There's something deeply satisfying about running code on vintage hardware. The blinking cursor, the deliberate pace of execution, the direct connection between your keystrokes and the machine's response. The RetroShield by Erturk Kocalar brings this experience to modern makers by allowing real vintage CPUs like the Zilog Z80 to run on Arduino boards. But what if you could experience that same feeling directly in your web browser?

That's exactly what I set out to build: a complete Z80 emulator that runs RetroShield firmware in WebAssembly, complete with authentic CRT visual effects and support for multiple programming language interpreters.

Try It Now

Select a ROM below and click "Load ROM" to start. Click on the terminal to focus it, then type to interact with the interpreter.

INTEGER X then X = 42 then WRITE(*,*) X

ROM Information

Select a ROM above to load it into the emulator.

The RetroShield Platform

Before diving into the emulator, it's worth understanding what makes the RetroShield special. Unlike software emulators that simulate a CPU in code, the RetroShield uses a real vintage microprocessor. The Z80 variant features an actual Zilog Z80 chip running at its native speed, connected to an Arduino Mega or Teensy that provides:

- Memory emulation: The Arduino's SRAM serves as the Z80's RAM, while program code is stored in the Arduino's flash memory

- I/O peripherals: Serial communication, typically through an emulated MC6850 ACIA or Intel 8251 USART

- Clock generation: The Arduino provides the clock signal to the Z80

This hybrid approach means you get authentic Z80 behavior - every timing quirk, every undocumented opcode - while still having the convenience of USB connectivity and easy program loading.

The RetroShield is open source hardware and available on Tindie. For larger programs, the Teensy adapter expands available RAM from about 4KB to 256KB.

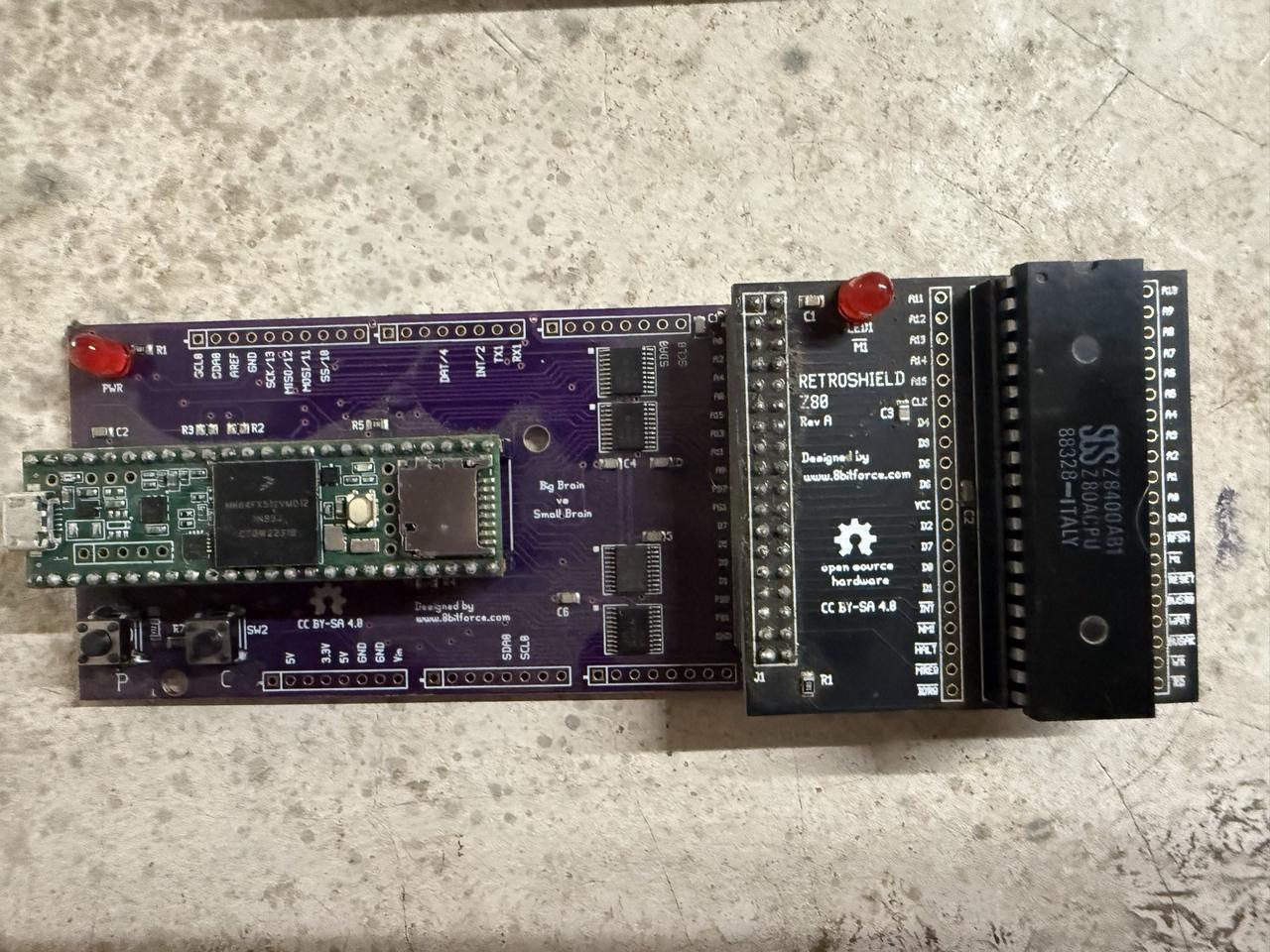

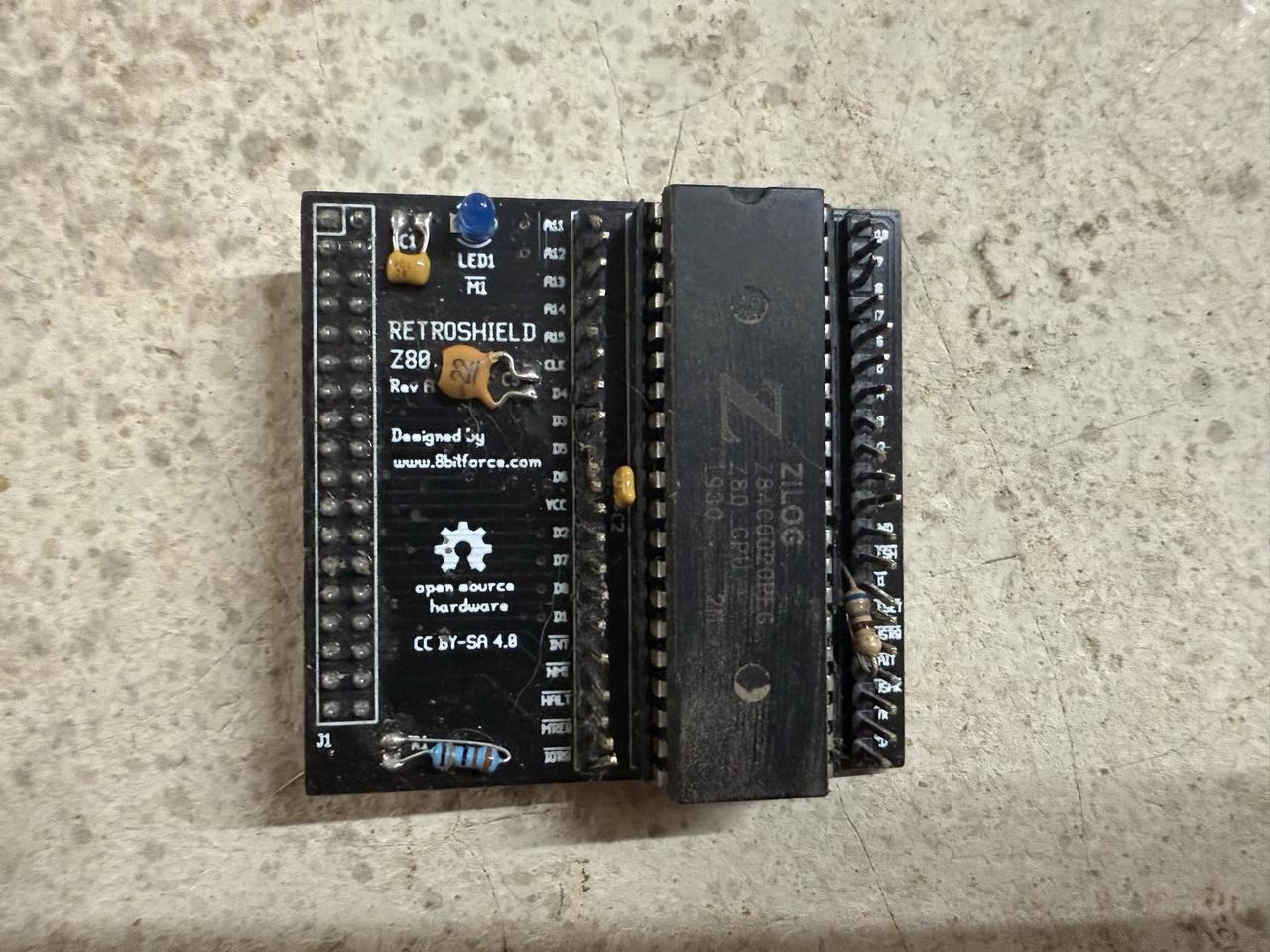

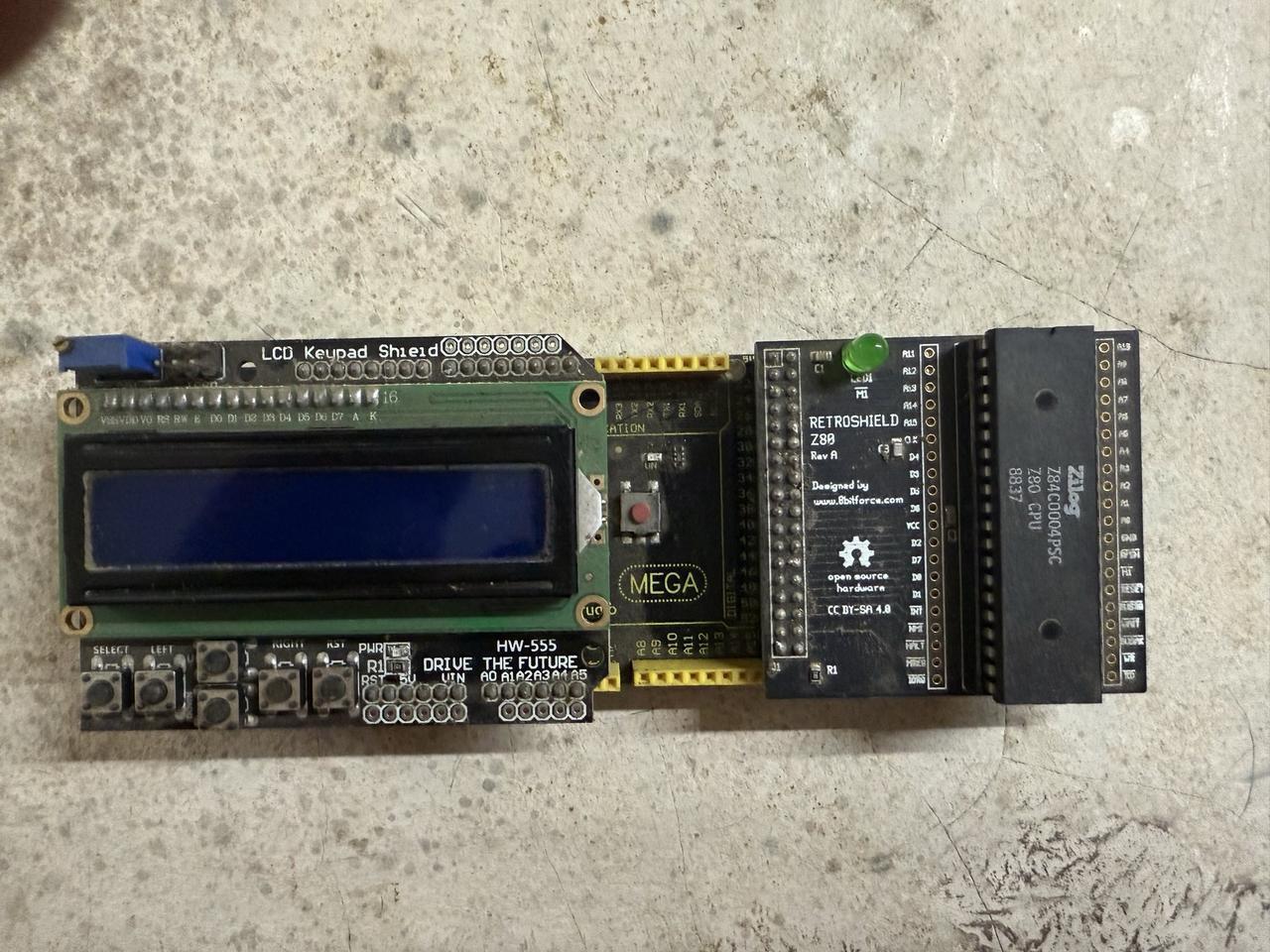

The Hardware Up Close

Here's my RetroShield Z80 setup with the Teensy adapter:

The Zilog Z80 CPU sits in the 40-pin DIP socket, with the Teensy 4.1 providing memory emulation and I/O handling beneath.

The physical hardware runs identically to the browser emulator above - the same ROMs, the same interpreters, the same authentic Z80 execution.

Why Build a Browser Emulator?

Having built several interpreters and tools for the RetroShield, I found myself constantly cycling through the development loop: edit code, compile, flash to Arduino, test, repeat. A software emulator would speed this up significantly, but I also wanted something I could share with others who might not have the hardware.

WebAssembly seemed like the perfect solution. It runs at near-native speed in any modern browser, requires no installation, and can be embedded directly in a web page. Someone curious about retro computing could try out a Fortran 77 interpreter or Forth environment without buying any hardware.

Building the Emulator in Rust

I chose Rust for the emulator implementation for several reasons:

-

Excellent WASM support: Rust's

wasm-bindgenandwasm-packtools make compiling to WebAssembly straightforward - Performance: Rust compiles to efficient code, important for cycle-accurate emulation

- The rz80 crate: Andre Weissflog's rz80 provides a battle-tested Z80 core

The emulator architecture is straightforward:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ Web Browser │ │ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │ │ JavaScript/HTML │ │ │ │ - Terminal display with CRT effects │ │ │ │ - Keyboard input handling │ │ │ │ - ROM loading and selection │ │ │ └─────────────────────┬─────────────────────┘ │ │ │ wasm-bindgen │ │ ┌─────────────────────▼─────────────────────┐ │ │ │ Rust/WebAssembly Core │ │ │ │ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────┐ │ │ │ │ │ rz80 CPU │ │ Memory (64KB) │ │ │ │ │ │ Emulation │ │ ROM + RAM │ │ │ │ │ └─────────────┘ └─────────────────────┘ │ │ │ │ ┌─────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │ │ │ │ I/O Emulation │ │ │ │ │ │ - MC6850 ACIA (ports $80/$81) │ │ │ │ │ │ - Intel 8251 USART (ports $00/$01) │ │ │ │ │ └─────────────────────────────────────┘ │ │ │ └───────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Dual Serial Chip Support

One challenge was supporting ROMs that use different serial chips. The RetroShield ecosystem has two common configurations:

MC6850 ACIA (ports $80/$81): Used by many homebrew projects including MINT, Firth Forth, and my own Fortran and Pascal interpreters. The ACIA has four registers (control, status, transmit data, receive data) mapped to two ports, with separate read/write functions per port.

Intel 8251 USART (ports $00/$01): Used by Grant Searle's popular BASIC port and the EFEX monitor. The 8251 is simpler with just two ports - one for data and one for control/status.

The emulator detects which chip to use based on ROM metadata and configures the I/O handlers accordingly.

Memory Layout

The standard RetroShield memory map looks like this:

| Address Range | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|

$0000-$7FFF |

32KB | ROM/RAM (program dependent) |

$8000-$FFFF |

32KB | Extended RAM (Teensy adapter) |

Most of my interpreters use a layout where code occupies the lower addresses and data/stack occupy higher memory. The Fortran interpreter, for example, places its program text storage at $6700 and variable storage at $7200, with the stack growing down from $8000.

The CRT Effect

No retro computing experience would be complete without the warm glow of a CRT monitor. I implemented several visual effects using pure CSS:

Scanlines: A repeating gradient overlay creates the horizontal line pattern characteristic of CRT displays:

.crt-container::before { background: linear-gradient( rgba(18, 16, 16, 0) 50%, rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.25) 50% ); background-size: 100% 4px; }

Chromatic aberration: CRT displays have slight color fringing due to the electron beam hitting phosphors at angles. I simulate this with animated text shadows that shift red and blue components:

@keyframes textShadow { 0% { text-shadow: 0.4px 0 1px rgba(0,30,255,0.5), -0.4px 0 1px rgba(255,0,80,0.3); } /* ... animation continues */ }

Flicker: Real CRTs had subtle brightness variations. A randomized opacity animation creates this effect without being distracting.

Vignette: The edges of CRT screens were typically darker than the center, simulated with a radial gradient.

The font: I'm using the Glass TTY VT220 font, a faithful recreation of the DEC VT220 terminal font from the 1980s. It's public domain and adds significant authenticity to the experience.

The Language Interpreters

The emulator comes pre-loaded with several language interpreters, each running as native Z80 code:

Fortran 77 Interpreter

This is my most ambitious RetroShield project: a subset of Fortran 77 running interpretively on an 8-bit CPU. It supports:

- REAL numbers via BCD (Binary Coded Decimal) floating point with 8 significant digits

- INTEGER and REAL variables with implicit typing (I-N are integers)

- Arrays up to 3 dimensions

- DO loops with optional STEP

- Block IF/THEN/ELSE/ENDIF statements

- SUBROUTINE and FUNCTION subprograms

- Intrinsic functions: ABS, MOD, INT, REAL, SQRT

Here's a sample session:

FORTRAN-77 Interpreter v0.3 RetroShield Z80 Ready. > PROGRAM FACTORIAL INTEGER I, N, F N = 7 F = 1 DO 10 I = 1, N F = F * I 10 CONTINUE WRITE(*,*) N, '! =', F END Program entered. Type RUN to execute. > RUN 7 ! = 5040

The interpreter is written in C and cross-compiled with SDCC. At roughly 21KB of code, it pushes the limits of what's practical on the base RetroShield, which is why it requires the Teensy adapter.

MINT (Minimal Interpreter)

MINT is a wonderfully compact stack-based language. Each command is a single character, making it incredibly memory-efficient:

> 1 2 + . 3 > : SQ D * ; > 5 SQ . 25

Firth Forth

A full Forth implementation by John Hardy. Forth's stack-based paradigm and extensibility made it popular on memory-constrained systems:

> : FACTORIAL ( n -- n! ) 1 SWAP 1+ 1 DO I * LOOP ; > 7 FACTORIAL . 5040

Grant Searle's BASIC

A port of Microsoft BASIC that provides the classic BASIC experience:

Z80 BASIC Ver 4.7b Ok > 10 FOR I = 1 TO 10 > 20 PRINT I * I > 30 NEXT I > RUN 1 4 9 ...

Technical Challenges

Building this project involved solving several interesting problems:

Memory Layout Debugging

The Fortran interpreter crashed mysteriously when entering lines with statement labels. After much investigation, I discovered the CODE section had grown to overlap with the DATA section. The linker was told to place data at $5000, but code had grown past that point. The fix was updating the memory layout to give code more room:

# Before: code overlapped data LDFLAGS = --data-loc 0x5000 # After: proper separation LDFLAGS = --data-loc 0x5500

This kind of bug is particularly insidious because it works fine until the code grows past a certain threshold.

BCD Floating Point

Implementing floating-point math on a Z80 without hardware support is challenging. I chose BCD (Binary Coded Decimal) representation because:

- Exact decimal representation: No binary floating-point surprises like 0.1 + 0.2 != 0.3

- Simpler conversion: Reading and printing decimal numbers is straightforward

- Reasonable precision: 8 BCD digits give adequate precision for an educational interpreter

Each BCD number uses 6 bytes: 1 for sign, 1 for exponent, and 4 bytes holding 8 packed decimal digits.

Cross-Compilation with SDCC

The Small Device C Compiler (SDCC) targets Z80 and other 8-bit processors. While it's an impressive project, there are quirks:

- No standard library functions that assume an OS

- Limited optimization compared to modern compilers

- Memory model constraints require careful attention to data placement

I wrote a custom crt0.s startup file that initializes the stack, sets up the serial port, and calls main().

Running the Emulator

The emulator runs at roughly 3-4 MHz equivalent speed, depending on your browser and hardware. This is actually faster than the original Z80's typical 4 MHz, but the difference isn't noticeable for interactive use.

To try it:

- Visit the Z80 Emulator page

- Select a ROM from the dropdown (try Fortran 77)

- Click "Load ROM"

- Click on the terminal to focus it

- Start typing!

For Fortran, try entering a simple program:

PROGRAM HELLO WRITE(*,*) 'HELLO, WORLD!' END

Then type RUN to execute it.

What's Next

There's always more to do:

- More ROM support: Expanding to additional retro languages like LISP, Logo, or Pilot

- Debugger integration: Showing registers, memory, and allowing single-stepping

- Save/restore state: Persisting the emulator state to browser storage

- Mobile support: Touch-friendly keyboard for tablets and phones

Source Code and Links

Everything is open source:

- Emulator source (Rust/WASM)

- Fortran interpreter source

- RetroShield hardware designs

- RetroLang compiler - my custom language for Z80

The RetroShield hardware is available from 8bitforce on Tindie.

Acknowledgments

- Erturk Kocalar - Creator of the RetroShield platform

- Andre Weissflog - Author of the rz80 Z80 emulator core

- Grant Searle - Z80 BASIC and reference designs

- John Hardy - Author of Firth Forth, MINT, and Monty

There's something magical about running 49-year-old CPU architectures in a modern web browser. The Z80 powered countless home computers, embedded systems, and arcade games. With this emulator, that legacy is just a click away.