Introduction

There's a certain satisfaction in making old hardware do new tricks. When NVIDIA released the Tesla P40 in 2016, deep learning was still finding its footing. ImageNet classification was the benchmark everyone cared about, GANs were generating blurry faces, and the idea of a 57-billion-parameter image editing model would have seemed like science fiction.

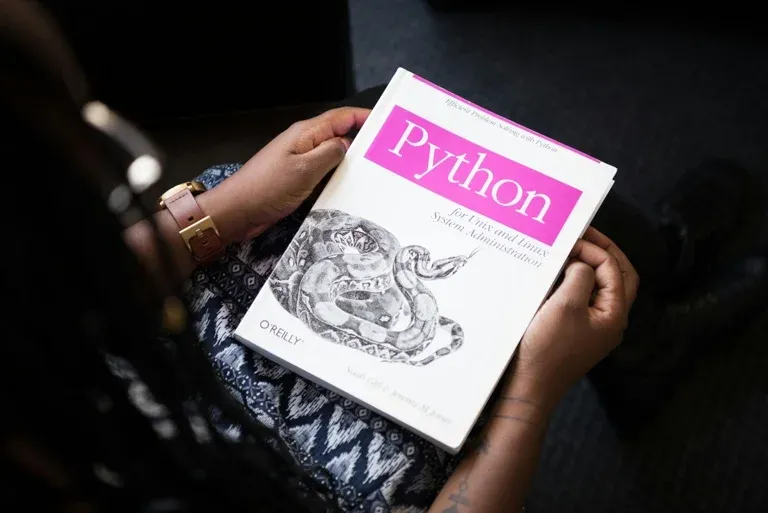

Around the middle of 2017, when the P40 would have been seeing peak adoption in datacenters, I found myself in an advanced pattern recognition course, my final credits needed for a masters in computer science — the name hadn't been updated to reflect more contemporary terminology like "machine learning," let alone "deep learning." The textbook was Bishop's Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning, a book that managed to make Bayesian inference feel both rigorous and approachable. We spent the last two weeks of the course looking at deep learning using TensorFlow, but we didn't even have GPU infrastructure available. Everything ran on CPU. It would have been great to have experienced the P40 in its prime, when 24 GB of VRAM and 3,840 CUDA cores made it one of the most capable inference GPUs money could buy. Instead, I'm getting acquainted with it a decade later, asking it to do things its designers never imagined.

Fast forward to 2026, and here I am, running a 57-billion-parameter model on four of these decade-old GPUs — and comparing the results against AMD's latest Strix Halo APU, a chip that didn't exist until 2025.

The model in question is FireRed-Image-Edit-1.0 from FireRedTeam, a 57.7GB diffusion model built on the QwenImageEditPlusPipeline architecture. It takes an input image and a text prompt, then produces an edited version. The kind of thing that would have required a massive cloud GPU a couple of years ago.

This post documents the full journey: the precision pitfalls of running modern diffusion models on Pascal-era GPUs, the quantization trade-offs that make or break image quality, and the head-to-head performance comparison that produced some genuinely surprising results. All of the inference scripts and output images are available on GitHub.

The Hardware

NVIDIA Tesla P40 (2016)

The P40 was NVIDIA's inference-focused datacenter GPU from the Pascal generation. The key specs for our purposes:

- Architecture: Pascal (sm_6.1)

- CUDA Cores: 3,840

- Memory: 24 GB GDDR5X

- Memory Bandwidth: 346 GB/s

- FP32 Performance: 12 TFLOPS

- FP16 Performance: Limited — no native FP16 tensor cores

- BF16 Support: None

- Price today: ~$100-200 per card on the secondary market

I have four of these cards in a server, giving me 96 GB of total VRAM — but spread across four separate memory spaces, which introduces its own challenges.

AMD Ryzen AI MAX+ 395 / Strix Halo (2025)

AMD's Strix Halo is a different beast entirely. It's an APU — CPU and GPU on the same die, sharing the same memory pool:

- GPU Architecture: RDNA 3.5 (gfx1151)

- Compute Units: 40 CUs

- Memory: 128 GB unified LPDDR5X (32 GB for CPU, 96 GB for VRAM)

- Memory Bandwidth: ~256 GB/s (shared)

- BF16 Support: Yes

- FP16 Support: Yes (Fast F16 Operation)

- ROCm: 7.9.0

- Price: ~$2,000+ for the complete system

The unified memory architecture means all 96 GB is accessible to the GPU without any PCIe transfer overhead, and the entire model can live in a single memory space.

The Model: FireRed-Image-Edit-1.0

FireRed-Image-Edit is a diffusion-based image editing model with three major components:

| Component | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Transformer | 40.9 GB | QwenImageTransformer2DModel, 60 layers |

| Text Encoder | 16.6 GB | Qwen2.5-VL 7B vision-language model |

| VAE | ~0.3 GB | AutoencoderKL for encoding/decoding images |

Total: 57.7 GB of model weights. The scheduler is FlowMatchEulerDiscreteScheduler, and the pipeline uses true classifier-free guidance (CFG), which roughly doubles the memory needed during inference since it runs both conditional and unconditional passes.

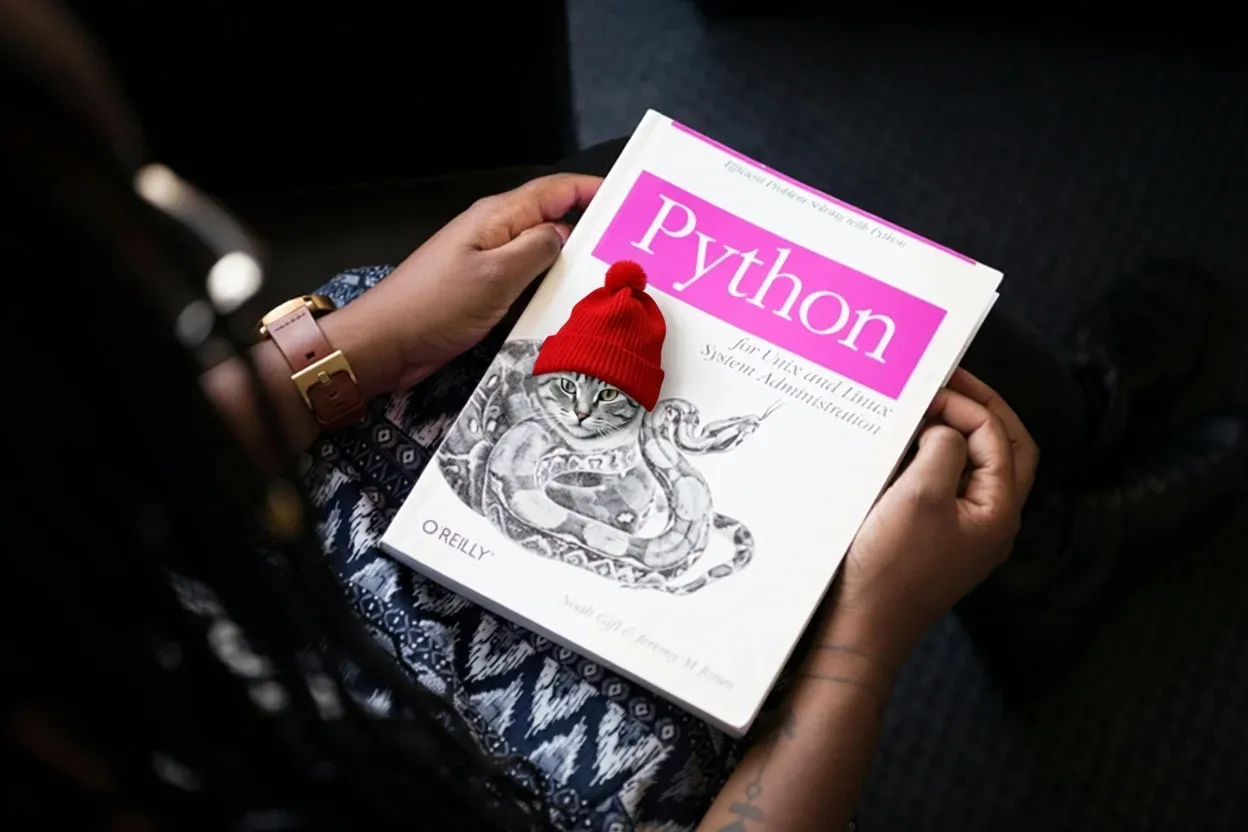

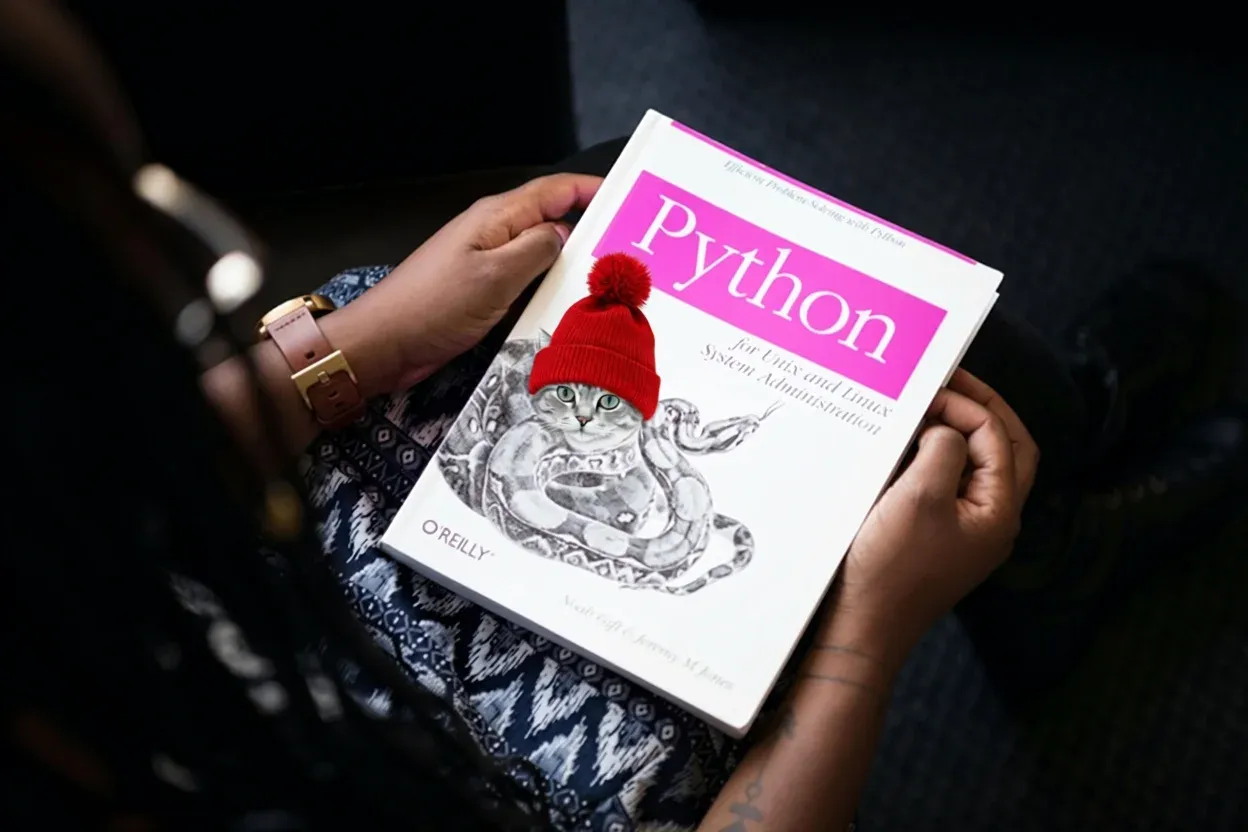

The test task: take this input image and apply the prompt "Add a red hat on the cat" — the model draws a cat wearing a red hat onto the book cover, rendered in the style of the O'Reilly animal illustrations.

The P40 Challenge: When FP16 Breaks Everything

The Precision Problem

The first — and biggest — challenge with the P40s is numerical precision. Modern diffusion models are designed for BF16 (bfloat16), which has the same exponent range as FP32 (8 exponent bits, range ±3.4×10³⁸) but with reduced mantissa precision. The P40, being a Pascal-era GPU, supports neither BF16 nor proper FP16 tensor operations.

FP16 has only 5 exponent bits, giving it a range of ±65,504. This might seem sufficient, but the diffusion scheduler's internal sigma values and the VAE's convolution operations routinely produce intermediate values that overflow this range. The FlowMatchEulerDiscreteScheduler, in particular, works with sigma schedules that can produce large intermediate values during the noise prediction and scaling steps. When these overflow FP16's limited range, they become NaN or Inf, and these corrupt values propagate through every subsequent operation — matrix multiplications, attention computations, residual connections — until the entire tensor is garbage.

The result: NaN propagation that silently corrupts the entire pipeline, producing an all-black output image.

This was the most time-consuming discovery in the entire project. The model would load, the progress bar would advance through all 40 denoising steps without any indication of trouble, and then the output would be perfectly black — mean=0.0, min=0, max=0. No error messages. No warnings. No NaN detection exceptions. Just silent numerical corruption that only becomes visible when you look at the final image.

The debugging process was particularly frustrating because the corruption happens gradually. Partial NaN contamination in early steps doesn't crash anything — the attention mechanisms and residual connections continue to produce tensor outputs of the expected shapes. The model appears to be working normally right up until the final image is decoded from all-zero latents.

The FP32 Solution (and a Speed Surprise)

The fix was to run the entire pipeline in FP32 — scheduler, VAE, and all non-quantized transformer layers. The quantized weights themselves stay compressed (INT8 or NF4), but every arithmetic operation uses full 32-bit precision.

It wasn't enough to just set the quantization compute dtype to FP32 — that only fixes the dequantized matmul operations inside the quantized layers. The scheduler's sigma arithmetic, the VAE's convolution operations, and the non-quantized components (layer norms, biases, attention scaling) all needed FP32 as well. Similarly, loading the pipeline with torch_dtype=torch.float32 but leaving the transformer's non-quantized layers in FP16 caused a dtype mismatch in the attention mechanism — PyTorch's scaled dot-product attention requires query, key, and value tensors to share the same dtype. Every component in the computational chain needed to be FP32.

The one exception is the text encoder, which runs once before the denoising loop begins. It stays in FP16 on its own GPU, and its output embeddings are upcast to FP32 when transferred to the main device. This is safe because the text encoder doesn't participate in the iterative process where precision errors compound.

Here's where things got interesting: FP32 was actually faster than FP16 on the P40. The first attempts with FP16 ran at approximately 9 minutes per denoising step. After switching to FP32, the same operations completed in about 2.4 minutes per step with NF4, and 1.5 minutes per step with INT8. The P40's FP32 throughput is its native strength — it was designed for FP32 datacenter inference, after all. FP16 on Pascal is handled through slower pathways that add overhead rather than saving it.

Multi-GPU Device Orchestration

With 57.7 GB of model weights and only 24 GB per GPU, some form of model sharding or quantization is mandatory. After extensive testing, the optimal configuration for the P40s turned out to be:

- GPU 0: INT8-quantized transformer (~22 GB)

- GPU 1: Text encoder in FP16 (~16.6 GB)

- GPU 2: VAE in FP32 (~6.6 GB including decode workspace)

- GPU 3: Unused

This layout requires significant monkey-patching of the diffusers pipeline. The _execution_device property must be overridden to ensure latents are created on the correct GPU. The encode_prompt method needs patching to route inputs to the text encoder's GPU and move the resulting embeddings back. And for the INT8 configuration, the VAE's encode and decode methods need wrappers to handle cross-device tensor transfers.

The text encoder stays in FP16 because it fits on a single GPU and its outputs are immediately upcast to FP32 when moved to the main device. This is safe because the text encoder runs once at the beginning — it doesn't participate in the iterative denoising loop where precision matters most.

Quantization Quality: INT8 vs NF4

With the FP32 pipeline in place, I tested both INT8 (8-bit) and NF4 (4-bit) quantization for the transformer:

NF4 (4-bit quantization): The NF4 approach uses bitsandbytes' normalized float 4-bit quantization with double quantization enabled. The transformer compresses from 40.9 GB to roughly 10 GB, easily fitting on a single P40 alongside the VAE. However, the output quality was significantly degraded — heavy noise and grain throughout the image, even at the full 40 denoising steps. Each denoising step introduces small numerical errors from the 4-bit weight approximations, and these errors compound across 40 iterations.

INT8 (8-bit quantization): INT8 produced dramatically better results. The output was clean and sharp, visually comparable to what you'd expect from full-precision inference on a modern GPU. The 8-bit precision preserves enough information in the weights that the per-step errors don't accumulate into visible artifacts.

The trade-off is memory: the INT8 transformer occupies ~22 GB, nearly filling an entire P40. This is why the VAE had to move to a third GPU — there wasn't enough headroom on GPU 0 for the VAE's convolution workspace during the decode phase. An early attempt that kept the VAE on GPU 0 ran all 40 denoising steps successfully, only to crash with an out-of-memory error at the very last operation.

The Strix Halo Experience: Simplicity Wins

BF16 Full Precision

Running the same model on the Strix Halo was refreshingly simple. With 96 GB of unified VRAM and native BF16 support, the entire pipeline loads in a few lines:

pipe = QwenImageEditPlusPipeline.from_pretrained( model_path, torch_dtype=torch.bfloat16, ) pipe.to("cuda:0")

No quantization. No multi-GPU patching. No device transfer hooks. No FP32 workarounds. The model loads in BF16 and runs natively.

During inference, the pipeline consumed approximately 75 GB of VRAM (the true CFG doubles the workspace requirements), well within the 96 GB budget.

The first run did take about 35 minutes of JIT kernel compilation before producing any inference steps — ROCm compiles HIP kernels for the gfx1151 architecture on first use. During this phase, the GPU sits at 100% utilization with no visible progress, which can be alarming if you're not expecting it. The GPU temperature climbed from 31°C idle to 69°C, and power draw went from 9W to 119W as the compiler worked through the hundreds of unique kernel configurations needed by a 60-layer transformer. These compiled kernels are cached, so subsequent runs skip this overhead entirely.

Quantization on Strix Halo: Does It Help?

Given the surprising performance parity between the two systems at full precision, I tested whether quantization could speed up the Strix Halo by reducing memory traffic. The theory was that if the workload is memory-bandwidth-limited, smaller model weights should mean faster inference.

The results were definitive:

| Configuration | Per-Step Time | 40-Step Estimate | VRAM Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| BF16 (full precision) | 82.6s | 55 min | ~75 GB |

| NF4 (4-bit) | 83.5s | 56 min | ~30 GB |

| INT8 (8-bit) | 94.9s | 63 min | ~44 GB |

NF4 quantization produced virtually identical speed to full BF16. The model shrank from 75 GB to 30 GB of VRAM usage, but inference time didn't improve at all. INT8 was actually slower — the bitsandbytes INT8 matmul path adds dequantization overhead that more than offsets any memory bandwidth savings.

This tells us something important about the Strix Halo's performance profile for this workload: it's compute-bound, not memory-bound. The RDNA 3.5 GPU's 40 compute units are the bottleneck, not the LPDDR5X memory bandwidth. Reducing the model size doesn't help because the GPU is already busy with arithmetic, not waiting on memory.

This contrasts with LLM inference workloads (text generation), where the Strix Halo's large memory pool is a genuine advantage — LLM token generation is almost entirely memory-bound, making quantization directly translate to speed improvements. Each token generation pass reads the entire model's weights but performs relatively little computation per weight. Diffusion models are the opposite: each denoising step runs a full forward pass through 60 transformer layers with dense matrix multiplications, attention computations, and residual connections. The arithmetic intensity is much higher, putting the pressure squarely on the GPU's compute units rather than its memory subsystem.

Head-to-Head: The Numbers

Here's the complete performance comparison across all tested configurations:

| System | Configuration | Per-Step | 40 Steps | Image Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strix Halo | BF16 full precision | 82.6s | 55 min | Clean, sharp |

| Strix Halo | NF4 (4-bit) | 83.5s | 56 min | Clean (10-step test) |

| Strix Halo | INT8 (8-bit) | 94.9s | 63 min | Clean (10-step test) |

| 4× P40 | INT8 + FP32 pipeline | 87.5s | 58 min | Clean, sharp |

| 4× P40 | NF4 + FP32 pipeline | 145.9s | 97 min | Heavy noise/grain |

The headline result: a single AMD Strix Halo APU from 2025 is about 6% faster per step than four NVIDIA P40s from 2016 running INT8-quantized inference. That's not exactly the generational leap you might expect from a decade of GPU evolution.

To be fair, the comparison isn't entirely apples-to-apples. The P40 is running an 8-bit quantized model (less computation per step but with dequantization overhead), while the Strix Halo runs the full BF16 model. The P40's dedicated GDDR5X provides 346 GB/s of bandwidth to a single GPU, while the Strix Halo's LPDDR5X shares its ~256 GB/s between the CPU and GPU. And the P40 setup requires three GPUs working in concert, while the Strix Halo uses a single unified memory space.

Lessons Learned

Old GPUs Are Surprisingly Capable

Four P40s at ~$500 total produce inference quality and speed that's competitive with a $2,000+ modern APU system. The P40's 346 GB/s memory bandwidth per card and strong FP32 throughput remain relevant even for models that were designed for hardware two generations newer. The main challenge is software engineering — working around the precision limitations and multi-GPU complexity takes significant effort.

Precision Matters More Than Speed

The single most impactful discovery in this project was that FP16 silently corrupts diffusion model outputs on Pascal GPUs. There are no error messages, no NaN warnings during inference — just a black image at the end. The fix (using FP32 everywhere) actually improved performance, which was counterintuitive. The lesson: when dealing with older hardware, always validate your numerical precision assumptions before optimizing for speed.

Quantization Is Not Free

On the P40s, INT8 quantization was essential (the model simply wouldn't fit otherwise) and produced excellent results. NF4 was too aggressive — the 4-bit precision degraded output quality visibly.

On the Strix Halo, quantization was unnecessary and even counterproductive. INT8 added overhead without any speed benefit, and NF4 didn't save time despite dramatically reducing memory usage. The takeaway: quantization's value depends entirely on your bottleneck. If you're compute-bound, smaller weights don't help.

Unified Memory Is Underrated

The Strix Halo's greatest advantage wasn't raw performance — it was simplicity. Loading a 57.7 GB model into a single 96 GB memory space eliminates an entire category of engineering problems: no device placement, no cross-GPU tensor transfers, no monkey-patching encode/decode methods, no VAE OOM surprises at the decode step. The inference script for the Strix Halo is about 50 lines. The P40 version is over 150, most of it careful device orchestration code.

For anyone who values development velocity and code maintainability over squeezing the last dollar of cost-efficiency out of used datacenter hardware, unified memory APUs have a compelling argument even when they don't win on raw throughput.

What About Newer NVIDIA GPUs?

It's worth putting these numbers in context. An NVIDIA RTX 4090 with 24 GB of VRAM and native BF16/FP16 tensor core support would likely run this model (with INT8 quantization) at roughly 10-15 seconds per step — 5-8x faster than either system tested here. An A100 with 80 GB could run it unquantized in BF16 at similar or better speeds. The P40 and Strix Halo are both firmly in the "budget/accessible" tier of AI hardware.

The more interesting comparison is cost-per-step. Four P40s from eBay cost about $500 total (plus a server that can host them). The Strix Halo system runs about $2,000+. Both produce essentially the same result at the same speed. The P40 route demands more engineering knowledge; the Strix Halo route demands more money.

Conclusion

Both systems successfully ran a 57.7 GB diffusion model that would have been considered impossibly large for consumer hardware just a few years ago. The P40s did it through clever quantization and multi-GPU orchestration. The Strix Halo did it by brute force — 96 GB of memory and native BF16 support.

The performance story is more nuanced than "newer is always better." For diffusion model inference, the NVIDIA P40 — a card you can buy for $100 on eBay — remains remarkably competitive when properly configured. It requires more engineering effort, and you need to know the precision pitfalls, but the results speak for themselves.

The Strix Halo's strength lies not in raw speed but in its unified memory architecture and modern instruction set support. It eliminates the multi-GPU complexity entirely, runs native BF16 without precision hacks, and provides a development experience that's orders of magnitude simpler. For iterating on models, testing new architectures, or just avoiding the headaches of cross-device tensor management, that simplicity has real value.

If you're considering hardware for running large diffusion models locally, the choice comes down to how you value your time versus your budget. Four P40s and a weekend of debugging will get you to roughly the same place as a Strix Halo system that just works out of the box. Both paths lead to a cat in a red hat.

Recommended Resources

Hardware

- NVIDIA Tesla P40 24GB - The GPU used in this post. Available on eBay for a fraction of the original price. You'll need a server with PCIe x16 slots and adequate cooling.

- GMKtec EVO-X2 (AMD Ryzen AI MAX+ 395) - A compact Strix Halo mini PC with 128GB unified LPDDR5X 8000MHz, WiFi 7, and USB4. A representative platform for running large models on Strix Halo.

Books

- Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning by Christopher M. Bishop - The classic that introduced many to Bayesian methods and kernel machines. Still one of the best foundations for understanding the statistical principles behind modern ML.

- Hands-On Generative AI with Transformers and Diffusion Models by Omar Sanseviero, Pedro Cuenca, Apolinário Passos, and Jonathan Whitaker - A practical guide to building and fine-tuning diffusion models using the Hugging Face ecosystem, including the diffusers library used in this post.

- Understanding Deep Learning by Simon J.D. Prince - A thorough modern treatment of deep learning fundamentals through diffusion models, with excellent visualizations and mathematical rigor.