Most programming languages treat mutability as a binary property. A variable is either mutable or it's not. You declare it one way, and that's the end of the story. Rust adds nuance with its ownership and borrowing model, and functional languages sidestep the question by making everything immutable by default, but the fundamental framing remains the same: mutability is a static attribute decided at declaration time.

Lattice takes a different approach. In Lattice, mutability is a phase — a state that a value passes through over its lifetime, like matter transitioning between liquid and solid. A value starts as mutable flux, and when you're done shaping it, you freeze it into immutable fix. Need to modify it again? Thaw it back to flux. Want to build something complex and immutable in one shot? Use a forge block — a controlled mutation zone whose output automatically crystallizes.

This isn't just a metaphor. The phase system is woven through Lattice's entire runtime, from its type representation to its memory management architecture. This post is a deep dive into what that means, how it works at the implementation level, and why it represents a genuinely different way of thinking about the relationship between mutability and memory.

The Problem Lattice Solves

Every language designer eventually confronts the same tension: programmers need mutability to build things, but mutability is the source of most bugs. Shared mutable state causes race conditions. Unexpected mutation causes aliasing bugs. Mutable references that outlive their owners cause use-after-free errors.

Different languages resolve this tension in different ways, and each approach carries trade-offs.

Garbage-collected languages (Java, Python, Go, JavaScript) let you mutate freely and use a garbage collector to clean up. This is convenient but pushes the cost to runtime — GC pauses, unpredictable memory usage, and no compile-time guarantees about who can modify what. You gain ease of use but lose control.

Rust's ownership model provides compile-time guarantees through a sophisticated borrow checker. You can have either one mutable reference or many immutable references, but not both. This eliminates data races at compile time, but the cost is complexity — the borrow checker is notoriously difficult for newcomers, lifetime annotations add syntactic weight, and certain patterns (like self-referential structs or graph structures) require unsafe escape hatches.

Functional languages (Haskell, Erlang, Clojure) default to immutability and model mutation through controlled mechanisms like monads, processes, or atoms. This produces correct programs but can feel unnatural for inherently stateful problems, and persistent data structures carry performance overhead.

C and C++ give you full manual control and zero overhead, at the cost of memory safety. const in C is advisory at best — you can cast it away, and the compiler won't stop you from freeing memory that someone else is still using.

Lattice's phase system is an attempt to find a different point in this design space. The core insight is that in most programs, values have a natural lifecycle: they're constructed (requiring mutation), then used (requiring stability), and occasionally reconstructed (requiring mutation again). The phase system makes this lifecycle explicit and enforceable.

The Phase Model

Lattice has three binding keywords that correspond to mutability phases:

flux declares a mutable binding. A flux variable can be reassigned, and its contents can be modified in place. This is where you do your work — building arrays, populating maps, incrementing counters.

flux counter = 0 counter += 1 counter += 1

fix declares an immutable binding. A fix variable cannot be reassigned, and its contents cannot be modified. Attempting to mutate a fix binding is an error.

fix pi = freeze(3.14159) // pi = 2.0 -- error: cannot assign to crystal binding

let is the inferred form (available in casual mode). It doesn't enforce a phase — the value keeps whatever phase tag it already has.

The transitions between phases are explicit function calls:

-

freeze(value)transitions a value from fluid to crystal. In strict mode, this is a consuming operation — the original binding is removed from the environment. You can't accidentally keep a mutable reference to something you've declared immutable. -

thaw(value)creates a mutable deep clone of a crystal value. The original remains frozen; you get a completely independent mutable copy. -

clone(value)creates a deep copy without changing phase.

And then there's the forge block, which is perhaps the most interesting construct:

fix config = forge {

flux temp = Map::new()

temp.set("host", "localhost")

temp.set("port", "8080")

temp.set("debug", "true")

freeze(temp)

}

A forge block is a scoped computation whose result is automatically frozen. Inside the forge, you can use flux variables and mutate freely. But whatever value the block produces comes out crystallized. The temporary mutable state is gone — only the finished, immutable result survives.

This addresses a real pain point. In functional languages, building a complex immutable data structure often requires awkward chains of constructor calls or builder patterns. In Lattice, you just... build it, mutably, in a forge block, and it comes out frozen. The forge acknowledges that construction is inherently a mutable process, while insisting that the result of construction should be stable.

Under the Hood: How the Phase System Maps to Memory

Lattice is implemented as a tree-walking interpreter in C — roughly 6,000 lines across the lexer, parser, phase checker, and evaluator. The implementation reveals some interesting design decisions about how phase semantics interact with memory management.

Value Representation

Every runtime value in Lattice is a LatValue struct — a tagged union carrying a type tag, a phase tag, and the value payload:

struct LatValue { ValueType type; // VAL_INT, VAL_STR, VAL_ARRAY, VAL_MAP, ... PhaseTag phase; // VTAG_FLUID, VTAG_CRYSTAL, VTAG_UNPHASED union { ... } as; };

Primitive values (integers, floats, booleans) live inline in the union — no heap allocation. Compound values (strings, arrays, structs, maps, closures) own heap-allocated payloads. A string holds a heap-allocated character buffer. An array holds a malloc'd element buffer. A map holds a pointer to an open-addressing hash table.

Deep-Clone-on-Read: Value Semantics Without a Compiler

The most consequential design decision in Lattice's runtime is that every variable read produces a deep clone. When you access a variable, the environment doesn't hand you a reference to the stored value — it hands you a complete, independent copy.

bool env_get(const Env *env, const char *name, LatValue *out) { for (size_t i = env->count; i > 0; i--) { LatValue *v = lat_map_get(&env->scopes[i-1], name); if (v) { *out = value_deep_clone(v); // always a fresh copy return true; } } return false; }

This is expensive. Every array access clones the entire array. Every map read clones every key-value pair. But it eliminates an entire class of bugs. There is no aliasing in Lattice. Two variables never point to the same underlying memory. When you pass a map to a function, the function gets its own copy — mutations inside the function don't leak back to the caller. When you assign an array to a new variable, you get two independent arrays.

This is the implementation strategy that makes Lattice's maps value types. In most languages, objects and collections are reference types — assigning them to a new variable creates a new reference to the same data. In Lattice, assignment means duplication. This is closer to how values work in mathematics than how they work in most programming languages.

For in-place mutation within a scope (like array.push() or map.set()), Lattice uses a separate resolve_lvalue() mechanism that obtains a direct mutable pointer into the environment's storage, bypassing the deep clone. This means local mutations are efficient — it's only cross-scope communication that pays the cloning cost.

The Dual Heap Architecture

Lattice's memory subsystem uses what the implementation calls a DualHeap — two separate allocation regions with different management strategies:

The FluidHeap manages mutable data using a mark-and-sweep garbage collector. It maintains a linked list of all heap allocations, with a mark bit on each. When memory pressure crosses a threshold (1 MB by default), the GC walks all reachable values from the environment and a shadow root stack, marks what's alive, and sweeps everything else.

The RegionManager manages immutable data using arena-based regions. Each freeze creates a new region backed by a page-based arena — a linked list of 4 KB pages with bump allocation. When a value is frozen, it is deep-cloned entirely into the region's arena, giving crystal data cache locality and enabling O(1) bulk deallocation when the region becomes unreachable. Regions are collected during GC cycles based on reachability analysis.

The key insight here is that immutable and mutable data have different lifecycle characteristics and benefit from different management strategies. Mutable data changes frequently and has unpredictable lifetimes — mark-and-sweep handles this well. Immutable data, once created, never changes and tends to be long-lived — arena-based region allocation is more efficient for this pattern, as it enables bulk deallocation and better cache locality.

This is conceptually similar to generational garbage collection (where young objects are collected differently from old objects), but the split is based on mutability rather than age. Lattice's phase tags provide the runtime with information that generational GCs have to infer statistically.

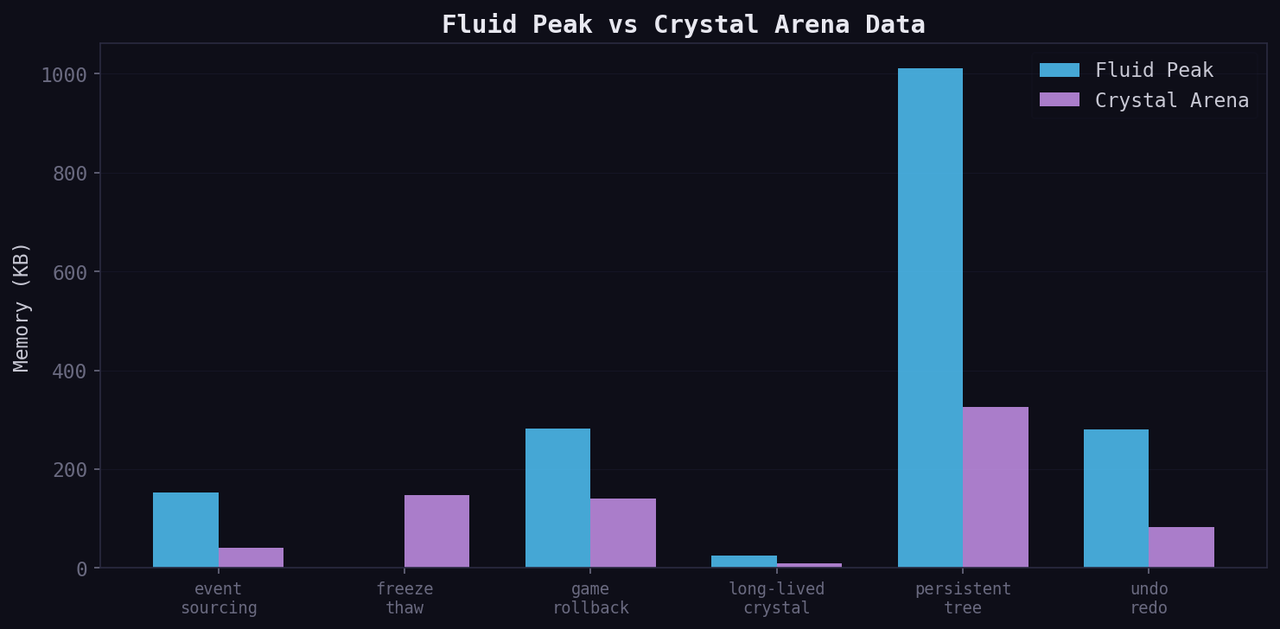

The following chart shows how this plays out in practice across several benchmark programs. Fluid peak memory represents the high-water mark of the GC-managed heap, while crystal arena data shows how much data has been frozen into arena-backed regions:

Freeze and Thaw at the Memory Level

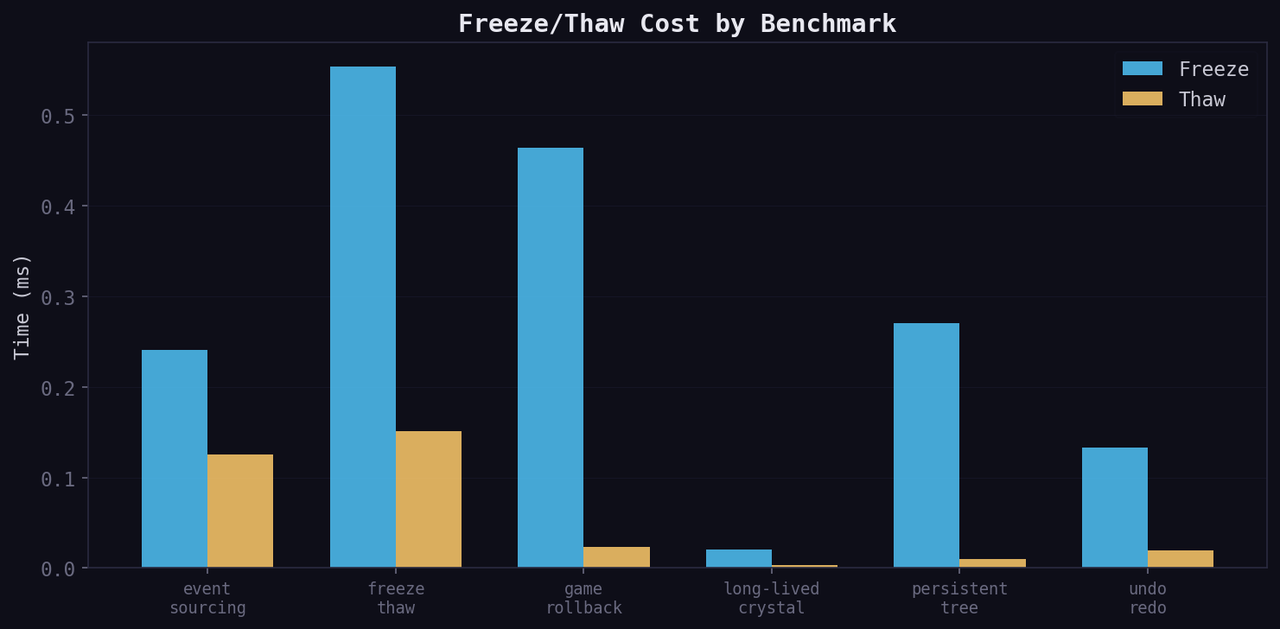

When you call freeze() on a value, the runtime creates a new crystal region with a fresh arena, deep-clones the entire value tree into it, sets the phase field to VTAG_CRYSTAL on every node, and frees the original fluid heap pointers. The data physically migrates from the fluid heap into arena pages — freeze is a move operation, not just a metadata flip. This gives frozen data cache locality within contiguous arena pages and completely separates it from the garbage-collected fluid heap.

But in strict mode, freeze() is also a consuming operation. It removes the original binding from the environment and returns the frozen value. This is effectively a move — after freeze(x), there is no x anymore. You can bind the result to a new name (fix y = freeze(x)), but the mutable original is gone. This prevents a common bug pattern where you freeze a value but accidentally keep mutating the original through a still-live reference.

thaw() is more expensive: it performs a complete deep clone of the crystal value and then recursively sets all phase tags to VTAG_FLUID. The original crystal value is untouched — you get a completely independent mutable copy. This is consistent with the principle that crystal values are permanent. Thawing doesn't melt the original; it creates a new fluid copy.

In practice, both operations are fast. Across the benchmark suite, freeze and thaw costs stay well under a millisecond even for complex data structures:

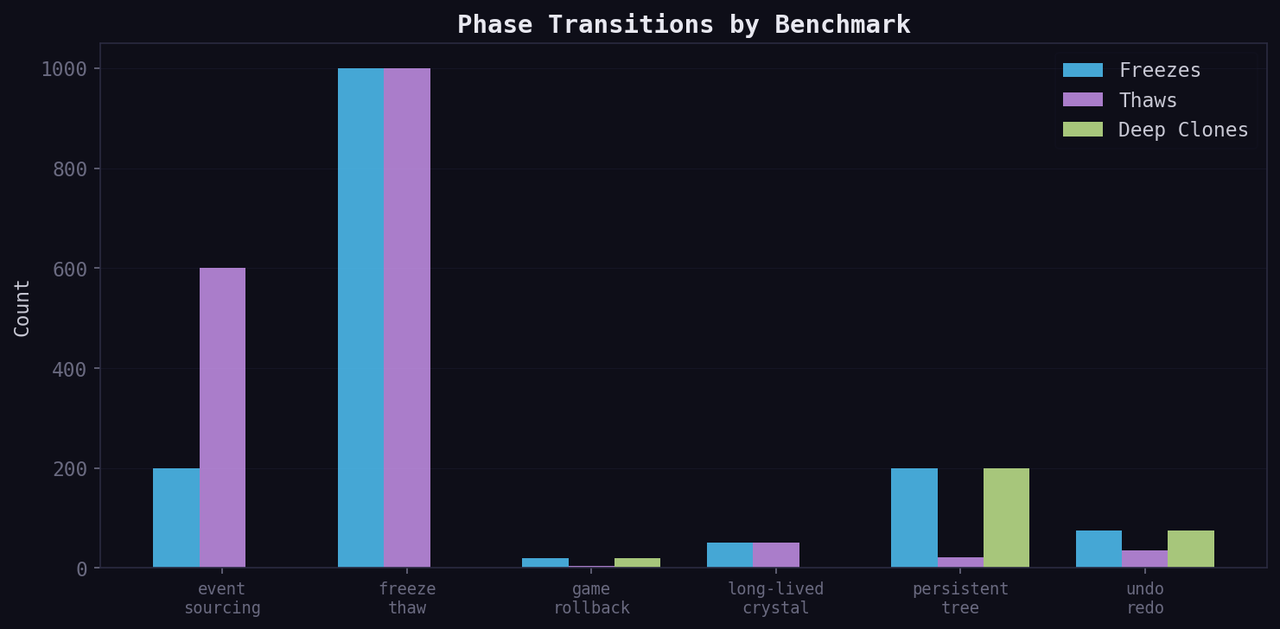

The number and type of phase transitions varies by workload. Some benchmarks are freeze-heavy (building immutable snapshots), others are thaw-heavy (repeatedly modifying frozen state), and some use deep clones for full value duplication:

How This Compares to Existing Systems

vs. Rust's Ownership and Borrowing

Rust solves the mutability problem at compile time through static analysis. The borrow checker ensures that mutable references are unique and that immutable references don't coexist with mutable ones. This gives Rust zero-runtime-cost safety guarantees that Lattice can't match.

But Rust's approach operates at the reference level — it tracks who has access to data, not the data's intrinsic state. You can have an &mut to data that is conceptually "done being built," or an & to data that you wish you could modify. The permission model and the data lifecycle are orthogonal.

Lattice's phase system operates on the data itself. A frozen value is immutable — not because the type system prevents you from obtaining a mutable reference, but because the value has transitioned to a state where mutation doesn't apply. This is a simpler mental model at the cost of runtime enforcement rather than compile-time proof.

The consuming freeze() in strict mode is reminiscent of Rust's move semantics, where using a value after moving it is a compile error. Lattice achieves a similar effect at runtime — freeze consumes the binding, preventing further mutable access. It's not as strong a guarantee (runtime vs. compile time), but it's the same intuition: once you've declared something immutable, the mutable version shouldn't exist anymore.

vs. Garbage Collection

Traditional garbage collectors (Java, Go, Python) are phase-agnostic. They track reachability, not mutability. A final field in Java prevents reassignment but doesn't inform the GC. An immutable object in Python is collected the same way as a mutable one.

Lattice's dual-heap architecture uses phase information to make better allocation decisions. Crystal values go into arena-managed memory with reachability-based collection. Fluid values go into a mark-and-sweep heap. The GC can reason about immutable data more efficiently because it knows the data won't change — it doesn't need to re-scan crystal regions for updated references.

This is a form of phase-informed memory management that, to my knowledge, doesn't have a direct precedent in mainstream languages. The closest analogy might be Clojure's persistent data structures, which are structurally shared and immutable, but Clojure doesn't use this information to drive its garbage collection strategy differently.

vs. Functional Immutability

Haskell and other pure functional languages are immutable by default, with mutation confined to monads (IORef, STRef) or similar controlled mechanisms. This is elegant but can be awkward for imperative algorithms where you need to build something up step by step.

Lattice's forge blocks address this directly. Instead of threading a builder through a chain of pure function calls, you write imperative mutation inside a forge and get an immutable result. This acknowledges that construction and consumption are different activities that benefit from different mutability guarantees.

The philosophical difference is that functional languages treat immutability as the default and mutation as the exception. Lattice treats mutability as a phase that values pass through — both flux and fix are natural, expected states, and the language provides explicit tools for transitioning between them.

vs. C/C++ Manual Memory Management

C gives you malloc and free and wishes you the best. C++ adds RAII, smart pointers, and const correctness, but const in both languages is fundamentally a compiler hint — it can be cast away, and the runtime has no awareness of it. A const pointer in C doesn't prevent someone else from modifying the data through a non-const pointer to the same memory. The const is a property of the reference, not the data.

Lattice's phase tags live on the data itself. When a value is crystal, it's crystal regardless of how you access it. There's no way to "cast away" a freeze — the only path back to mutability is thaw(), which creates a new independent copy. This is a stronger guarantee than const provides, because it operates on values rather than references.

C++ move semantics share DNA with Lattice's consuming freeze() in strict mode. A std::move in C++ transfers ownership of resources, leaving the source in a valid-but-unspecified state. Lattice's strict freeze does something similar — it removes the binding entirely, ensuring the mutable version ceases to exist. But where C++ moves are primarily about avoiding copies for performance, Lattice's consuming freeze is about semantic correctness — ensuring that the transition from mutable to immutable is clean and total. Scott Meyers' Effective Modern C++ remains the best guide to understanding these move semantics and other modern C++ patterns that Lattice's design draws from.

The Static Phase Checker

It's worth noting that Lattice doesn't rely solely on runtime enforcement. Before any code executes, a static phase checker walks the AST and catches phase violations at analysis time. This checker maintains its own scope stack mapping variable names to their declared phases and rejects programs that attempt to reassign crystal bindings, freeze already-frozen values, thaw already-fluid values, or use let in strict mode where an explicit phase declaration is required.

The static checker also enforces spawn boundaries — if Lattice's concurrency model (spawn) is used, fluid bindings from the enclosing scope cannot be captured across the spawn point. Only crystal values can be shared into spawned computations. This is checked before evaluation begins, catching potential data races at parse time rather than at runtime.

This two-layer approach — static checking before evaluation, runtime enforcement during — provides confidence without requiring a full type system or borrow checker. It catches the obvious mistakes early and enforces the subtle invariants at runtime. For the theoretical foundations behind this kind of phase-based type analysis, Benjamin Pierce's Types and Programming Languages is the standard reference.

The Language Beyond Phases

While the phase system is Lattice's defining feature, the language has other characteristics worth noting.

Structs in Lattice can hold closures as fields, enabling object-like patterns without a class system. A struct with function fields and a self parameter in each closure behaves much like an object with methods — but the data flow is explicit, and there's no hidden this pointer or vtable dispatch. When a closure captures self, it receives a deep clone, ensuring that method calls don't produce spooky action at a distance.

Control flow is expression-based — if/else blocks, match expressions, and bare blocks all return values. This reduces the need for temporary variables and makes code more compositional. Error handling uses try/catch blocks with explicit error values rather than exception hierarchies.

The self-hosted REPL is particularly notable. Written entirely in Lattice, it demonstrates that the language is expressive enough to implement its own interactive environment — parsing multi-line input, evaluating expressions, and managing session state. Running ./clat without arguments drops into this REPL, while ./clat file.lat executes a program directly.

Lattice is implemented in C with no external dependencies. The entire codebase — roughly 6,000 lines across the lexer, parser, phase checker, evaluator, and data structures — compiles with a single make invocation. This is a deliberate choice. The language is meant to be small, understandable, and self-contained. You can read the entire implementation in an afternoon. If you're interested in this kind of work, Robert Nystrom's Crafting Interpreters is the best practical guide to building language implementations from scratch — it covers both tree-walking interpreters and bytecode VMs, and Lattice's architecture shares several design decisions with Nystrom's Lox language. For the C implementation side, Kernighan and Ritchie's The C Programming Language remains the definitive reference for writing the kind of clean, minimal C that Lattice targets.

Runtime Characteristics

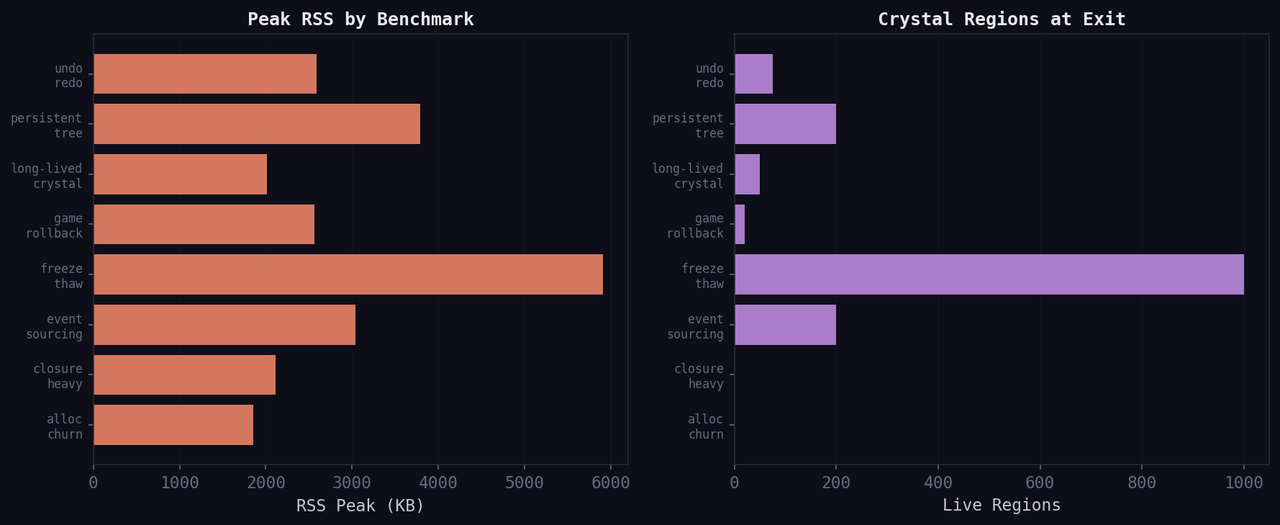

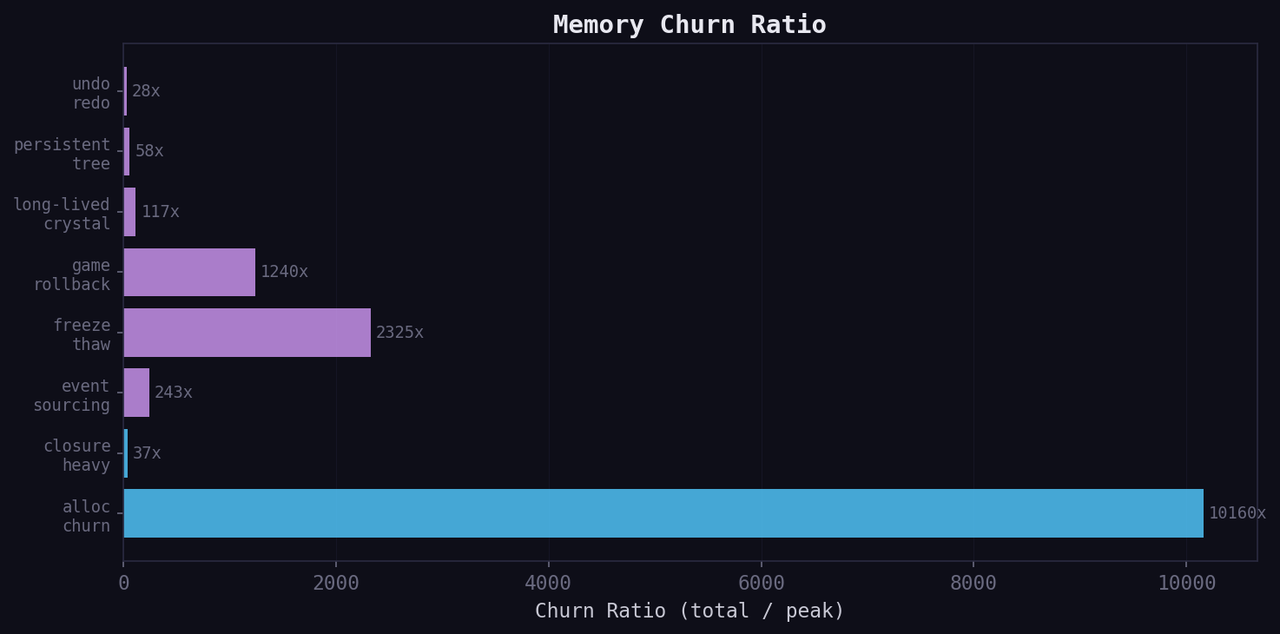

To understand how the dual-heap architecture behaves in practice, Lattice includes a benchmark suite that exercises different memory patterns — allocation churn, closure-heavy computation, event sourcing, freeze/thaw cycles, game state rollback, long-lived crystal data, persistent tree construction, and undo/redo stacks.

The overview below shows peak RSS (resident set size) alongside the number of live crystal regions at program exit. Benchmarks that use the phase system heavily (like freeze/thaw cycles and persistent trees) maintain more live regions, while purely fluid workloads like allocation churn and closure-heavy computation have none:

The memory churn ratio — total bytes allocated divided by peak live bytes — reveals how aggressively each benchmark recycles memory. A high ratio means the program allocates and discards data rapidly, relying on the GC to keep the working set small. Benchmarks using crystal regions (shown in purple) tend to have lower churn because frozen data is long-lived by design:

Research Papers

For readers interested in the formal foundations and empirical analysis, two companion papers are available:

-

The Lattice Phase System: First-Class Immutability with Dual-Heap Memory Management — The full research paper covering the language design, formal operational semantics, six proved safety properties (phase monotonicity, value isolation, consuming freeze, forge soundness, heap separation, and thaw independence), implementation details of the dual-heap architecture, and empirical evaluation across eight benchmarks.

-

Formal Semantics of the Lattice Phase System — A standalone formal treatment containing the complete semantic domains, static phase-checking rules, big-step operational semantics, memory model, and full proofs of all six safety theorems.

Looking Forward

Lattice is at version 0.1.3, which means it's early. The dual-heap architecture is fully wired into the evaluator — freeze operations physically migrate data into arena-backed crystal regions, providing cache locality and O(1) bulk deallocation for immutable data. The mark-and-sweep GC handles fluid values, while crystal regions are collected through reachability analysis during GC cycles.

The deep-clone-on-read strategy is correct but expensive. Future versions may introduce structural sharing for crystal values (since they can't be modified, sharing is safe) or copy-on-write semantics for fluid values that haven't actually been mutated. The phase tags provide the runtime with exactly the information needed to make these optimizations — which values can be shared safely, and which might change.

There's also the question of concurrency. The phase system provides a natural foundation for safe concurrent programming: crystal values can be freely shared across threads (they're immutable), while fluid values are confined to their owning scope. The spawn keyword exists in the parser and phase checker, with static analysis already preventing fluid bindings from crossing spawn boundaries — though concurrent execution isn't yet implemented.

The source code is available on GitHub under the BSD 3-Clause license, and the project site is at lattice-lang.org. If you're interested in language design, memory management, or just want to play with a language that treats mutability as a physical process rather than a type annotation, it's worth a look.

git clone https://github.com/ajokela/lattice.git cd lattice && make ./clat