Introduction

There is a particular category of programming book that transcends its subject matter, becoming not just a reference but an experience. Crafting Interpreters by Robert Nystrom belongs firmly in this category. Originally published in 2021 after six years of development, the book tackles what many programmers consider one of the most intimidating topics in computer science—building a programming language from scratch—and makes it not just accessible but genuinely enjoyable.

Nystrom is no stranger to technical writing that connects with practitioners. His earlier book Game Programming Patterns demonstrated a talent for explaining complex software concepts through clear prose and practical examples. With Crafting Interpreters, he applies that same skill to language implementation, a domain traditionally guarded by dense academic texts and formal notation that sends most working programmers running.

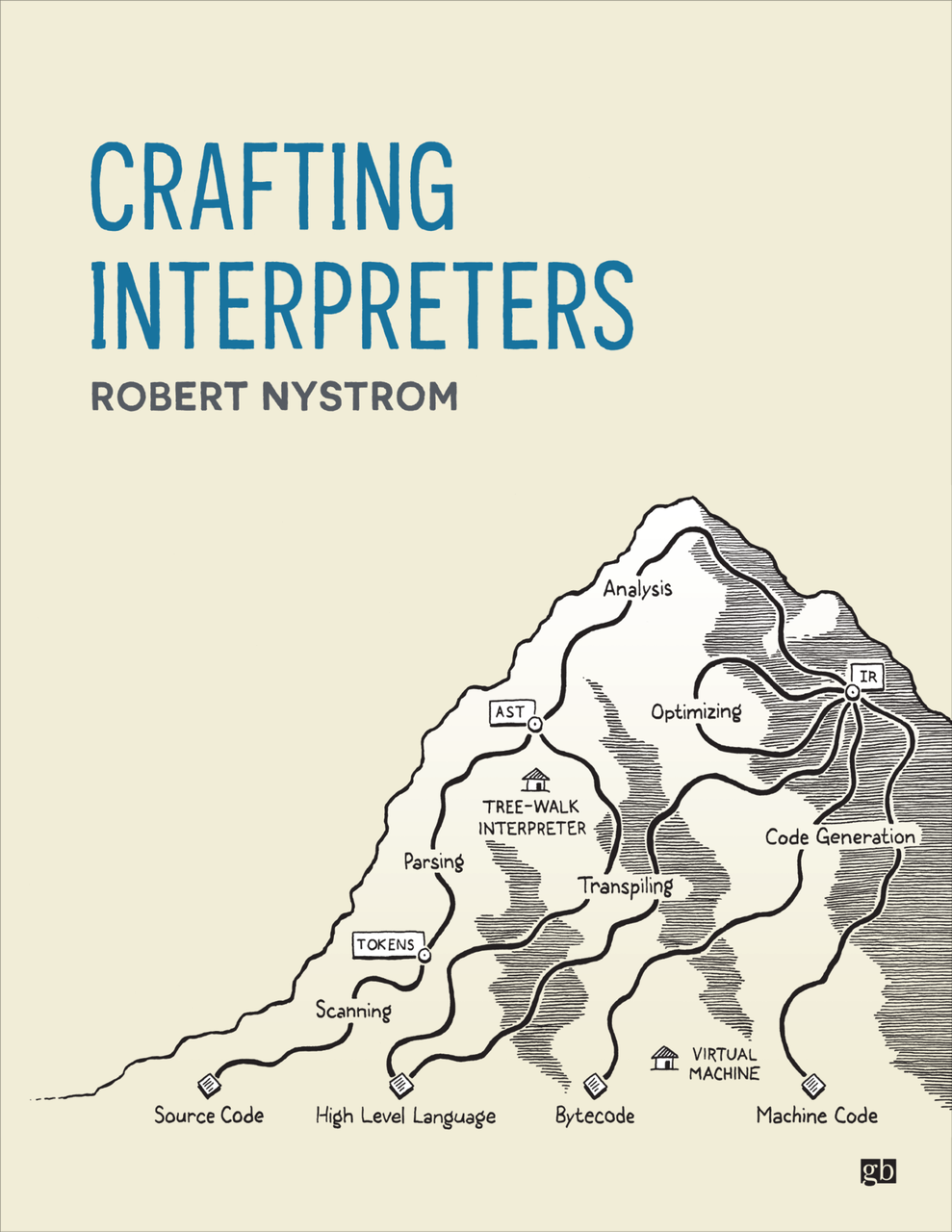

The book's central premise is both ambitious and elegant: build the same programming language twice. First as a tree-walk interpreter in Java (called jlox), then as a bytecode virtual machine in C (called clox). This dual implementation strategy isn't just a structural gimmick. It serves a deep pedagogical purpose, allowing readers to first grasp the conceptual architecture of language processing in a high-level language before rebuilding everything from raw memory and pointer arithmetic. The result is a book that manages to teach compiler theory, language design, software architecture, and low-level systems programming simultaneously.

The entire text is freely available at craftinginterpreters.com, which speaks to Nystrom's commitment to making this knowledge widely accessible. The physical edition, published with care and featuring hand-drawn illustrations throughout, is worth owning for anyone who works through the material.

The Language: Lox

Before diving into implementation, Nystrom introduces Lox, the language both interpreters will execute. Lox is a dynamically typed, garbage-collected language with C-family syntax that supports first-class functions, closures, and class-based object orientation with single inheritance. It is deliberately modest in scope—no arrays, no module system, no standard library to speak of—but this restraint is precisely the point.

Every feature in Lox exists because it teaches something important about language implementation. Dynamic typing means building a runtime type system. Garbage collection means understanding memory management at the deepest level. Closures require wrestling with variable capture and lifetime semantics. Classes and inheritance demand method resolution and the vtable-like dispatch mechanisms that underpin most object-oriented languages. Lox is small enough to implement in a book but complex enough that implementing it forces the reader to confront every major challenge in language design.

The choice of a custom language rather than a subset of an existing one is significant. It frees Nystrom from having to explain why certain features are omitted or work differently than readers might expect. Lox is exactly what it needs to be, nothing more.

Part II: The Tree-Walk Interpreter (jlox)

The first implementation spans thirteen chapters and builds a complete interpreter in Java. Nystrom begins where every language implementation must—with scanning. The scanner chapter walks through converting raw source text into tokens, handling string literals, numbers, keywords, and the inevitable edge cases that make lexical analysis more interesting than it first appears.

From there, the book moves into parsing, where Nystrom introduces recursive descent parsing with a clarity that makes the technique feel almost obvious in hindsight. Rather than reaching for parser generators like YACC or ANTLR, every line of the parser is written by hand. This decision is characteristic of the book's philosophy: no black boxes, no magic, no dependencies. The reader understands every piece because the reader built every piece.

The chapters on expression evaluation and statement execution establish the runtime model, but the book truly hits its stride in the chapters on scope and environments. Nystrom's explanation of lexical scoping—using a chain of environment objects that form what he calls a "cactus stack"—is one of the clearest treatments of this topic in any programming text. The hand-drawn illustration of nested environments, with their parent pointers threading back through enclosing scopes, communicates in a single image what paragraphs of formal specification struggle to convey.

Functions and closures represent the first major conceptual challenge, and Nystrom handles them with characteristic patience. The problem of captured variables—where a closure must hold onto variables from an enclosing scope that may have already returned—is presented as a puzzle to be solved rather than a rule to be memorized. The resolver pass that performs static analysis to determine variable binding is introduced as a natural response to a concrete bug, not as an abstract compiler phase.

The object-oriented chapters add classes, methods, constructors, inheritance, and super expressions. By the time jlox is complete, the reader has built a language implementation capable of running recursive algorithms, managing object hierarchies, and handling the scoping rules that trip up even experienced programmers in production languages.

What makes this section exceptional is Nystrom's willingness to show the design process, not just the final design. When a naive approach creates a bug or performance problem, the reader sees it happen and participates in fixing it. This iterative development style mirrors how real software is built and teaches debugging intuition alongside language implementation.

Part III: The Bytecode Virtual Machine (clox)

If Part II is the approachable on-ramp, Part III is where the book reveals its true ambition. Across seventeen chapters, Nystrom rebuilds everything in C, this time compiling Lox to bytecode and executing it on a stack-based virtual machine. The motivation is made concrete early: jlox takes 72 seconds to compute the 40th Fibonacci number recursively, while C can do it in half a second. The bytecode VM will close that gap dramatically.

The transition from Java to C is itself educational. Readers who have grown comfortable with Java's automatic memory management, dynamic arrays, and hash maps must now implement all of these from scratch. Nystrom builds a dynamic array type, a hash table, and ultimately a mark-sweep garbage collector, all in service of the language implementation. These data structures are not taught in isolation—they emerge because the VM needs them.

The chunk and instruction design chapters teach the reader to think about data representation at the byte level. Each bytecode instruction is a single byte, followed by operands that encode constants, variable slots, or jump offsets. The disassembler that Nystrom builds alongside the VM is a thoughtful touch, providing a debugging tool that makes the otherwise invisible bytecode tangible.

The single-pass compiler that replaces jlox's separate parsing and resolution phases is a masterclass in practical compiler construction. Nystrom uses Pratt parsing for expressions—a technique he explains with such clarity that this chapter alone has become a widely referenced resource for anyone implementing expression parsers. The Pratt parser's elegant handling of precedence and associativity through a simple table of parsing functions is one of those ideas that, once understood, feels like it should have been obvious all along.

The chapters on closures in clox deserve special mention. Where jlox could lean on Java's garbage collector and object references to capture variables, clox must solve the "upvalue" problem explicitly. Nystrom introduces the concept of upvalues—runtime objects that represent captured variables—and walks through the mechanism by which stack-allocated locals are "closed over" and moved to the heap when their enclosing function returns. The complexity of this implementation, managed through careful incremental development, demonstrates why closures are considered one of the hardest features to implement correctly in a bytecode VM.

The garbage collection chapter is the book's peak of systems programming depth. Nystrom implements a mark-sweep collector, explaining reachability, root sets, and the tricolor abstraction. The treatment is practical rather than theoretical—the reader sees exactly when collection triggers, how objects are traced, and why the collector must handle the subtle case of the VM itself allocating memory during collection (which could invalidate pointers being traced). The self-adjusting heap threshold that balances collection frequency against memory usage is a detail that separates a textbook GC from one that works in practice.

Writing Style and Presentation

Nystrom's prose is the book's secret weapon. Technical writing about compilers tends toward one of two failure modes: impenetrable formalism or hand-waving oversimplification. Nystrom avoids both. His writing is conversational without being sloppy, precise without being dry. Footnotes contain genuine wit. Asides acknowledge the reader's likely confusion at exactly the moments when confusion is most natural.

The hand-drawn illustrations scattered throughout the book serve a purpose beyond aesthetics. They signal that this is a personal, crafted work rather than a mass-produced textbook. The diagrams of memory layouts, parse trees, and stack states during execution are clearer than their machine-generated equivalents in most compiler texts, partly because they include exactly the detail needed and nothing more.

The "Design Note" sections that appear between chapters are mini-essays on language design philosophy—why dynamic typing exists, what makes a feature "elegant," how language designers balance expressiveness against implementation complexity. These sections transform the book from a pure implementation guide into something closer to a meditation on programming language design as a creative discipline.

Strengths

The book's greatest achievement is making compiler construction feel like a natural extension of everyday programming rather than a specialized academic pursuit. By avoiding formal grammars, automata theory, and the mathematical notation that dominates traditional compiler texts, Nystrom demonstrates that you don't need a PhD to build a working language implementation.

The dual-implementation approach pays dividends throughout. Concepts that are murky in one implementation become clear in the other. The tree-walk interpreter makes the abstract concepts tangible; the bytecode VM reveals the performance and engineering considerations that production language implementations face. Together, they provide a stereoscopic view of language implementation that neither could achieve alone.

The no-dependency philosophy deserves praise. There is no lexer generator, no parser generator, no framework, no library. Every line of code in both implementations is written in the book and understood by the reader. This means that upon completion, the reader owns their understanding completely—there is no mysterious tool doing critical work behind the scenes.

The incremental development style produces a book that is remarkably difficult to get lost in. Each chapter begins with working code and ends with working code. The reader is never more than a few pages from being able to compile and run something. For a topic as complex as language implementation, this steady cadence of progress is essential for maintaining motivation.

Limitations

The book is not without its shortcomings. The choice of dynamic typing for Lox means that static type systems—one of the most active and important areas of modern language design—receive no coverage. Type inference, generics, algebraic data types, and pattern matching are absent. A reader completing both implementations still would not know how to add a type checker, which is arguably the most practically relevant compiler phase for working programmers today.

Optimization is largely unexplored. The clox VM is faster than jlox by virtue of being a bytecode interpreter written in C, but Nystrom does not cover constant folding, dead code elimination, register allocation, or any of the optimization passes that distinguish a teaching compiler from a production one. JIT compilation, increasingly the standard for high-performance language runtimes, is mentioned only in passing.

The error handling and recovery throughout both implementations is minimal. Production parsers need sophisticated error recovery to provide useful diagnostics. Nystrom acknowledges this gap but does not address it, leaving readers who want to build user-facing tools with significant work ahead of them.

Lox's deliberate simplicity means that several common language features—arrays, iterators, modules, pattern matching, exception handling—are left as exercises. While this keeps the book focused, it means that readers must figure out on their own how to implement the features that most real languages require. The gap between Lox and a practical language is significant.

Who Should Read This Book

Crafting Interpreters is ideal for working programmers who have always been curious about how languages work but have been intimidated by the traditional compiler literature. Comfortable familiarity with Java and C is assumed—this is not a book for learning either language. But the reader need not have any prior knowledge of compilers, formal languages, or automata theory.

Computer science students will find it an excellent companion to a formal compilers course, providing the practical intuition that textbooks like Aho's Dragon Book deliberately omit. Conversely, self-taught programmers who never took a compilers course will find this book fills a significant gap in their education.

Language enthusiasts who have tinkered with toy interpreters but never built anything with closures, classes, or garbage collection will find exactly the guidance they need to level up. And anyone who simply enjoys beautifully crafted technical writing will find the book rewarding even as a pure reading experience.

Conclusion

Crafting Interpreters is one of the best programming books published in recent years. It takes a subject that most programmers consider forbiddingly complex and renders it not just comprehensible but engaging. Nystrom's combination of clear writing, thoughtful pedagogy, practical focus, and genuine craft produces a book that teaches far more than its nominal subject. Beyond scanning, parsing, and code generation, the reader learns how to approach complex software design, how to build systems incrementally, and how to think about the tools they use every day at a deeper level.

The book will not make you a compiler engineer. It will not teach you how to build a production language runtime, optimize generated code, or implement a sophisticated type system. What it will do is demystify the machinery that powers every programming language you have ever used, and give you the confidence and foundation to explore further. For most programmers, that is more than enough. It is, in fact, exactly what was needed.