Before there were photorealistic graphics and ray tracing, before polygons and sprites, there was something far more powerful: your imagination. In the late 1970s, a group of MIT hackers created a game that would define an entire genre and influence gaming for decades to come. This is the story of Infocom and their masterpiece, Zork.

The Birth of Interactive Fiction

The story of Zork begins not with Infocom, but with a cave. In 1975, Will Crowther, a programmer at Bolt, Beranek and Newman (the company that built the ARPANET), created a text-based game called Adventure (also known as Colossal Cave Adventure). Crowther was an avid caver, and he combined his knowledge of Kentucky's Mammoth Cave system with fantasy elements inspired by Dungeons & Dragons. The game spread across ARPANET like wildfire, captivating programmers at universities and research institutions worldwide.

Among those captivated were several students and staff at MIT's Laboratory for Computer Science, working on the Dynamic Modeling Group's PDP-10 mainframe. In 1977, Marc Blank, Dave Lebling, Tim Anderson, and Bruce Daniels decided they could do better. They set out to create a more sophisticated adventure game with a richer world, better puzzles, and a far more capable text parser that could understand complex English sentences.

They called their creation Zork - a nonsense word used as a placeholder during MIT projects. The name stuck.

In this 1985 interview from Computer Chronicles, Dave Lebling discusses Infocom's approach to interactive fiction and what made their games unique:

Zork: The Great Underground Empire

The original mainframe Zork was massive by the standards of the day. Written in MDL (a LISP-like language), it occupied over a megabyte of memory - an absurd amount when most personal computers had 16KB or 32KB at most. The game featured hundreds of locations, dozens of objects, and a parser that could understand sentences like "put the jeweled egg in the trophy case" or "attack the troll with the elvish sword."

The premise was simple yet irresistible: you are an adventurer exploring the ruins of the Great Underground Empire, a vast subterranean realm filled with treasures, dangers, and puzzles. The white house. The mailbox. The brass lantern. The thief. The grues lurking in the darkness. These elements became iconic, instantly recognizable to anyone who played.

What set Zork apart from Adventure was its sophistication. The parser understood prepositions, adjectives, and complex commands. The game responded intelligently to absurd inputs, often with dry wit. The puzzles were clever and interconnected. And the writing - sparse, evocative, occasionally hilarious - created a world more vivid than any graphics could render.

"It is pitch black. You are likely to be eaten by a grue."

That single sentence has become one of gaming's most famous lines.

From Mainframe to Microcomputer: The Founding of Infocom

By 1979, the Zork creators faced a problem and an opportunity. The game was hugely popular among the relatively small community of people with access to mainframes, but personal computers were beginning to proliferate. The Apple II, TRS-80, and Commodore PET were bringing computing into homes. Could Zork be brought to these machines?

The technical challenges were formidable. Zork was written in MDL for a PDP-10 with vast resources. Personal computers had neither the memory nor the processing power to run it directly. The solution came from Joel Berez, a recent MIT graduate, and Marc Blank: create a virtual machine.

They called it the Z-machine. Instead of porting Zork directly to each platform, they would write a compact virtual machine interpreter for each computer and compile Zork into a bytecode format (called a "story file") that any Z-machine could run. This was brilliant engineering - write once, run anywhere, decades before Java made the concept mainstream.

The Z-machine's influence extended beyond Infocom. When Lucasfilm Games faced the same cross-platform challenge in 1987, Ron Gilbert and Aric Wilmunder created SCUMM (Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion) - a scripting engine and virtual machine that powered Maniac Mansion, Monkey Island, and dozens of other LucasArts adventures. While there's no documented direct lineage, the architectural similarity is unmistakable: both systems abstracted game logic from hardware, both used bytecode interpreters, and both solved the 1980s problem of incompatible platforms with elegant virtualization. Today, both live on through modern reimplementations - Frotz and other interpreters run original Infocom story files, while ScummVM preserves the LucasArts catalog.

In June 1979, the founders incorporated Infocom in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The company's mission was straightforward: bring Zork to personal computers and see if people would pay for it.

They split the massive mainframe Zork into three parts, each substantial enough to be a full game. Zork I: The Great Underground Empire shipped in 1980 for the PDP-11 and appeared on the TRS-80 in 1981. It was an immediate hit.

The Golden Age of Infocom

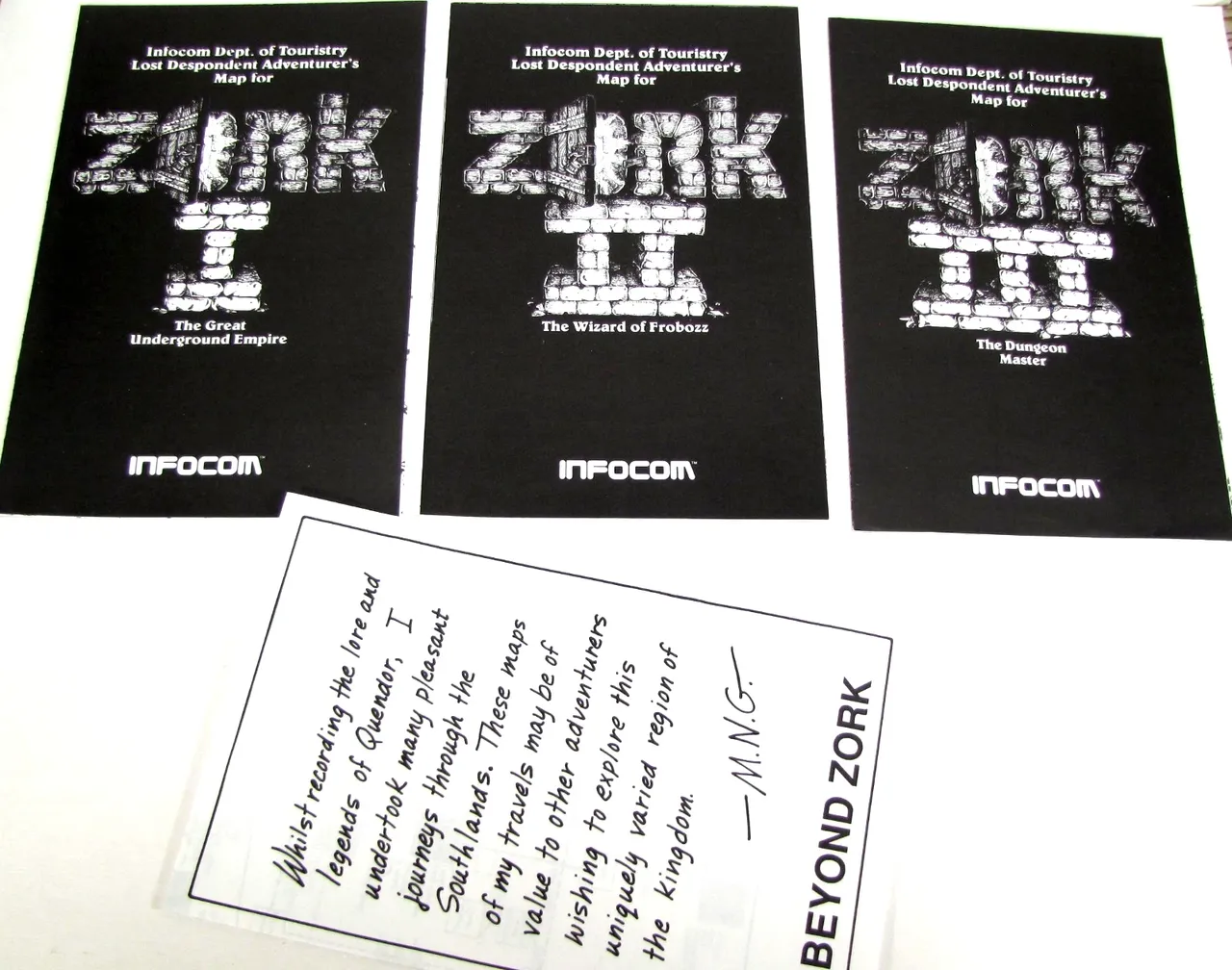

The early 1980s were Infocom's golden years. The Z-machine proved its worth, allowing the company to release games simultaneously across multiple platforms with minimal porting effort. After completing the Zork trilogy (Zork I, Zork II: The Wizard of Frobozz, and Zork III: The Dungeon Master), Infocom expanded into other genres.

Deadline (1982) pioneered the interactive mystery, dropping players into a murder investigation with real-time elements and multiple endings. Suspended (1983) put players in control of a complex through six robots, each with different capabilities. Planetfall (1983) introduced humor and emotional depth through Floyd, a childlike robot companion whose fate remains one of gaming's most affecting moments.

The games were uniformly excellent, but Infocom distinguished itself in another way: packaging. Each game came in an elaborate box filled with "feelies" - physical props that enhanced the experience and served as copy protection. A Deadline box contained a police interview transcript, pills from the crime scene, and a coroner's report. The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy included pocket fluff, a button proclaiming "Don't Panic," and a pair of Peril Sensitive Sunglasses (opaque black cardboard glasses).

This was premium entertainment at premium prices, and customers loved it.

The Hitchhiker's Guide and Literary Ambitions

In 1984, Infocom achieved something remarkable: a collaboration with Douglas Adams, author of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. Adams worked directly with designer Steve Meretzky to create an interactive version of his beloved absurdist science fiction comedy.

The game was deliberately, gloriously unfair. It featured puzzles that couldn't be solved without items collected hours earlier, locked players in unwinnable states without warning, and regularly killed the player for seemingly innocuous actions. It was also brilliant, capturing Adams's wit and subversive humor perfectly. The game sold 350,000 copies, Infocom's biggest hit.

But Hitchhiker's also revealed Infocom's split personality. The company saw itself not just as a game developer but as a publisher of "interactive fiction" - a literary form deserving respect alongside traditional novels. This artistic ambition was genuine and produced remarkable work like A Mind Forever Voyaging (1985), which explored a dystopian future through time-jumping vignettes, and Trinity (1986), a meditation on nuclear weapons that remains one of the most ambitious games ever made.

The problem was that artistic ambition doesn't always translate to commercial success.

The Business That Broke Them

Infocom's downfall didn't come from their games - it came from a database product called Cornerstone.

By 1984, Infocom was generating significant revenue from games, but investors and management believed the future lay in business software. They developed Cornerstone, a relational database for business users that was technically impressive and received strong reviews. It was also expensive to develop and entered a market dominated by Ashton-Tate's dBase.

The Cornerstone disaster was comprehensive. Development costs ballooned. Sales were disappointing. By 1985, Infocom was losing money rapidly despite strong game sales. The company that had bootstrapped itself on games now needed outside investment to survive.

Enter Activision.

Acquisition by Activision

In 1986, Activision acquired Infocom for approximately $7.5 million. On paper, the deal made sense: Activision got a prestigious studio with a loyal customer base, and Infocom got capital to continue operations.

In practice, the acquisition was contentious from the start. Activision was a very different company - focused on graphics-heavy console and computer games, not text adventures. Cultural clashes were immediate and severe. The Cornerstone division was shut down, but the damage was done: Infocom had lost money, lost momentum, and lost the confidence of its new parent.

Activision pressed Infocom to add graphics to their games, believing text-only adventures were becoming obsolete. Games like Beyond Zork (1987) and Zork Zero (1988) featured graphical elements, attempting to bridge old and new paradigms. The results were mixed - loyal fans felt betrayed while new audiences weren't convinced.

The market was shifting away from text adventures. The NES was ascendant. Computer games were becoming increasingly graphical. Infocom's sales declined. Staff left or were laid off. Marc Blank had departed by 1986. Dave Lebling stayed until 1989.

In 1989, Activision finally closed the Infocom offices in Cambridge. The last game released under the original Infocom banner was Shogun (1989). The company that had defined a genre was effectively dead, absorbed into its acquirer after just three years.

The Intellectual Property Journey

But Zork didn't die with Infocom. The intellectual property continued its journey through corporate America's M&A machinery.

Activision attempted to revive the brand periodically. Return to Zork (1993) was a graphical adventure game that traded text for full-motion video. Zork Nemesis (1996) and Zork: Grand Inquisitor (1997) followed in the Myst-inspired point-and-click adventure style. These games sold reasonably well but felt distant from Infocom's text-based origins.

Activision merged with Blizzard Entertainment in 2008, forming Activision Blizzard. The Infocom and Zork properties came along for the ride, sitting in a vast intellectual property portfolio that included Call of Duty, World of Warcraft, and Candy Crush (after the King acquisition in 2016).

Then came the biggest acquisition in gaming history. In January 2022, Microsoft announced it would acquire Activision Blizzard for $68.7 billion. After regulatory battles across multiple continents, the deal closed in October 2023. Microsoft now owned not just Call of Duty and World of Warcraft, but also Zork.

The game that began as a project by MIT hackers in 1977 now belongs to one of the world's largest technology companies. Somewhere in Microsoft's intellectual property databases, alongside Minecraft, Halo, and Doom, sits the rights to a brass lantern, a rubber raft, and a maze of twisty little passages, all alike.

The Legacy of Infocom

Infocom's direct output was relatively small: about 35 games over ten years. But their influence far exceeds their catalog.

The Z-machine was ahead of its time. Its philosophy of platform-independent bytecode influenced later virtual machines and interpreters. When fans reverse-engineered the format in the 1990s, they created the Inform programming language, which remains the dominant tool for creating interactive fiction today. New Z-machine interpreters exist for every platform imaginable, from modern web browsers to vintage calculators.

The writing standards Infocom established remain the benchmark. Their games proved that text could create experiences as immersive as any visual medium - that a skilled writer could make a player feel genuine fear, joy, grief, or triumph through words alone.

The "Great Underground Empire" and its associated lore have become part of gaming's shared cultural heritage. Grues are referenced in everything from World of Warcraft to Minecraft. The concept of "interactive fiction" that Infocom championed has evolved into a thriving indie scene, producing works that push the boundaries of what games can be.

Most importantly, Infocom proved that games could aspire to be art. Not every game needs to chase that goal, but the possibility exists because companies like Infocom demonstrated it was achievable.

Playing Zork Today

The original Zork games remain playable and are freely available online. Various interpreters run the original story files on any modern system. Fire up a Z-machine interpreter, load ZORK1.DAT, and you'll see:

ZORK I: The Great Underground Empire Copyright (c) 1981, 1982, 1983 Infocom, Inc. All rights reserved. ZORK is a registered trademark of Infocom, Inc. Revision 88 / Serial number 840726 West of House You are standing in an open field west of a white house, with a boarded front door. There is a small mailbox here. >

Or better yet - play it right here. The embedded player below uses Encrusted, a Z-machine interpreter written in Rust and compiled to WebAssembly. Zork I loads automatically - just start typing commands.

Forty-five years later, the magic remains intact. No graphics. No sound beyond your imagination. Just words on a screen and a world waiting to be explored.

Open the mailbox.