The Horizon X3 CM: A Cautionary Tale in Robotics Development Platforms

Introduction

The Horizon X3 CM (Compute Module) represents an interesting case study in the single-board computer market: a product marketed as an AI-focused robotics platform that, in practice, falls dramatically short of both its promises and its competition. Released during the 2021-2022 timeframe and based on Horizon Robotics' Sunrise 3 chip (announced September 2020), the X3 CM attempts to position itself as a robotics development platform with integrated AI acceleration through its "Brain Processing Unit" or BPU. However, as we discovered through extensive testing and configuration attempts, the Horizon X3 CM is an underwhelming offering that suffers from outdated hardware, broken software distributions, abandoned documentation, and a configuration process so Byzantine that it borders on hostile to users.

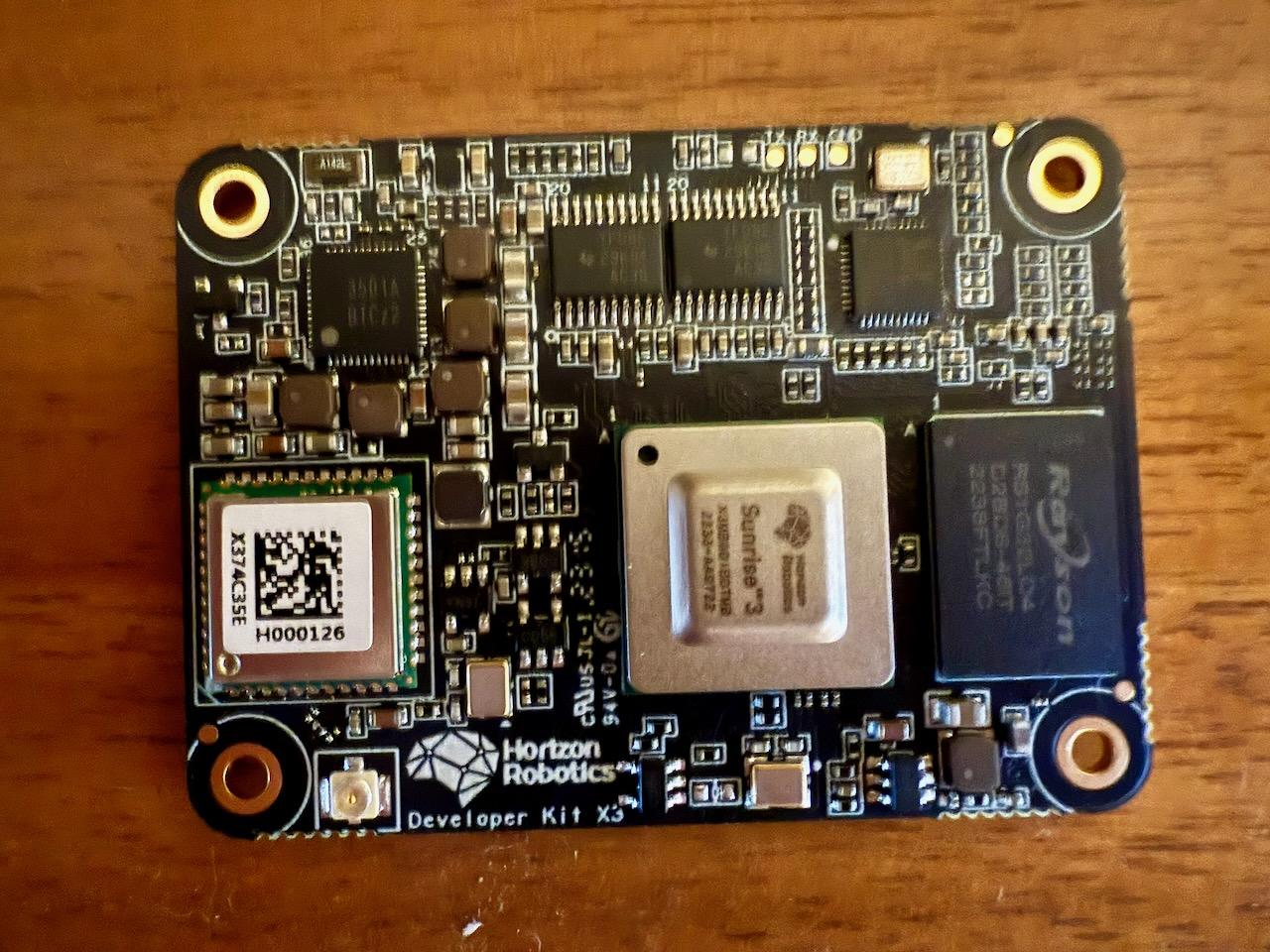

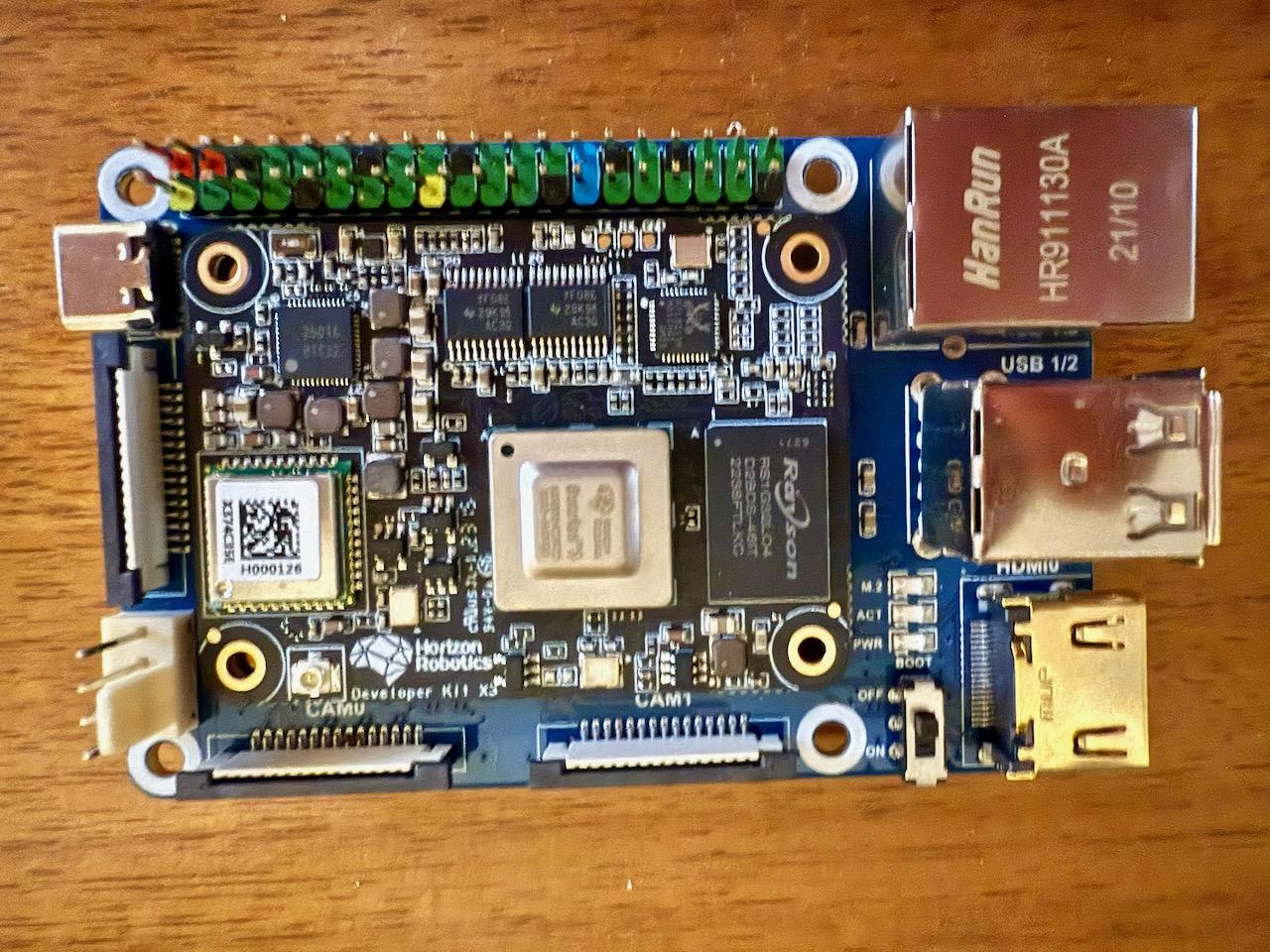

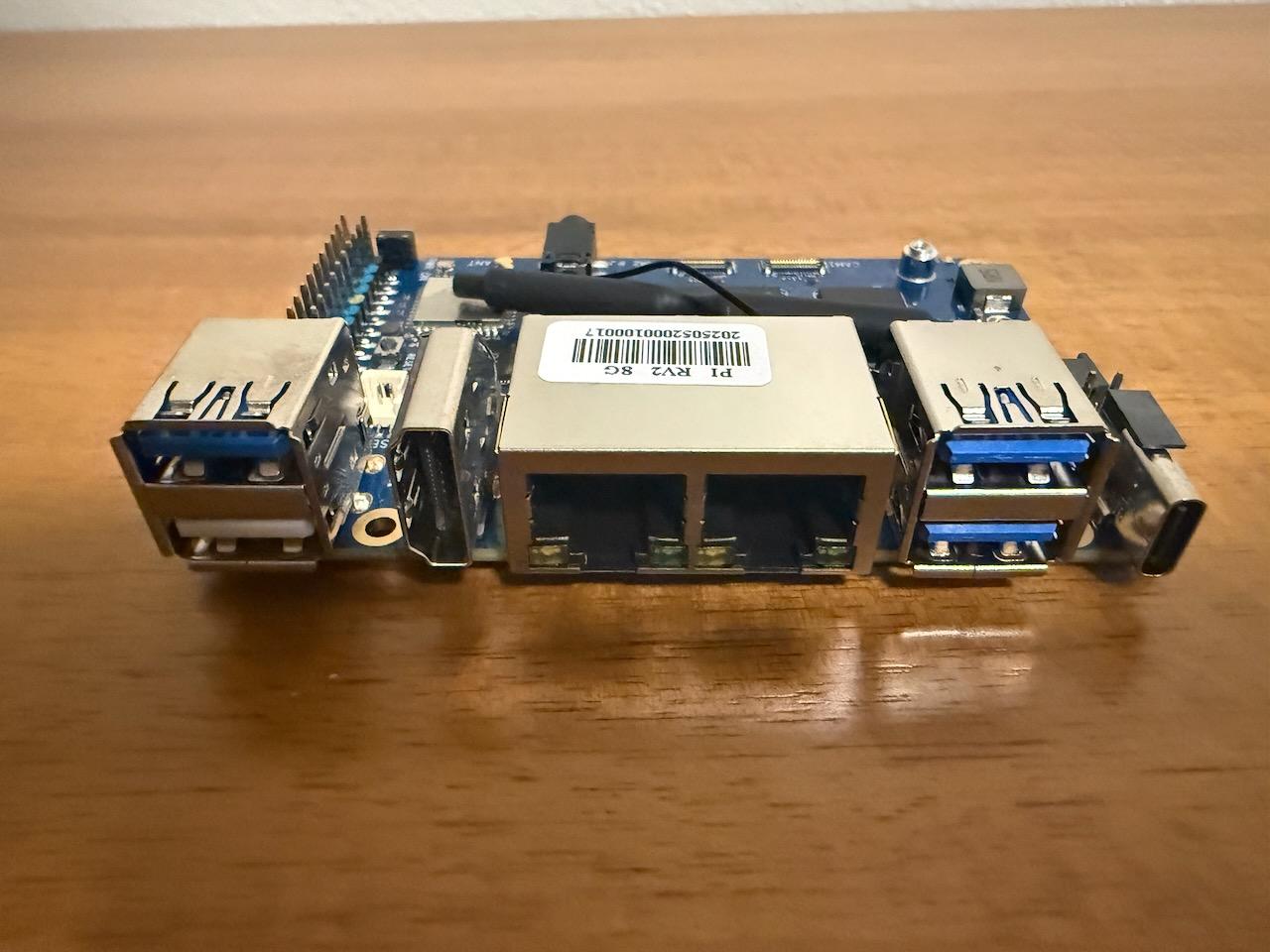

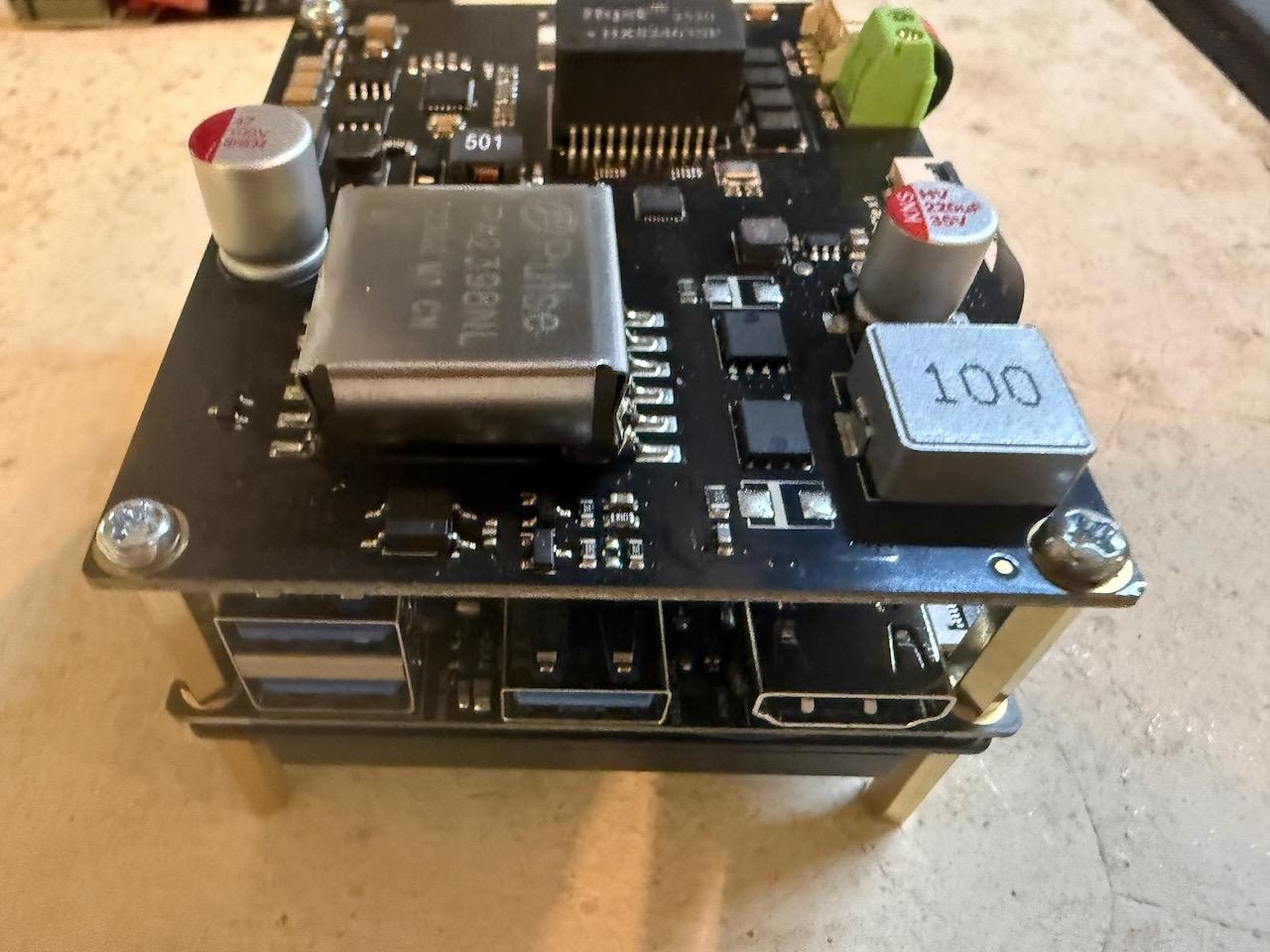

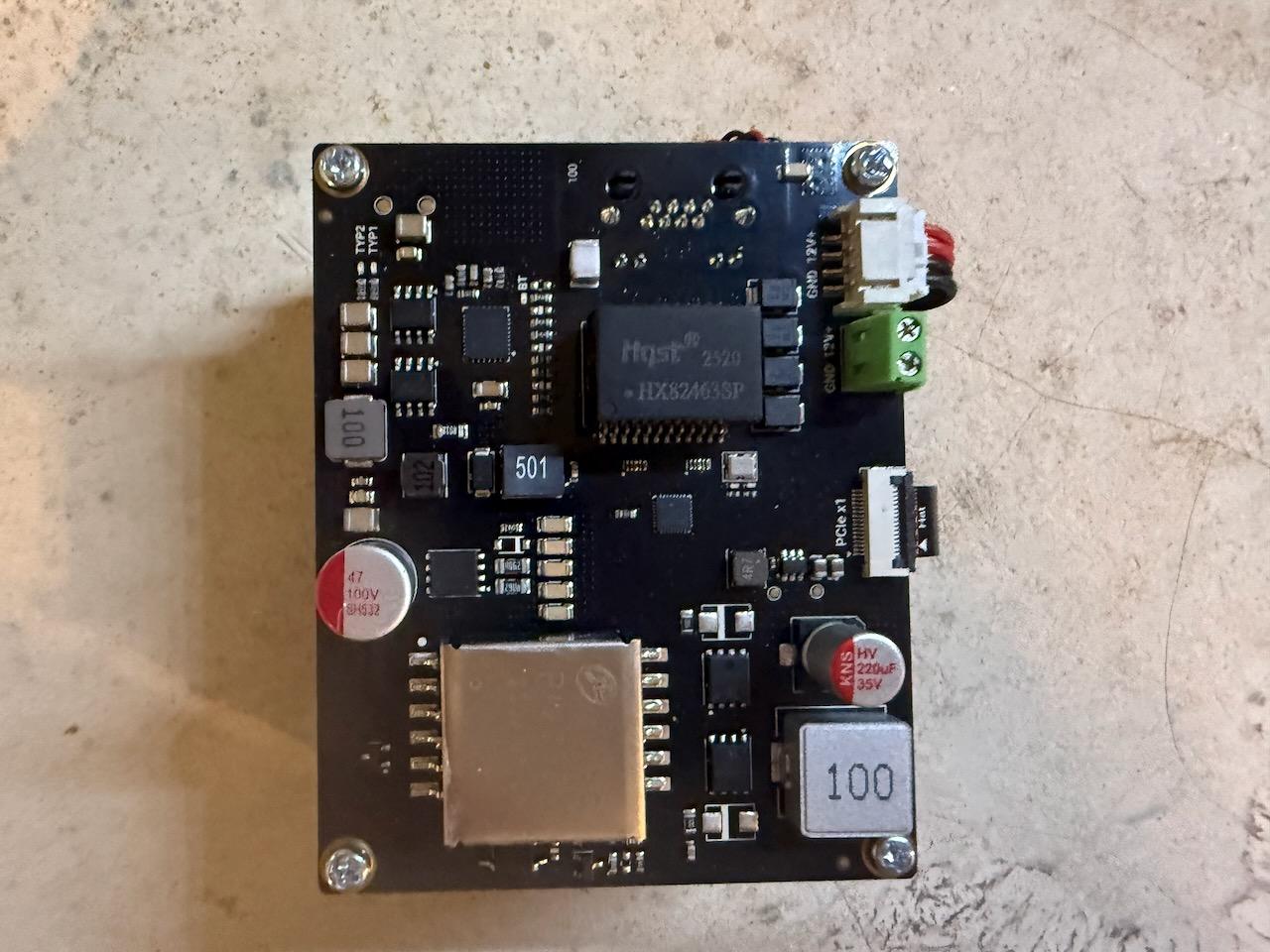

Horizon X3 CM compute module showing the CM4-compatible 200-pin connector

Horizon X3 CM installed on a carrier board with exposed components

Hardware Architecture: A Foundation Built on Yesterday's Technology

At the heart of the Horizon X3 CM lies the Sunrise X3 system-on-chip, featuring a quad-core ARM Cortex-A53 processor clocked at 1.5 GHz, paired with a single Cortex-R5 core for real-time tasks. The Cortex-A53, released by ARM in 2012, was already considered a low-power, efficiency-focused core at launch. By 2025 standards, it is ancient technology - predating even the Cortex-A55 by six years and the high-performance Cortex-A76 by eight years.

To put this in perspective: the Cortex-A53 was designed in an era when ARM was still competing against Intel Atom processors in tablets and smartphones. The microarchitecture lacks modern features like advanced branch prediction, sophisticated out-of-order execution, and the aggressive clock speeds found in contemporary ARM cores. It was never intended for computationally demanding workloads, instead optimizing for power efficiency in battery-powered devices.

The system includes 2GB or 4GB of RAM (our test unit had 4GB), eMMC storage options, and the typical suite of interfaces expected on a compute module: MIPI CSI for cameras, MIPI DSI for displays, USB 3.0, Gigabit Ethernet, and HDMI output. The physical form factor mimics the Raspberry Pi Compute Module 4's 200-pin board-to-board connector, allowing it to fit into existing CM4 carrier boards - at least in theory.

The BPU: Marketing Promise vs. Reality

The headline feature of the Horizon X3 CM is undoubtedly its Brain Processing Unit, marketed as providing 5 TOPS (trillion operations per second) of AI inference capability using Horizon's Bernoulli 2.0 architecture. The BPU is a dual-core dedicated neural processing unit fabricated on a 16nm process, designed specifically for edge AI applications in robotics and autonomous driving.

On paper, 5 TOPS sounds impressive for an edge device. The marketing materials emphasize the X3's ability to run AI models locally without cloud dependency, perform real-time object detection, enable autonomous navigation, and support various computer vision tasks. Horizon Robotics, founded in 2015 and focused primarily on automotive AI processors, positioned the Sunrise 3 chip as a way to bring their automotive-grade AI capabilities to the robotics and IoT markets.

In practice, the BPU's utility is severely constrained by several factors. First, the 5 TOPS figure assumes optimal utilization with models specifically optimized for the Bernoulli architecture. Second, the Cortex-A53 CPU cores create a significant bottleneck for any workload that cannot be entirely offloaded to the BPU. Third, and most critically, the toolchain and software ecosystem required to actually leverage the BPU is fragmented, poorly documented, and largely abandoned.

The Software Ecosystem: Abandonment and Fragmentation

Perhaps the most telling aspect of the Horizon X3 CM is the state of its software support. Horizon Robotics archived all their GitHub repositories, effectively abandoning public development and support. D-Robotics, which appears to be either a subsidiary or spin-off focused on the robotics market, has continued maintaining forks of some repositories, but the overall ecosystem feels scattered and undermaintained.

hobot_llm: An Exercise in Futility

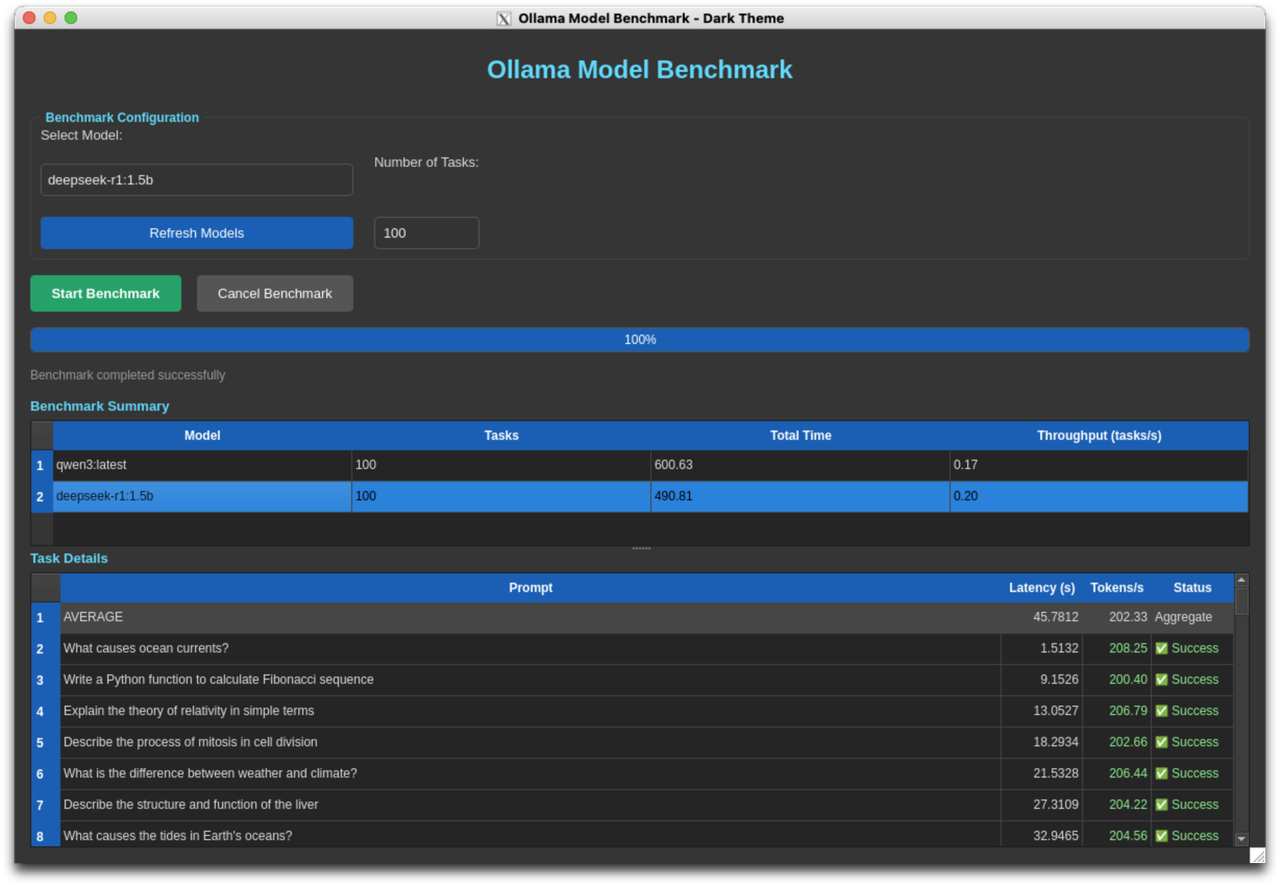

One of the more recent developments is hobot_llm, a project that attempts to run Large Language Models on the RDK X3 platform. Hosted at https://github.com/D-Robotics/hobot_llm, this ROS2 node promises to bring LLM capabilities to edge robotics applications. The reality is far less inspiring.

hobot_llm provides two interaction modes: a terminal-based chat interface and a ROS2 node that subscribes to text topics and publishes LLM responses. The system requires the 4GB RAM version of the RDK X3 and recommends increasing the BPU reserved memory to 1.7GB - leaving precious little memory for other tasks.

Users report that responses take 15-30 seconds to generate, and the quality of responses is described as "confusing and mostly unrelated to the query." This performance characteristic makes the system effectively useless for any real-time robotics application. A robot that takes 30 seconds to formulate a language-based response is not demonstrating intelligence; it's demonstrating the fundamental inadequacy of the platform.

The hobot_llm project exemplifies the broader problem with the X3 ecosystem: projects that look interesting in concept but fall apart under scrutiny, implemented on hardware that lacks the computational resources to make them practical, maintained by a fractured development community that can't provide consistent support.

D-Robotics vs. Horizon Robotics: Corporate Confusion

The relationship between Horizon Robotics and D-Robotics adds another layer of confusion for potential users. Horizon Robotics, the original creator of the Sunrise chips, has clearly shifted its focus to the automotive market, where margins are higher and customers are more willing to accept proprietary, closed-source solutions. The company's GitHub repositories were archived, signaling an end to community-focused development.

D-Robotics picked up the robotics development kit mantle, maintaining forks of key repositories like hobot_llm, hobot_dnn (the DNN inference framework), and the RDK model zoo. However, this continuation feels more like life support than active development. Commit frequencies are low, issues pile up without resolution, and the documentation remains fragmented across multiple sites (d-robotics.cc, developer.d-robotics.cc, github.com/D-Robotics, github.com/HorizonRDK).

For a potential user in 2025, this corporate structure raises immediate red flags. Who actually supports this platform? If you encounter a problem, where do you file an issue? If Horizon has abandoned the project and D-Robotics is merely keeping it alive, what is the long-term viability of building a product on this foundation?

The Bootstrap Nightmare: A System Designed to Frustrate

If the hardware limitations and software abandonment weren't enough to dissuade potential users, the actual process of getting a functioning Horizon X3 CM system should seal the case. We downloaded the latest Ubuntu 22.04-derived distribution from https://archive.d-robotics.cc/downloads/en/os_images/rdk_x3/rdk_os_3.0.3-2025-09-08/ and discovered a system configuration so broken and non-standard that it defies belief.

The Sudo Catastrophe

The most egregious issue: sudo doesn't work out of the box. Not because of a configuration error, but because critical system files are owned by the wrong user. The distribution ships with /usr/bin/sudo, /etc/sudoers, and related files owned by uid 1000 (the sunrise user) rather than root. This creates an impossible catch-22:

- You need root privileges to fix the file ownership

- sudo is the standard way to gain root privileges

- sudo won't function because of incorrect ownership

- You can't fix the ownership without root privileges

Traditional escape routes all fail. The root password is not set, so su doesn't work. pkexec requires polkit authentication. systemctl requires authentication for privileged operations. Even setting file capabilities (setcap) to grant specific privileges fails because the sunrise user lacks CAP_SETFCAP.

The workaround involves creating an /etc/rc.local script that runs at boot time as root to fix ownership of sudo binaries, sudoers files, and apt directories:

#!/bin/bash -e # Fix sudo binary ownership and permissions chown root:root /usr/bin/sudo chmod 4755 /usr/bin/sudo # Fix sudo plugins directory chown -R root:root /usr/lib/sudo/ # Fix sudoers configuration files chown root:root /etc/sudoers chmod 0440 /etc/sudoers chown -R root:root /etc/sudoers.d/ chmod 0755 /etc/sudoers.d/ chmod 0440 /etc/sudoers.d/* # Fix apt package manager directories mkdir -p /var/cache/apt/archives/partial mkdir -p /var/lib/apt/lists/partial chown -R root:root /var/lib/apt/lists chown _apt:root /var/lib/apt/lists/partial chmod 0700 /var/lib/apt/lists/partial chown -R root:root /var/cache/apt/archives chown _apt:root /var/cache/apt/archives/partial chmod 0700 /var/cache/apt/archives/partial exit 0

This is not a minor configuration quirk. This is a fundamental misunderstanding of Linux system security and standard practices. No competent distribution would ship with sudo broken in this manner. The fact that this made it into a release image dated September 2025 suggests either complete incompetence or absolute indifference to user experience.

Network Configuration Hell

The default network configuration assumes you're using the 192.168.1.0/24 subnet with a gateway at 192.168.1.1. If your network uses any other addressing scheme - as most enterprise networks, lab environments, and even many home networks do - you're in for a frustrating experience.

Changing the network configuration should be trivial: edit /etc/network/interfaces, update the IP address and gateway, reboot. Except the sunrise user lacks CAP_NET_ADMIN capability, so you can't use ip commands to modify network configuration on the fly. You can't use NetworkManager's command-line tools without authentication. You must edit the configuration files manually and reboot to apply changes.

Our journey to move the device from 192.168.1.10 to 10.1.1.135 involved:

- Accessing the device through a gateway system that could route to both networks

- Backing up /etc/network/interfaces

- Manually editing the static IP configuration

- Removing conflicting secondary IP configuration scripts

- Adding DNS servers (which weren't configured at all in the default image)

- Rebooting and hoping the configuration took

- Troubleshooting DNS resolution failures

- Editing /etc/systemd/resolved.conf to add nameservers

- Adding a systemd-resolved restart to /etc/rc.local

- Rebooting again

This process, which takes approximately 30 seconds on a properly configured Linux system, consumed hours on the Horizon X3 CM due to the broken permissions structure and missing default configurations.

Repository Roulette

The default APT repositories point to mirrors.tuna.tsinghua.edu.cn (a Chinese university mirror) and archive.sunrisepi.tech (which is frequently unreachable). For users outside China, these repositories are slow or inaccessible. The solution requires manually reconfiguring /etc/apt/sources.list to use official Ubuntu Ports mirrors:

deb http://ports.ubuntu.com/ubuntu-ports/ focal main restricted universe multiverse deb http://ports.ubuntu.com/ubuntu-ports/ focal-security main restricted universe multiverse deb http://ports.ubuntu.com/ubuntu-ports/ focal-updates main restricted universe multiverse

Again, this should be a non-issue. Modern distributions detect geographic location and configure appropriate mirrors automatically. The Horizon X3 CM requires manual intervention for basic package management functionality.

The Permission Structure Mystery

Beyond these specific issues lies a broader architectural decision that makes no sense: why are system directories owned by a non-root user? Running ls -ld on /etc, /usr/lib, and /var/lib/apt reveals they're owned by sunrise:sunrise rather than root:root. This violates fundamental Unix security principles and creates cascading problems throughout the system.

Was this an intentional design decision? If so, what was the rationale? Was it an accident that made it through quality assurance? The complete lack of documentation about this unusual setup suggests it's not intentional, yet it persists through multiple distribution releases.

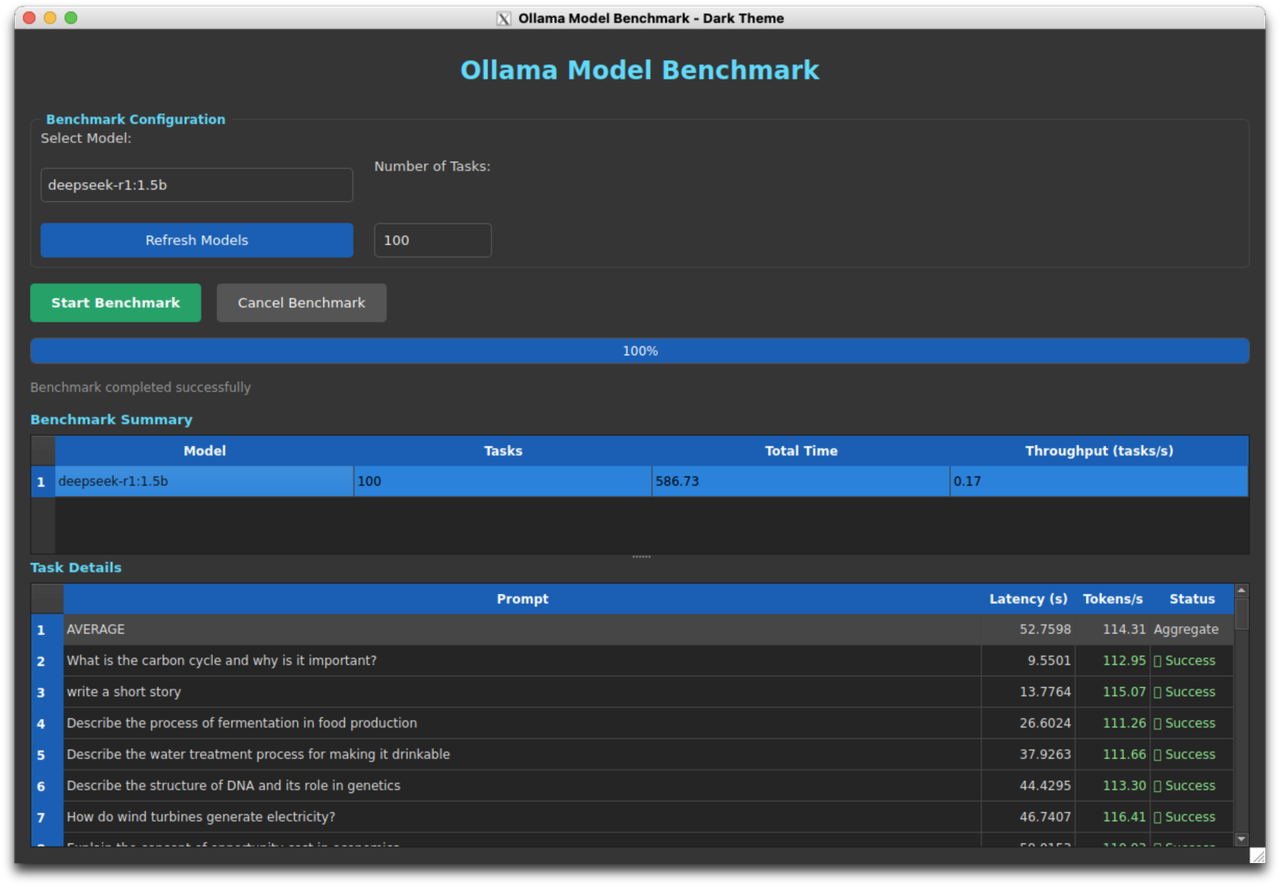

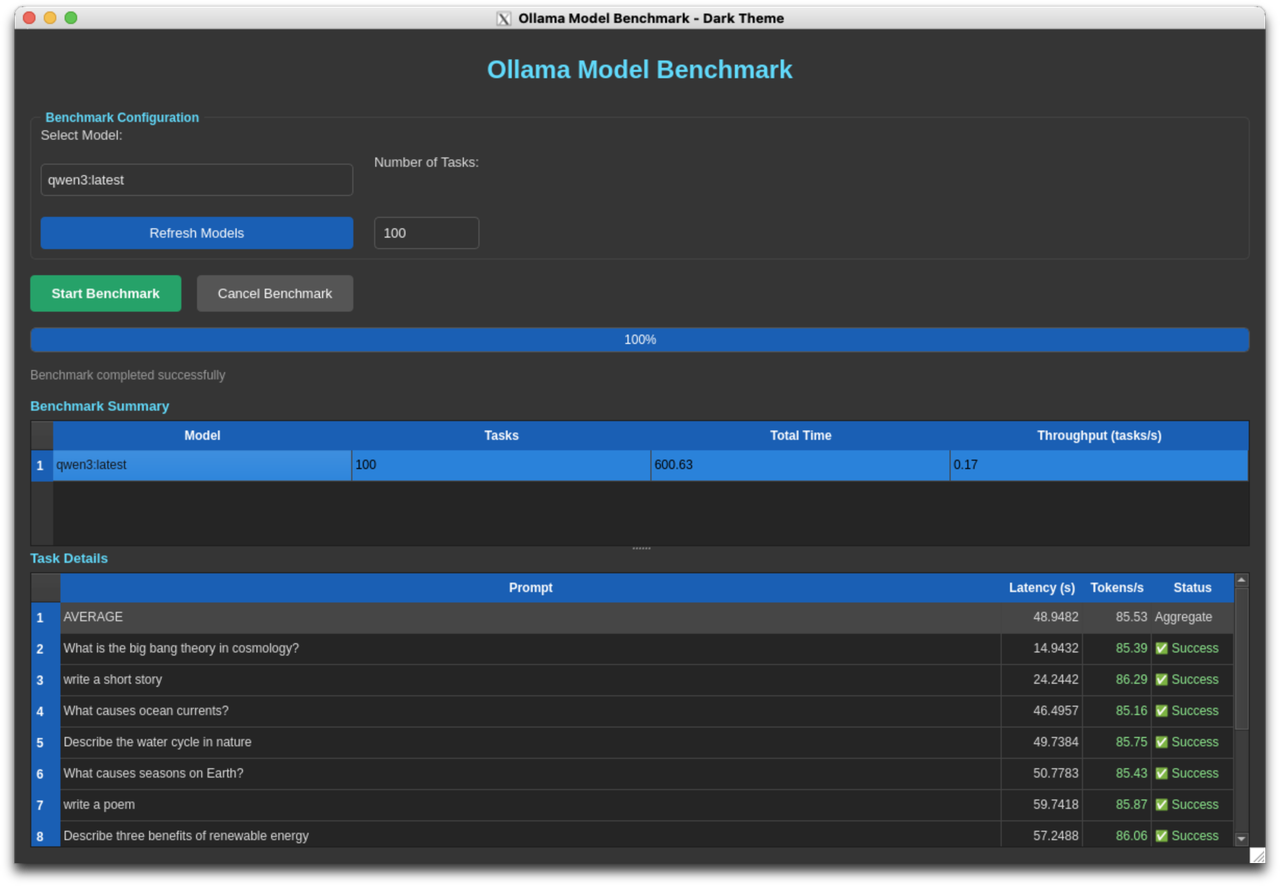

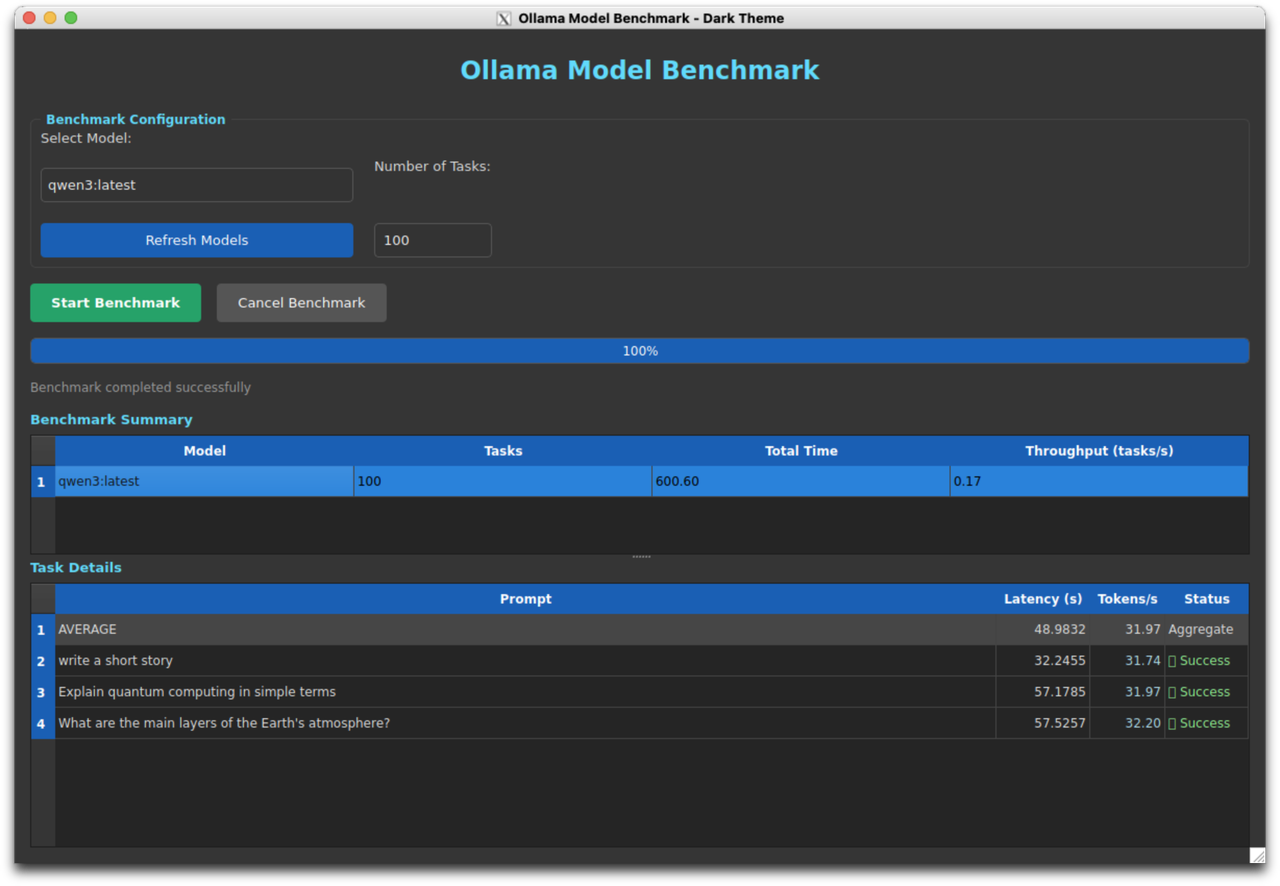

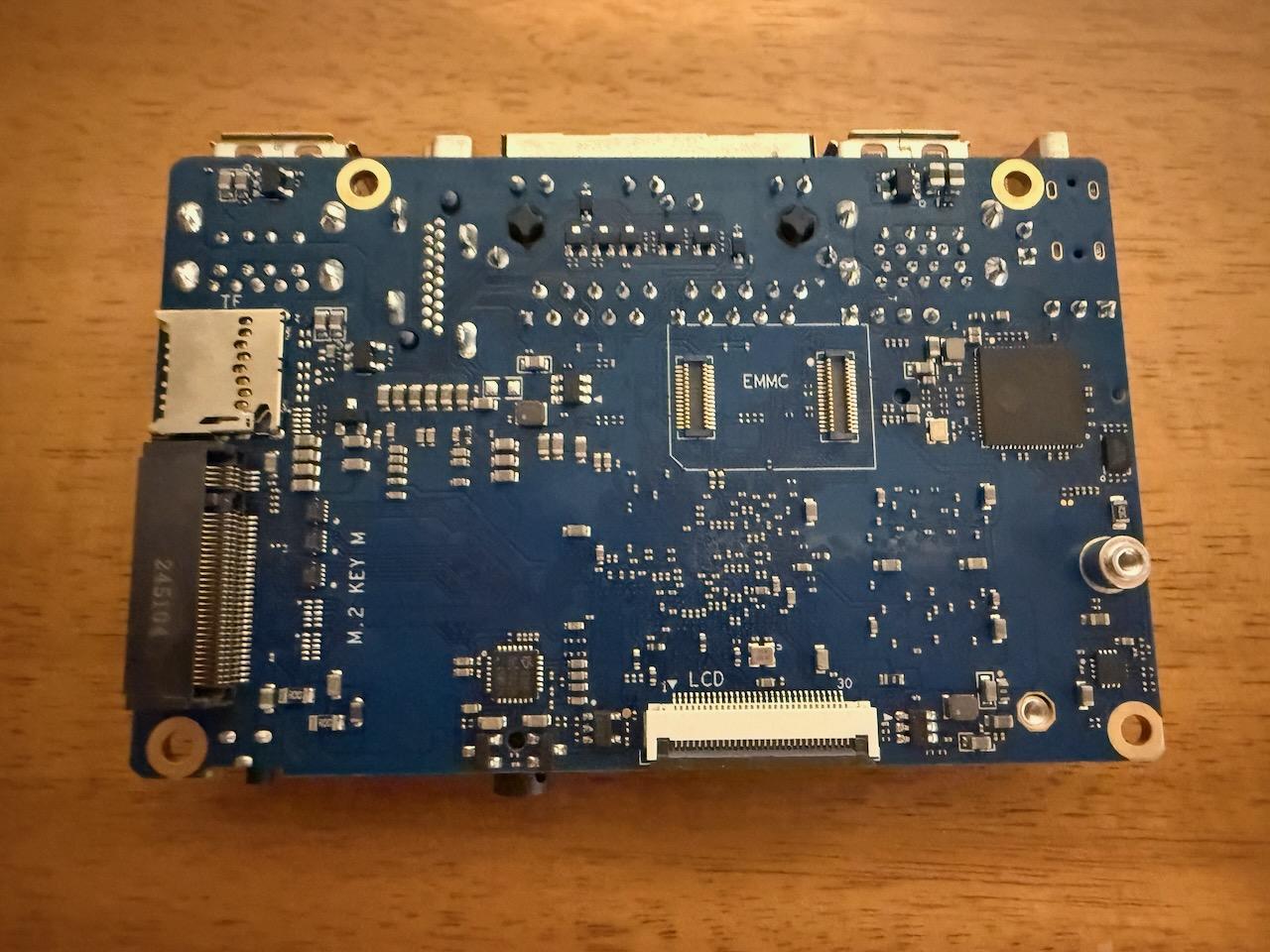

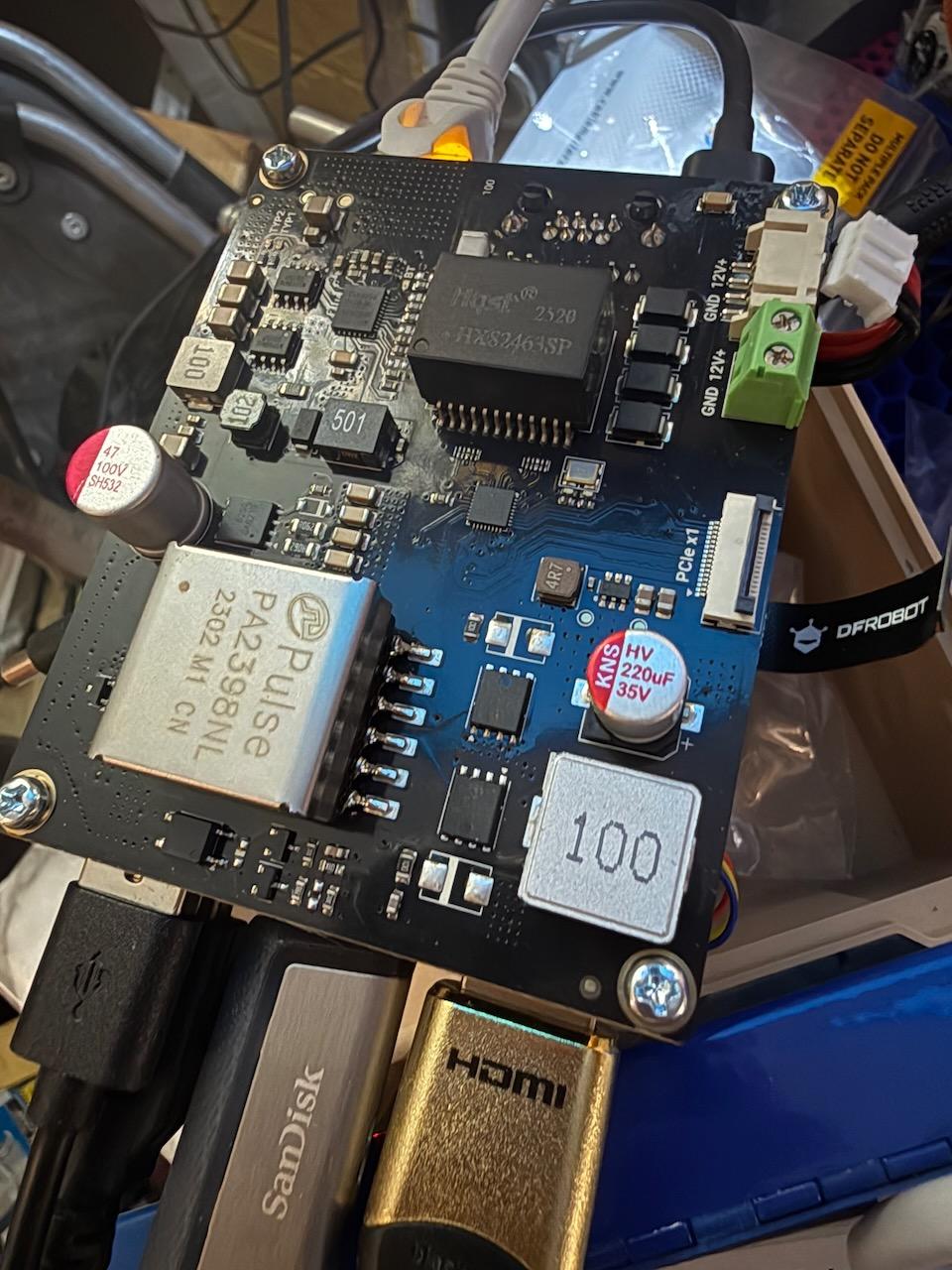

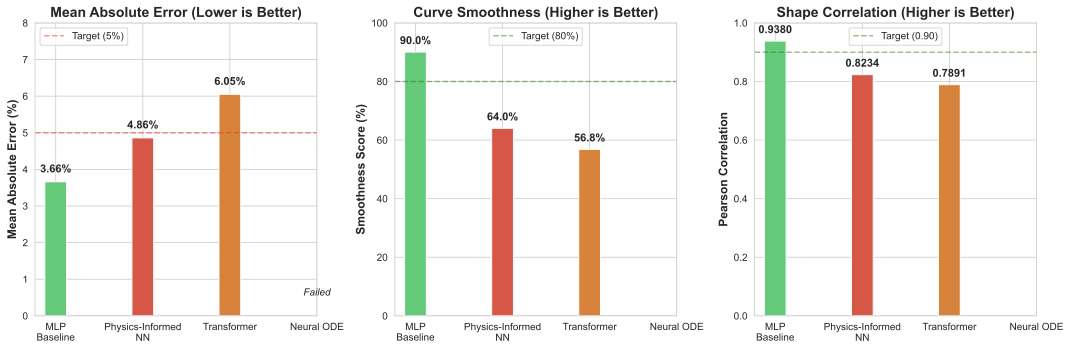

Performance Testing: Confirmation of Inadequacy

To quantitatively assess the Horizon X3 CM's performance, we ran our standard Rust compilation benchmark: building a complex ballistics simulation engine with numerous dependencies from clean state, three times, and averaging the results. This workload stresses CPU cores, memory bandwidth, and compiler performance - a representative real-world task for any development platform.

Benchmark Results

The Horizon X3 CM posted compilation times of:

- Run 1: 384.32 seconds (6 minutes 24 seconds)

- Run 2: 376.66 seconds (6 minutes 17 seconds)

- Run 3: 375.46 seconds (6 minutes 15 seconds)

- Average: 378.81 seconds (6 minutes 19 seconds)

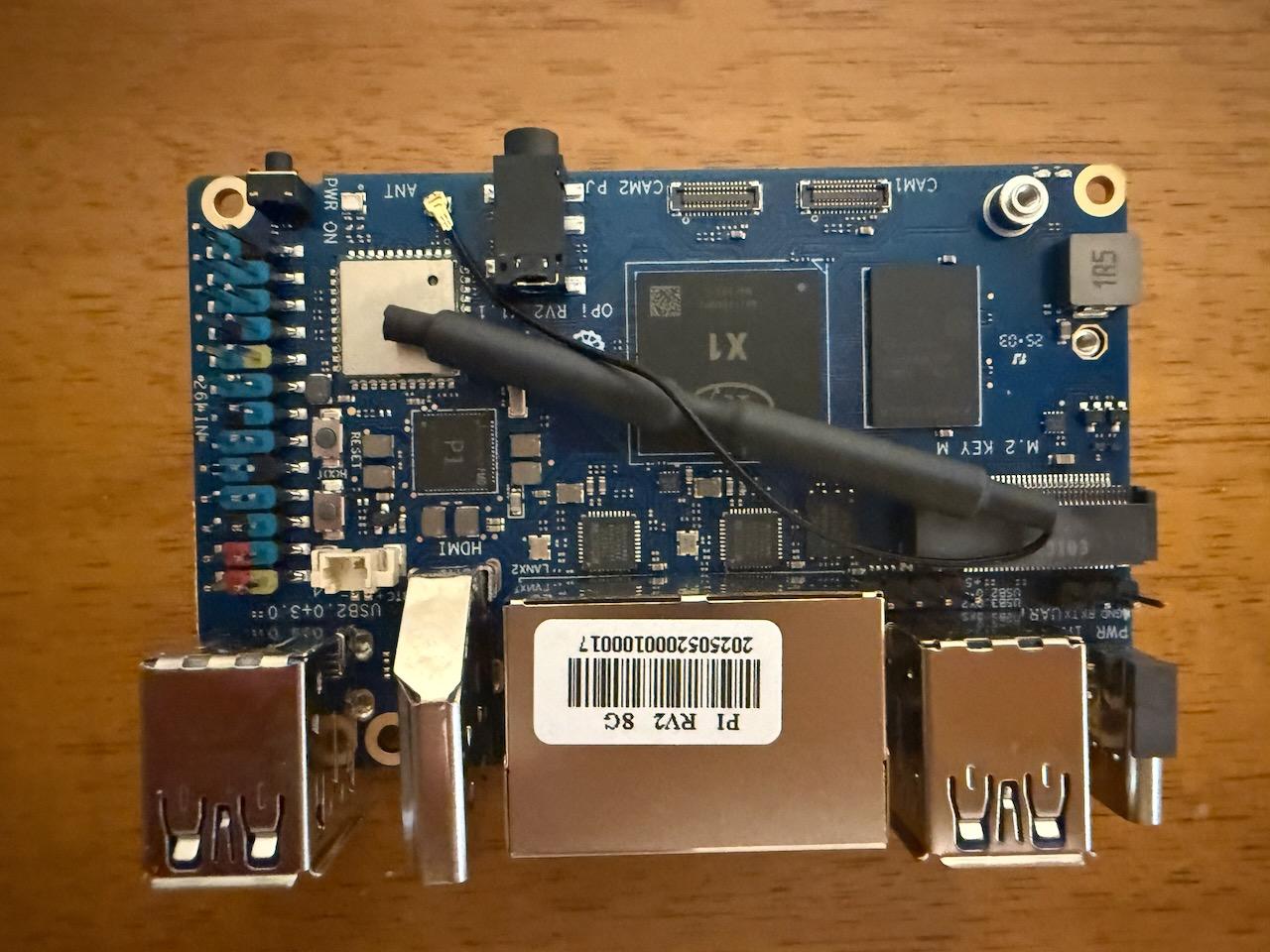

For context, here's how this compares to contemporary ARM and x86 single-board computers:

| System | Architecture | CPU | Cores | Average Time | vs. X3 CM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orange Pi 5 Max | ARM64 | Cortex-A55/A76 | 8 | 62.31s | 6.08x faster |

| Raspberry Pi CM5 | ARM64 | Cortex-A76 | 4 | 71.04s | 5.33x faster |

| LattePanda Iota | x86_64 | Intel N150 | 4 | 72.21s | 5.25x faster |

| Raspberry Pi 5 | ARM64 | Cortex-A76 | 4 | 76.65s | 4.94x faster |

| Horizon X3 CM | ARM64 | Cortex-A53 | 4 | 378.81s | 1.00x (baseline) |

| Orange Pi RV2 | RISC-V | Ky X1 | 8 | 650.60s | 1.72x slower |

The Horizon X3 CM is approximately five times slower than the Raspberry Pi 5, despite both boards having four cores. This dramatic performance gap is explained by the generational difference in ARM core architecture: the Cortex-A76 in the Pi 5 represents eight years of microarchitectural advancement over the A53, with wider execution units, better branch prediction, higher clock speeds, and more sophisticated memory hierarchies.

The only platform slower than the X3 CM in our testing was the Orange Pi RV2, which uses an experimental RISC-V processor with an immature compiler toolchain. The fact that an established ARM platform with a mature software ecosystem performs only 1.72x better than a bleeding-edge RISC-V platform speaks volumes about the X3's inadequacy.

Geekbench 6 Results: Industry-Standard Confirmation

To complement our real-world compilation benchmarks, we also ran Geekbench 6 - an industry-standard synthetic benchmark that measures CPU performance across a variety of workloads including cryptography, image processing, machine learning, and general computation. The results reinforce and quantify just how far behind the Horizon X3 CM falls compared to modern alternatives.

Horizon X3 CM Geekbench 6 Scores:

- Single-Core Score: 127

- Multi-Core Score: 379

- Geekbench Link: https://browser.geekbench.com/v6/cpu/14816041

For context, here's how this compares to other single-board computers running Geekbench 6:

| System | CPU | Single-Core | Multi-Core | vs. X3 Single | vs. X3 Multi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orange Pi 5 Max | Cortex-A55/A76 | 743 | 2,792 | 5.85x faster | 7.37x faster |

| Raspberry Pi 5 | Cortex-A76 | 764-774 | 1,588-1,604 | 6.01-6.09x faster | 4.19-4.23x faster |

| Raspberry Pi 5 (OC) | Cortex-A76 | 837 | 1,711 | 6.59x faster | 4.51x faster |

| Horizon X3 CM | Cortex-A53 | 127 | 379 | 1.00x (baseline) | 1.00x (baseline) |

The Geekbench results align remarkably well with our compilation benchmarks, confirming that the X3 CM's poor performance isn't specific to one workload but represents a fundamental computational deficit across all task types.

A single-core score of 127 is abysmal by 2025 standards. To put this in perspective, the iPhone 6s from 2015 scored around 140 in single-core Geekbench 6 tests. The Horizon X3 CM, released in 2021-2022, delivers performance comparable to a decade-old smartphone processor.

The multi-core score of 379 shows that the X3 fails to effectively leverage its four cores. Despite having the same core count as the Raspberry Pi 5, the X3 scores less than one-quarter of the Pi 5's multi-core performance. The Orange Pi 5 Max, with its eight cores (four A76 + four A55), absolutely destroys the X3 with 7.37x better multi-core performance.

The Geekbench individual test scores reveal specific weaknesses:

- Navigation tasks: 282 single-core (embarrassingly slow for robotics applications requiring path planning)

- Clang compilation: 208 single-core (confirming our real-world compilation benchmark findings)

- HTML5 Browser: 180 single-core (even web-based robot control interfaces would lag)

- PDF Rendering: 200 single-core, 797 multi-core (document processing would crawl)

These synthetic benchmarks might seem academic, but they translate directly to real-world robotics performance. The navigation score predicts poor path planning performance. The Clang score explains the painful compilation times. The HTML5 browser score means even accessing web-based configuration interfaces will be sluggish. Every aspect of development and deployment on the X3 CM will feel slow because the processor is fundamentally inadequate.

What This Means for Real Workloads

The compilation benchmark translates directly to real-world robotics and AI development scenarios:

Development iteration time: Compiling ROS2 packages, building custom nodes, and testing changes takes five times longer than on a Raspberry Pi 5. A developer waiting 20 minutes for a build on the Pi 5 will wait 100 minutes on the X3 CM.

AI model training: While the BPU handles inference, any model training, data preprocessing, or optimization work runs on the Cortex-A53 cores at a glacial pace.

Computer vision processing: Pre-BPU image processing, post-BPU result processing, and any vision algorithms not optimized for the Bernoulli architecture will execute slowly.

Multi-tasking performance: Running ROS2, sensor drivers, motion controllers, and application logic simultaneously will strain the limited CPU resources. The cores will spend more time context switching than doing useful work.

The AI Promise: Hollow Marketing

Let's return to the central premise of the Horizon X3 CM: it's an AI-focused robotics platform with a dedicated Brain Processing Unit providing 5 TOPS of inference capability. Does this specialization justify the platform's shortcomings?

The answer is a resounding no.

First, 5 TOPS is not impressive by 2025 standards. The Google Coral TPU provides 4 TOPS in a USB dongle costing under $60. The NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano provides 40 TOPS. Even smartphone SoCs like the Apple A17 Pro deliver over 35 TOPS. The Horizon X3's 5 TOPS might have been notable in 2020 when the chip was announced, but it's thoroughly uncompetitive five years later.

Second, the BPU's usefulness is limited by the proprietary toolchain and model conversion requirements. You can't simply take a TensorFlow or PyTorch model and run it on the BPU. It must be converted using Horizon's tools, quantized to specific formats the Bernoulli architecture supports, and optimized for the dual-core BPU's execution model. The documentation for this process is scattered, incomplete, and assumes familiarity with Horizon's automotive-focused development flow.

Third, the weak Cortex-A53 cores undermine any AI acceleration advantage. If your application spends 70% of its time in AI inference and 30% in CPU-bound tasks, accelerating the inference to near-zero still leaves you with performance dominated by the slow CPU. The system is only as fast as its slowest component, and the CPU is very slow.

Fourth, the ecosystem lock-in is severe. Code written for the Horizon BPU doesn't port to other platforms. Models optimized for Bernoulli architecture require re-optimization for other accelerators. Investing development time in Horizon-specific tooling is investing in a dead-end technology with an uncertain future.

Compare this to the Raspberry Pi ecosystem, where you can add AI acceleration through well-supported options like the Coral TPU, Intel Neural Compute Stick, or Hailo-8 accelerator. These solutions work across the Pi 4, Pi 5, and other platforms, with mature Python APIs, extensive documentation, and active communities. The development you do with these accelerators transfers to other projects and platforms.

Documentation: Scarce and Scattered

Throughout our evaluation of the Horizon X3 CM, a consistent theme emerged: finding documentation for any task ranged from difficult to impossible. Want to understand the BPU's capabilities? The information is spread across d-robotics.cc, developer.d-robotics.cc, archived Horizon Robotics pages, and forums in both English and Chinese.

Looking for example code? Some repositories on GitHub have examples, but they assume familiarity with Horizon's model conversion tools. The tools themselves have documentation, but it's automotive-focused and doesn't translate well to robotics applications.

Need help troubleshooting a problem? The forums are sparsely populated, with many questions unanswered. The most reliable source of information is reverse-engineering what other users have done and hoping it works on your hardware revision.

This stands in stark contrast to the Raspberry Pi ecosystem, where every sensor, every module, every software package has multiple tutorials, forums full of discussions, YouTube videos, and GitHub repositories with example code. The Pi's ubiquity means that any problem you encounter has likely been solved multiple times by others.

The YouTube Deception

It's worth addressing the several YouTube videos that demonstrate the Horizon X3 running robotics applications, performing object detection, and controlling robot platforms. These videos create an impression that the X3 is a viable robotics platform. They're not technically dishonest - the hardware can do these things - but they omit the critical context that makes the X3 a poor choice.

These demonstrations typically show:

- Custom-built systems where someone has already overcome the configuration hurdles

- Specific AI models that have been painstakingly optimized for the BPU

- Applications that carefully avoid the CPU bottlenecks

- No comparisons to how the same task performs on alternative platforms

- No discussion of development time, tool chain difficulties, or ecosystem limitations

What they don't show is the hours spent fixing sudo, configuring networks, battling documentation gaps, and waiting for slow compilation. They don't mention that achieving the same functionality on a Raspberry Pi 5 with a Coral TPU would be faster to develop, more performant, better documented, and more maintainable.

The YouTube demonstrations are real, but they represent the absolute best case: experienced developers who've mastered the platform's quirks showing carefully crafted demos. They do not represent the typical user experience.

Who Is This For? (No One)

Attempting to identify the target audience for the Horizon X3 CM reveals its fundamental problem: there isn't a clear use case where it's the best choice.

Beginners: Absolutely not. The broken sudo, network configuration challenges, scattered documentation, and proprietary toolchain create insurmountable barriers for someone learning robotics development. A beginner choosing the X3 will spend 90% of their time fighting the platform and 10% actually learning robotics.

Intermediate developers: Still no. Someone with Linux experience and basic robotics knowledge will be frustrated by the X3's limitations. They have the skills to configure the system, but they'll quickly realize they're wasting time on a platform that's slower, less documented, and more restrictive than alternatives.

Advanced developers: Why would they choose this? An advanced developer evaluating SBC options will immediately recognize the Cortex-A53's limitations, the proprietary BPU lock-in, and the ecosystem fragmentation. They'll choose a Raspberry Pi with modular acceleration, or an NVIDIA Jetson if they need serious AI performance, or an x86 platform if they need raw CPU power.

Automotive developers: This is Horizon's actual target market, but they're not using the off-the-shelf RDK X3 boards. They're integrating the Sunrise chips into custom hardware with proprietary board support packages, automotive-grade Linux distributions, and Horizon's professional support contracts.

The hobbyist robotics market that the RDK X3 ostensibly targets is better served by literally any other option. The Raspberry Pi ecosystem offers superior hardware, vastly better documentation, more active communities, and modular expandability. Even the aging Raspberry Pi 4 is arguably a better choice than the X3 CM for most robotics projects.

Conclusion: An Irrelevant Platform in 2025

The Horizon X3 CM represents a failed experiment in bringing automotive AI technology to the robotics hobbyist market. The hardware is built on outdated ARM cores that were unimpressive when they launched in 2012 and are thoroughly inadequate in 2025. The AI acceleration, while technically present, is hamstrung by weak CPUs, proprietary tooling, and an abandoned software ecosystem. The software distributions ship broken, requiring extensive manual fixes to achieve basic functionality.

Our performance testing confirms what the specifications suggest: the X3 CM is approximately five times slower than a current-generation Raspberry Pi 5 for CPU-bound workloads. Both our real-world Rust compilation benchmarks and industry-standard Geekbench 6 synthetic tests show consistent results - the X3 CM delivers single-core performance 6x slower and multi-core performance 4-7x slower than modern competition. The BPU's 5 TOPS of AI acceleration cannot compensate for this massive performance deficit, and the proprietary nature of the Bernoulli architecture creates vendor lock-in without providing compelling advantages.

The documentation situation is dire, with information scattered across multiple sites in multiple languages, many links pointing to archived or defunct resources. The corporate structure - Horizon Robotics abandoning public development while D-Robotics maintains forks - raises serious questions about long-term support and viability.

For anyone considering robotics development in 2025, the recommendation is clear: avoid the Horizon X3 CM. If you're a beginner, start with a Raspberry Pi 5 - you'll have vastly more resources available, a supportive community, and hardware that won't frustrate you at every turn. If you're an intermediate or advanced developer, the Pi 5 with optional AI acceleration (Coral TPU, Hailo-8) will give you more flexibility, better performance, and a lower total cost of ownership. If you need serious AI horsepower, look at NVIDIA's Jetson line, which provides professional-grade AI acceleration with mature tooling and extensive documentation.

The Horizon X3 CM is a platform that perhaps made sense when announced in 2020-2021, competing against the Raspberry Pi 4 and targeting a market that was just beginning to explore edge AI. But time has not been kind. The ARM cores have aged poorly, the software ecosystem never achieved critical mass, and the corporate support has evaporated. In 2025, choosing the Horizon X3 CM for a new robotics project is choosing to fight your tools rather than build your robot.

The most damning evidence is this: even the Orange Pi RV2, running a brand-new RISC-V processor with an immature compiler toolchain and experimental software stack, is only 1.72x slower than the X3 CM. An experimental architecture with bleeding-edge hardware and alpha-quality software performs almost as well as an established ARM platform with supposedly mature tooling. Both our real-world compilation benchmarks and Geekbench 6 synthetic tests confirm the X3 CM's performance is comparable to a decade-old iPhone 6s processor - a smartphone chip from 2015 outperforms this 2021-2022 era robotics development platform. This speaks volumes about just how underpowered and poorly optimized the Horizon X3 CM truly is.

Save yourself the frustration. Build your robot on a platform that respects your time, provides the tools you need, and has a future. The Raspberry Pi ecosystem is the obvious choice, but almost any alternative - even commodity x86 mini-PCs - would serve you better than the Horizon X3 CM.

Specifications Summary

For reference, here are the complete specifications of the Horizon X3 CM:

Processor:

- Sunrise X3 SoC (16nm process)

- Quad-core ARM Cortex-A53 @ 1.5 GHz

- Single ARM Cortex-R5 core

- Dual-core Bernoulli 2.0 BPU (5 TOPS AI inference)

Memory & Storage:

- 2GB or 4GB LPDDR4 RAM

- 8GB/16GB/32GB eMMC options

- MicroSD card slot

Video:

- 4K@60fps H.264/H.265 encoding

- 4K@60fps decoding

- HDMI 2.0 output

Interfaces:

- 2x MIPI CSI (camera input)

- 1x MIPI DSI (display output)

- 2x USB 3.0

- Gigabit Ethernet

- 40-pin GPIO header

- I2C, SPI, UART, PWM

Physical:

- 200-pin board-to-board connector (CM4-compatible)

- Dimensions: 55mm x 40mm

Software:

- Ubuntu 20.04/22.04 based distributions

- ROS2 support (in theory)

- Horizon OpenExplorer development tools

Benchmark Performance:

- Rust compilation: 378.81 seconds average (5x slower than Raspberry Pi 5)

- Geekbench 6 Single-Core: 127 (6x slower than Raspberry Pi 5)

- Geekbench 6 Multi-Core: 379 (4-7x slower than modern ARM SBCs)

- Geekbench Link: https://browser.geekbench.com/v6/cpu/14816041

- Relative performance: 1.72x faster than experimental RISC-V, 6x slower than modern ARM

- Performance comparable to iPhone 6s (2015) in single-core workloads

Recommendation: Avoid. Use Raspberry Pi 5 or equivalent instead.

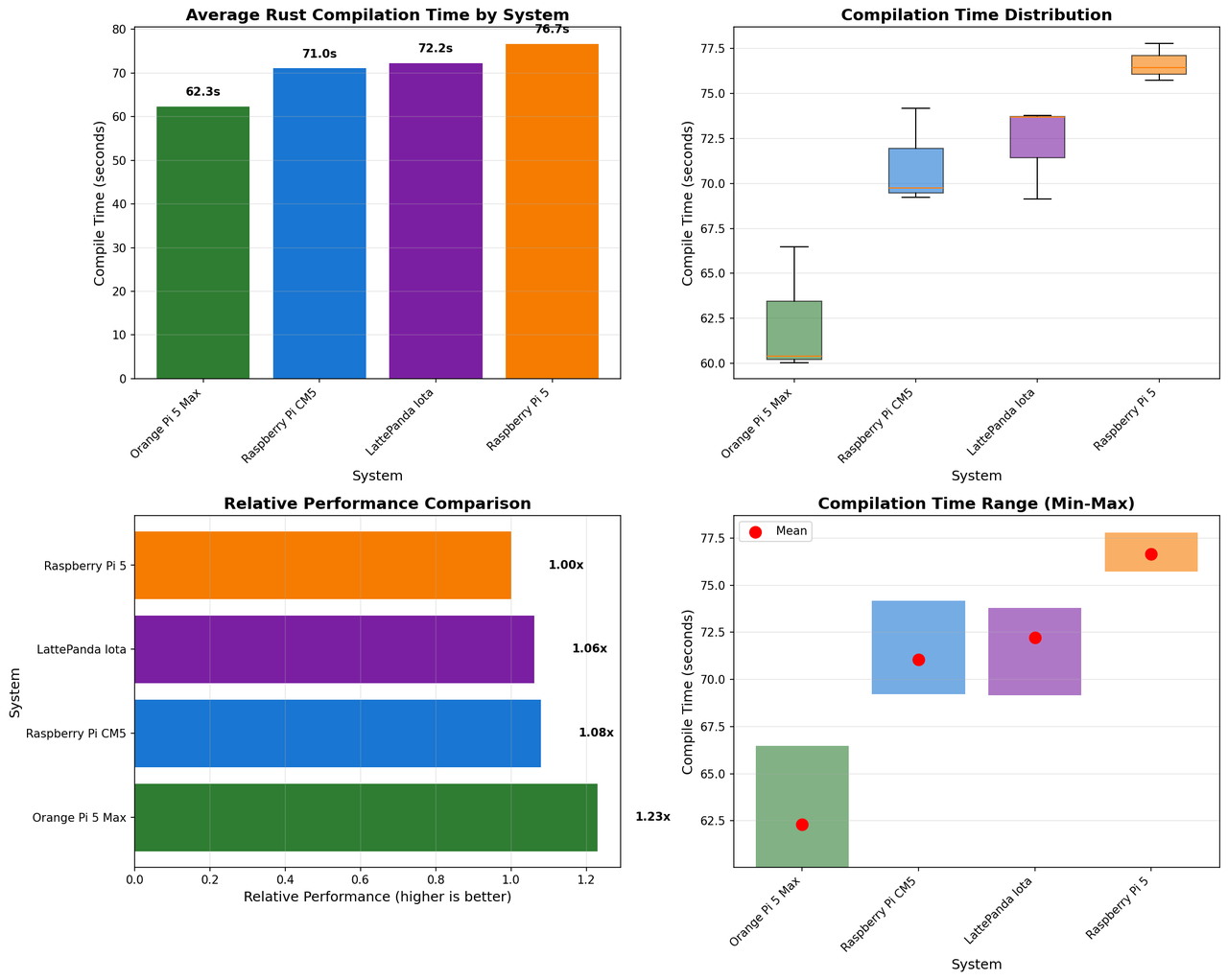

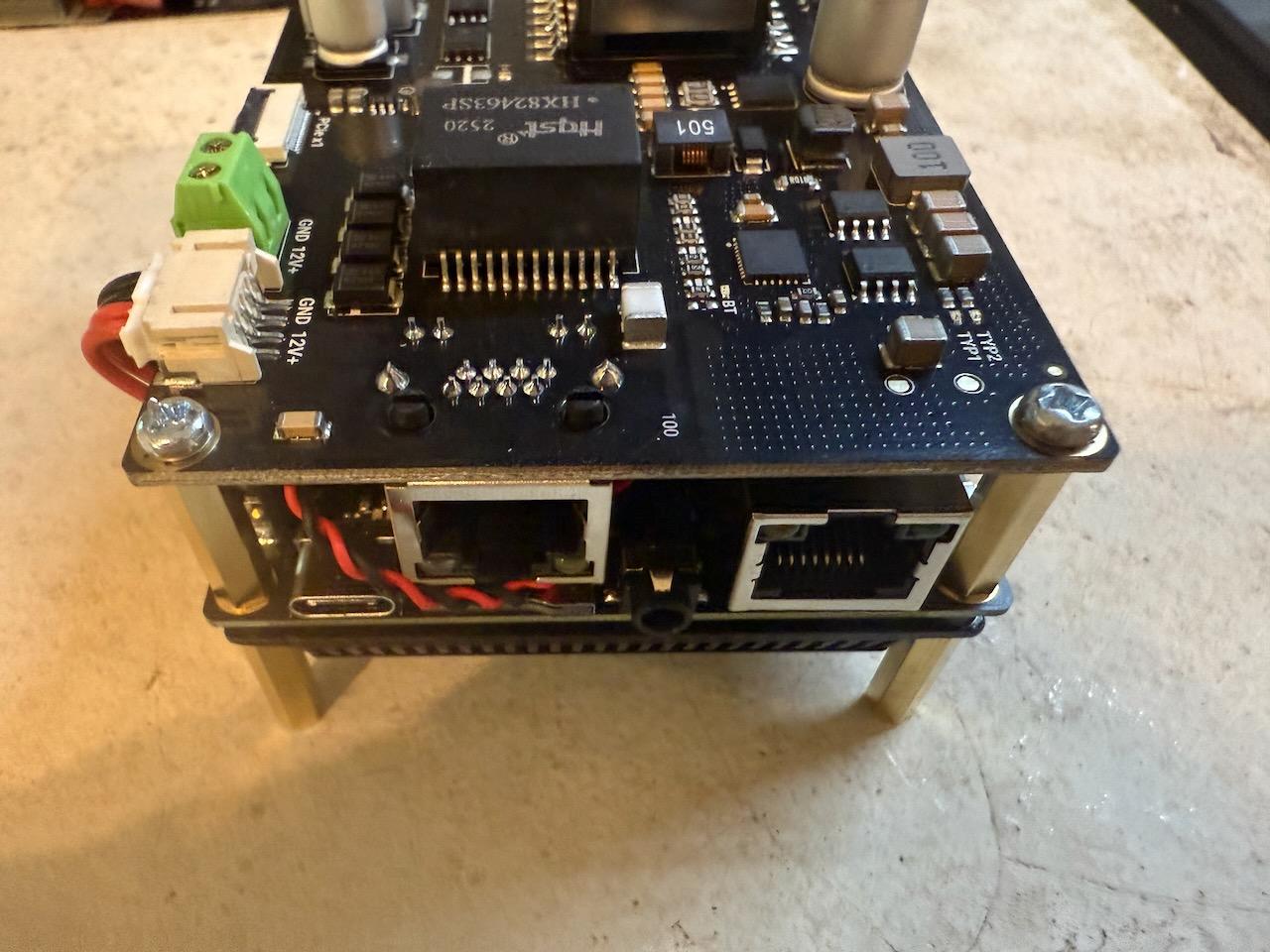

The LattePanda IOTA booting up - x86 performance in a compact form factor

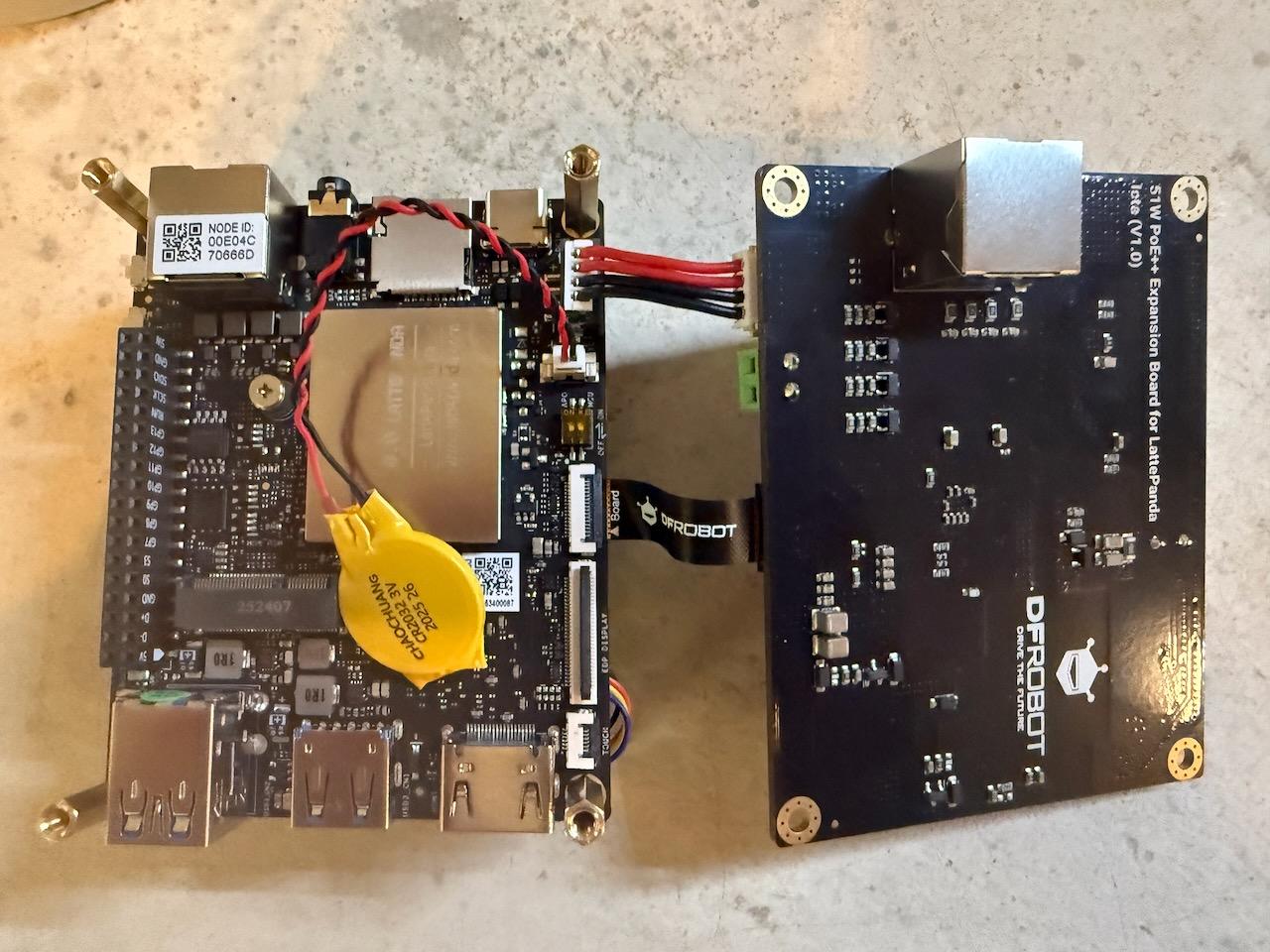

The LattePanda IOTA booting up - x86 performance in a compact form factor The LattePanda IOTA with PoE expansion board - compact yet feature-rich

The LattePanda IOTA with PoE expansion board - compact yet feature-rich Close-up showing the RP2040 co-processor, PoE module, and connectivity options

Close-up showing the RP2040 co-processor, PoE module, and connectivity options

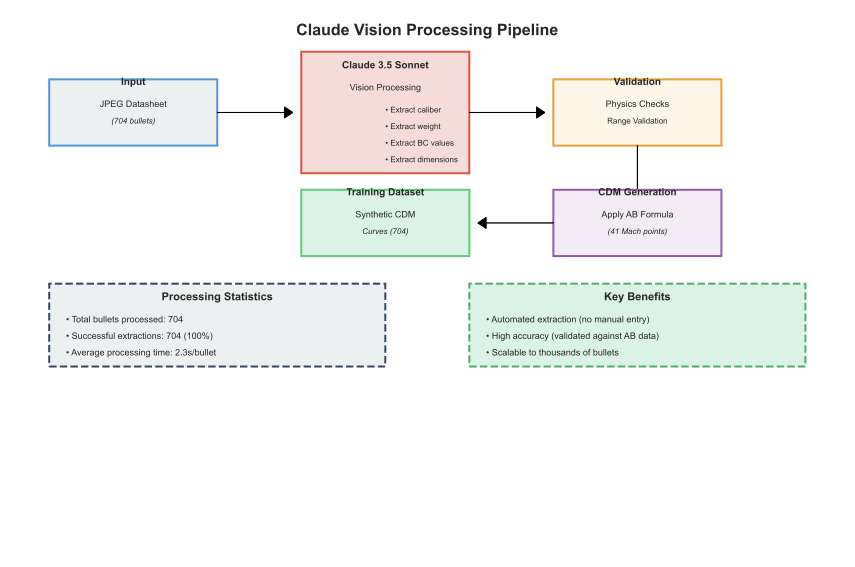

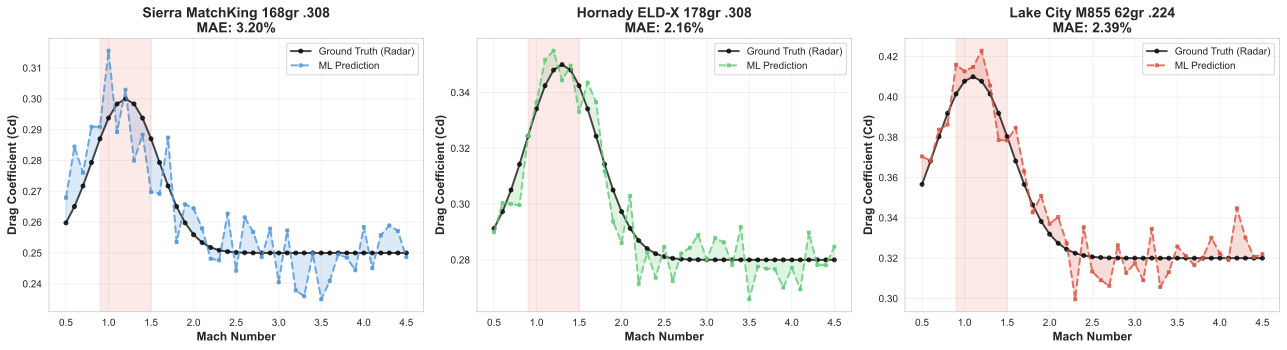

Figure 7: Example predicted CDM curves compared to ground truth measurements

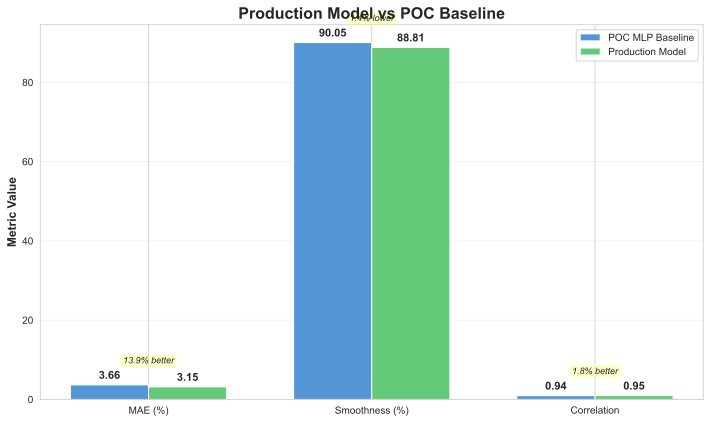

Figure 7: Example predicted CDM curves compared to ground truth measurements Figure 8: Production inference performance metrics across different batch sizes

Figure 8: Production inference performance metrics across different batch sizes