enforces single ownership at the type level. This is Rust's move semantics without the escape hatches that references and borrowing provide. If you want a type to be copied instead of moved, you annotate the struct definition with @copy, which enables value duplication.

Where Rust provides shared references (&T) and mutable references (&mut T) governed by the borrow checker's aliasing rules, Rue provides two simpler mechanisms: borrow and inout.

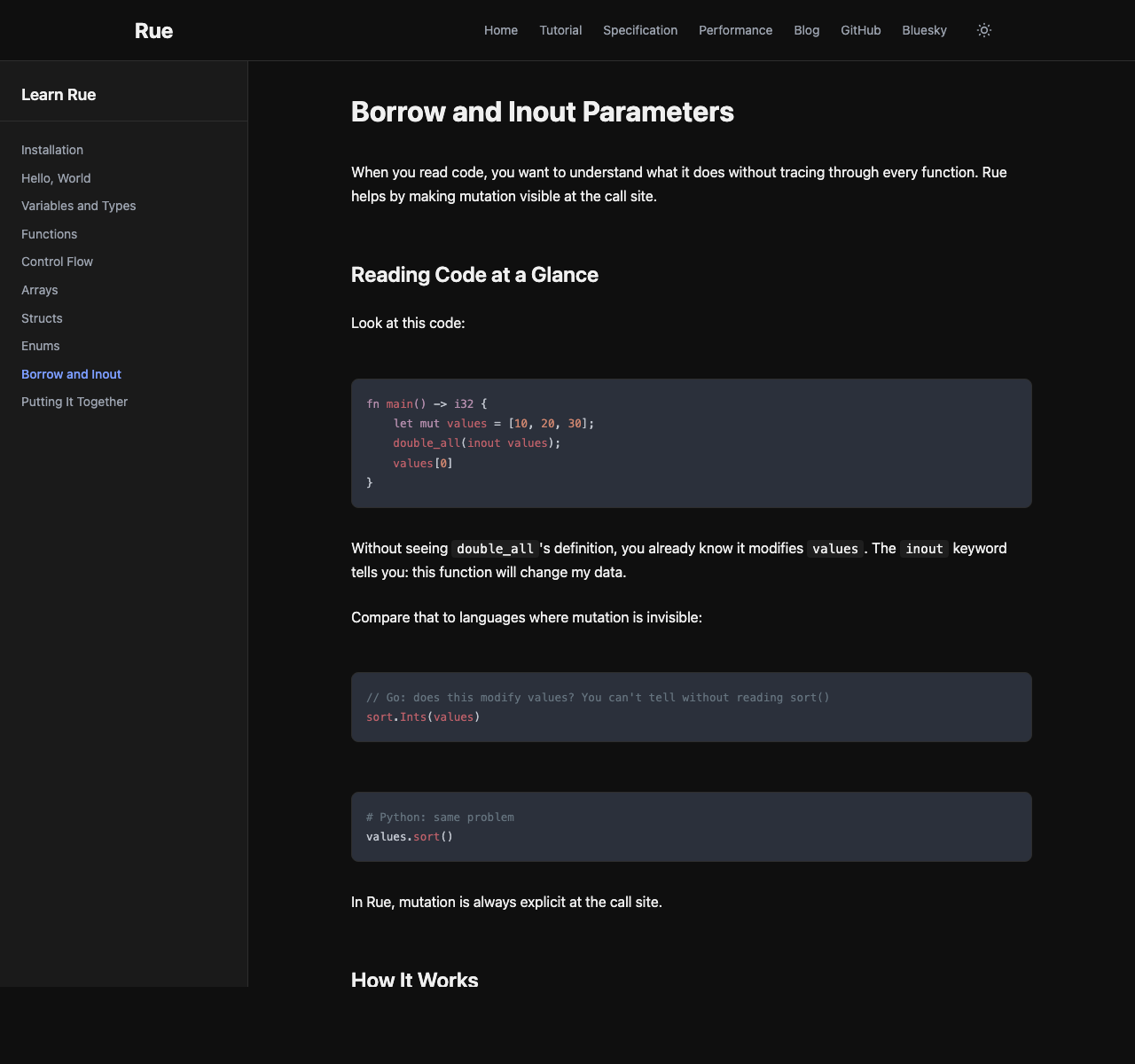

A borrow parameter grants read-only access to a value without copying it. An inout parameter grants temporary mutable access—the function can modify the value, and changes persist after the function returns. Critically, both are marked at the call site, not just in the function signature. When reading Rue code, you can immediately see which arguments a function will modify:

sort(inout values, borrow config);

The tutorial makes the design motivation explicit: "When you read code, you want to understand what it does without tracing through every function." In Go or Python, a function receiving a slice or object might mutate it invisibly. In Rue, mutation is always syntactically visible where the function is called.

This is genuinely appealing. One of Rust's persistent pain points is that understanding what a function does to its arguments requires reading the signature carefully—and even then, interior mutability patterns like RefCell can make the signature misleading. Rue's approach trades expressiveness for legibility.

The trade-off, however, is severe. Without general references, you cannot build self-referential data structures. Linked lists, trees, and graphs—the bread and butter of systems programming data structures—have no obvious implementation path in current Rue. The Hacker News discussion around the language's announcement surfaced this concern immediately: without references that can be stored in data structures, you cannot implement iterators that borrow from containers. This is not a missing feature that will be added later; it is a fundamental consequence of the design choice.

Klabnik has acknowledged this directly: "There is going to inherently be some expressiveness loss. There is no silver bullet." The question Rue poses is whether the expressiveness that remains is sufficient for a useful class of programs. The answer today is: we don't know yet.

What the Tutorial Reveals

The ten-chapter tutorial walks from installation through a capstone quicksort implementation. It covers variables, types, functions, control flow, arrays, structs, enums, and the borrow/inout system. The final chapter implements partitioning and recursive sorting, demonstrating how the language's features compose.

Working through it reveals a language that feels like a simplified Rust with the hard parts surgically removed. Pattern matching on enums is exhaustive, as in Rust. Structs have named fields and move semantics. Arrays are fixed-size with runtime bounds checking that panics on out-of-bounds access. Integers overflow-check by default.

The syntax is deliberately familiar to anyone who has written Rust, Go, or C. Function signatures look like Rust without lifetimes:

fn partition(arr: inout [i32; 5], low: u64, high: u64) -> u64

Control flow uses if/else and while without parentheses around conditions. There is no for loop—iteration requires manual index management with while, which feels like a notable omission even for an early-stage language.

What's conspicuously absent from the tutorial is any program that does something useful beyond computation. There is no file I/O, no string handling, no network access, no memory allocation. The only output mechanism is @dbg(), a built-in debug print. The actual hello.rue in the examples directory is revealing: it is fn main() -> i32 { 42 }. There are no strings, so there is no "Hello, World." The fizzbuzz example is equally telling—it returns integers (1 for Fizz, 2 for Buzz, 3 for FizzBuzz) because it cannot print the words. The specification explicitly excludes coverage of a standard library "when one exists."

The AI Development Story

The most widely discussed aspect of Rue is not its type system but how it was built. Klabnik's blog posts describe a process where he provided architectural direction and design decisions while Claude wrote the vast majority of the implementation code. The project's blog posts are co-credited to both Klabnik and Claude, with some posts authored solely by the AI.

The timeline is striking. The first commit landed on December 15, 2025. By December 22—one week later—the compiler could handle basic types, structs, control flow, and had accumulated 130 commits. By early January 2026, the project had 777 specification tests across two platforms and the compiler had grown to handle enums, pattern matching, arrays, and the borrow/inout system.

The repository now contains over 700 commits from 4 contributors, with 1,100+ GitHub stars. For a personal hobby project by a well-known developer, this represents meaningful interest—though not the kind of momentum that suggests organic community adoption.

This development model raises legitimate questions. When Claude writes the compiler and Claude writes the blog posts, what does it mean for a human to have "designed" the language? Klabnik's answer is that he makes all architectural and design decisions—what features to include, how the type system works, what trade-offs to accept—while the AI handles implementation. He compares it to an architect and a construction crew: the architect doesn't lay bricks, but the building reflects the architect's vision.

The analogy is imperfect. A construction crew doesn't suggest design changes mid-build based on patterns learned from every other building ever constructed. But the broader point—that directing implementation is itself a form of authorship—is reasonable, and Klabnik's thirteen years of language implementation experience give him credibility that a less experienced designer directing an AI would lack.

What the Source Code Reveals

The documentation and tutorial tell one story. The GitHub repository tells a more nuanced one. Digging into the examples directory and compiler crates reveals features in various stages of development that the official tutorial has not yet caught up with.

Most notably, generics exist as a preview feature. The examples/generics.rue file demonstrates Zig-style comptime type parameters:

fn max(comptime T: type, a: T, b: T) -> T { if a > b { a } else { b } } let bigger = max(i32, 10, 20);

The comptime T: type syntax tells the compiler to monomorphize—creating specialized versions (max__i32, max__bool, etc.) for each concrete type used at call sites. This is a meaningful step beyond what the tutorial covers, and it follows the Zig model rather than Rust's trait-bounded generics. Whether this approach will scale to real-world code—and whether it can support the kind of type-level abstraction that traits and interfaces provide—remains to be seen. You must compile with rue --preview comptime to access this feature, signaling that it is experimental even by Rue's standards.

The compiler architecture itself is surprisingly mature for a project of this age. The repository contains 18 separate crates: a lexer, parser, intermediate representation (rue-rir), an abstract intermediate representation (rue-air), control flow graph analysis (rue-cfg), code generation, linking, a fuzzer, a spec test runner, and a VS Code extension. This is not a toy single-file compiler—it is a modular pipeline that reflects real compiler engineering, even if the language it compiles remains minimal.

Beyond generics, the gaps are still significant. There are no traits or interfaces, so there is no polymorphism beyond what enums and comptime monomorphization provide. There are no closures or first-class functions. There is no error handling mechanism—functions can panic, but there is no Result type or equivalent. There are no modules or visibility controls. There are no methods on types. There is no string type.

The unchecked keyword provides an escape hatch similar to Rust's unsafe, allowing low-level memory operations while keeping such code "visibly separate from normal safe code." The specification includes chapters on unchecked code syntax and unchecked intrinsics, suggesting that Klabnik recognizes the eventual need for the kind of low-level access that Rust provides through its unsafe system.

The performance page tracks compilation metrics—time, memory, binary size—across x86-64 and ARM64 on both Linux and macOS, but provides no runtime benchmarks comparing Rue's generated code to C, Rust, or Go. This is understandable for a research project, but it means we cannot evaluate whether Rue's native compilation delivers competitive performance.

The Fundamental Question

Every new systems language must answer the same question: what programs can I write in this language that I couldn't write (or couldn't write as well) in an existing one?

For Rust, the answer was clear from early on: memory-safe systems programs without garbage collection pauses. For Go, it was concurrent network services with fast compilation. For Zig, it was a C replacement with better defaults and comptime.

Rue's answer, as it stands today, is: nothing. Not yet. You cannot write a program in Rue that you couldn't write more easily in any mainstream language, because Rue cannot perform I/O, allocate memory, manipulate strings, or interact with the operating system.

This is not a criticism so much as a statement of development stage. The interesting question is what Rue's answer could become if development continues. The borrow/inout model is genuinely simpler than Rust's borrow checker for the cases it handles. Generics are already emerging through the comptime preview. If Rue can stabilize them, grow a heap allocator, a string type, and enough standard library to write real programs—without reintroducing the complexity it was designed to avoid—it could serve programmers who find Rust's learning curve prohibitive but need more safety than C or Go provide.

That is a big "if." History is littered with languages that simplified an existing language's hard parts and then discovered that the hard parts existed for good reasons. Rust's borrow checker is complex because the problems it solves are complex. Removing it and replacing it with a simpler system necessarily means either accepting less expressiveness or finding a genuinely novel solution that the Rust team somehow missed in over a decade of research.

Klabnik is explicit that he doesn't claim to have found such a solution. Rue is a research project exploring a design space, not a product claiming to have mapped it.

Who Should Pay Attention

If you're looking for a language to write software in today, Rue is not it. The project's own documentation says so clearly and repeatedly.

If you're interested in programming language design, Rue is worth following for two reasons. First, the borrow/inout model is a clean articulation of an alternative to Rust's reference system, and watching it encounter real-world requirements will be educational regardless of whether it succeeds. Second, the AI-assisted development methodology is itself a data point in the ongoing question of what role AI can play in building complex software systems.

If you're a Rust programmer who has ever thought "there must be a simpler way to express this," Rue represents one concrete exploration of what "simpler" might look like—and what it costs. The language makes the trade-offs visible in a way that abstract arguments about borrow checker complexity do not.

And if you're Steve Klabnik, messing around with a hobby project after thirteen years of working on someone else's language, Rue looks like exactly the kind of thing a deeply experienced language person should be doing with their evenings and weekends.

Conclusion

Rue is best understood as three things simultaneously: a technical experiment in memory safety ergonomics, a methodological experiment in AI-assisted language development, and a personal project by someone with unusually deep expertise in the problem space. As a technical experiment, it has articulated a clean alternative to Rust's borrow checker that is worth studying even if it proves too restrictive for general use. As a methodological experiment, the speed of development—700+ commits and a working multi-platform compiler in weeks—is genuinely remarkable, though the long-term maintainability of AI-generated compiler code remains unproven. As a personal project, it is honest about its limitations in a way that many language announcements are not.

The language cannot do anything useful yet. It may never be able to. But the questions it asks—can memory safety be simpler? can one person with an AI build a compiler? what happens when you remove the borrow checker and try something else?—are worth asking. And the person asking them has spent over a decade earning the credibility to make the attempt interesting rather than naive.

Watch the GitHub repository. Read the specification. Try the tutorial if you're curious about what a post-Rust systems language might feel like. Just don't write anything important in it yet.