Introduction and Overview

Field programmable gate arrays occupy a fascinating position in the landscape of digital electronics: immensely powerful, endlessly flexible, and yet stubbornly inaccessible to newcomers. Unlike microcontrollers, which have benefited from decades of beginner-friendly ecosystems like Arduino and Raspberry Pi, FPGAs have long remained the province of electrical engineering graduates and industry professionals. The learning curve is steep, the toolchains are complex, and the fundamental paradigm shift from sequential software thinking to parallel hardware description is enough to discourage many aspiring digital designers before they write their first line of HDL. Russell Merrick's Getting Started with FPGAs: Digital Circuit Design, Verilog, and VHDL for Beginners, published by No Starch Press in 2024, makes a deliberate and largely successful attempt to change that.

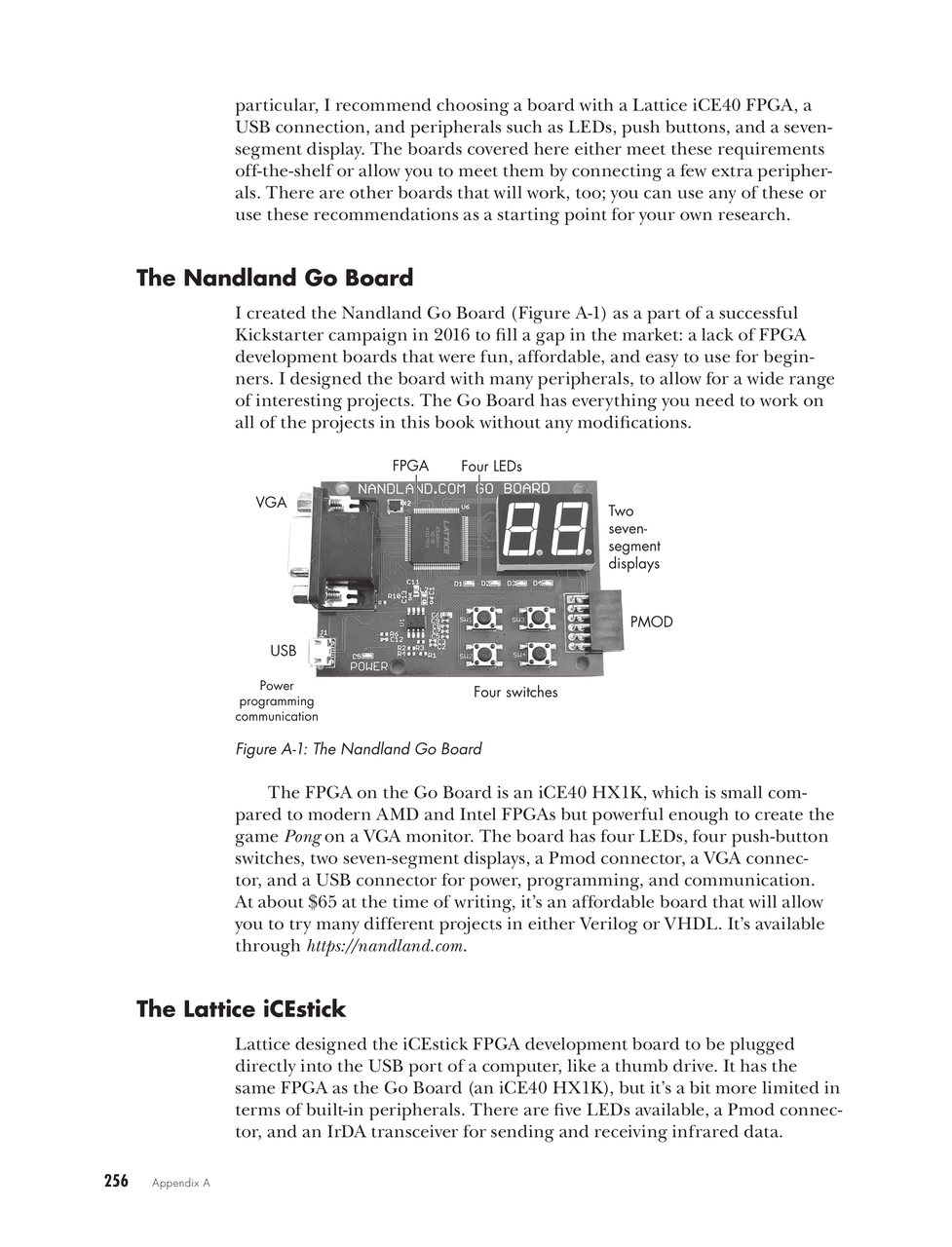

Merrick brings a distinctive combination of credentials to this task. A University of Massachusetts electrical engineering graduate with a master's degree in the same field, he has worked in defense at BAE Systems and L-3 Communications, in aerospace at satellite propulsion startup Accion Systems, and in commercial electronics at fitness wearable company WHOOP. More importantly for a book of this nature, he has been creating FPGA educational content at nandland.com and its accompanying YouTube channel since 2014, even designing his own FPGA development board, the Nandland Go Board. This decade of answering beginner questions on Stack Overflow and producing tutorial content informs every page of the book. Merrick knows exactly where newcomers get stuck, because he has been watching them get stuck for years.

The book spans 11 chapters plus two appendices across roughly 280 pages, targeting the Lattice iCE40 family of FPGAs. This choice of hardware is itself a pedagogical decision: iCE40 devices are inexpensive, the toolchain (iCEcube2 and Diamond Programmer) is lightweight, and the open source community has embraced Lattice parts for low-level hacking. More expensive FPGAs from AMD (Xilinx) or Intel (Altera) come with sophisticated but overwhelming development environments that can intimidate beginners. By choosing the simpler end of the market, Merrick keeps the focus on understanding FPGA fundamentals rather than wrestling with tool complexity.

The Dual-Language Approach

Perhaps the most distinctive pedagogical choice in the book is Merrick's decision to present every code example in both Verilog and VHDL, side by side. This is no small commitment for an author. It effectively doubles the code content of the book and requires careful attention to ensure that both versions are correct, idiomatic, and illustrative of the same concepts. The payoff, however, is substantial: readers can follow along with whichever language suits their situation without needing to purchase a second book or mentally translate between the two.

Merrick provides a thoughtful comparison of the two languages in Chapter 1 that avoids the partisan flame wars common in FPGA circles. He notes that VHDL, born from the U.S. Department of Defense and inheriting Ada's strong typing, requires more verbose code but catches errors at compile time. Verilog, syntactically closer to C and weakly typed, is more concise but will happily let you write incorrect code without complaint. He even includes a Google Trends analysis showing regional preferences: Verilog dominates in the United States, China, and South Korea, while VHDL is preferred in Germany and France. His practical advice is refreshingly simple: learn whichever language your school or employer uses.

The dual-language presentation also serves as an implicit lesson in the differences between the two HDLs. Readers can observe firsthand how VHDL's strong typing forces explicit resize() calls and type conversions that Verilog handles automatically, or how VHDL's process blocks map to Verilog's always blocks. These side-by-side comparisons provide a deeper understanding of both languages than either one alone could offer.

Building Foundations: Logic, Memory, and Time

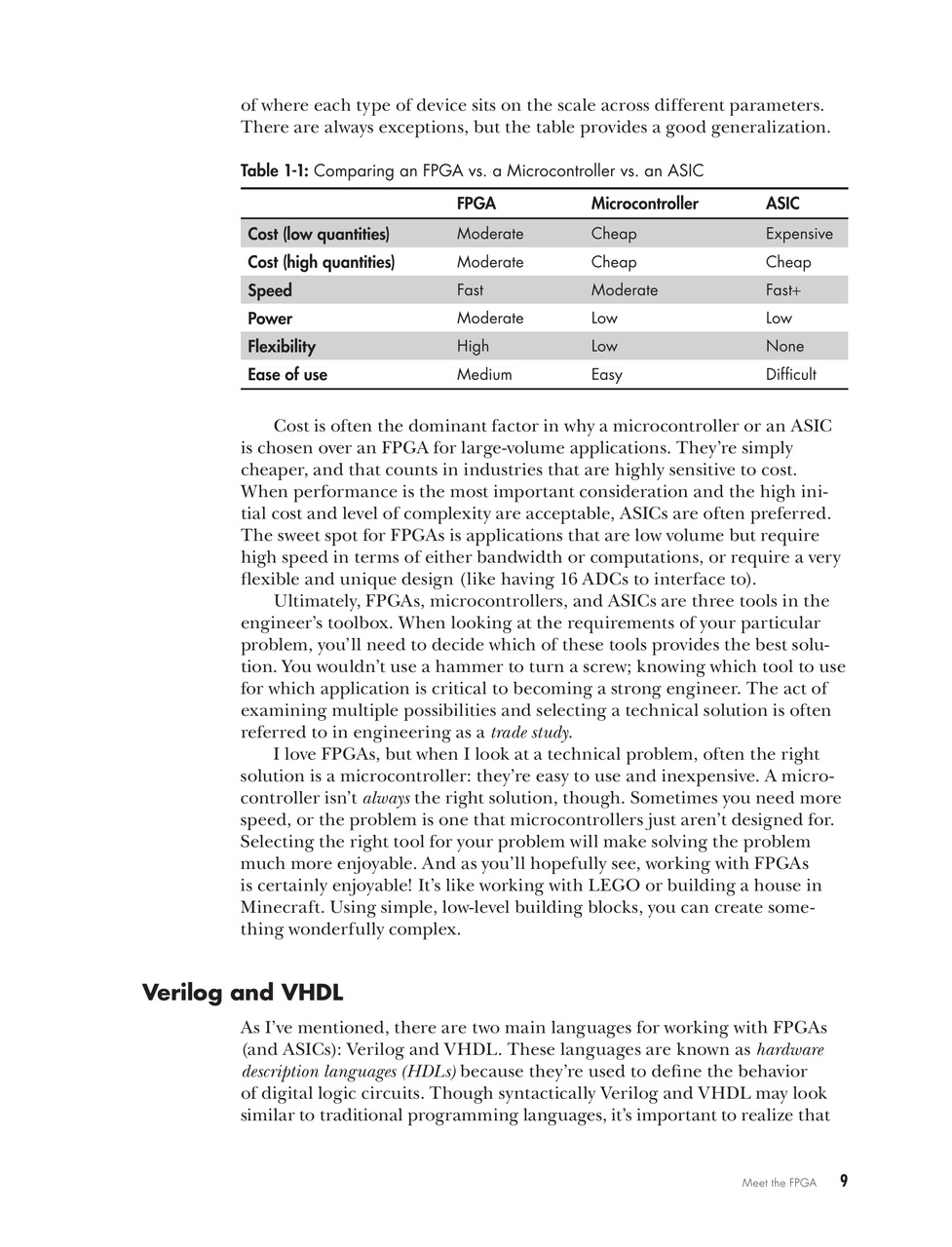

The book's first four chapters establish the fundamental building blocks of FPGA design with admirable clarity. Chapter 1, "Meet the FPGA," provides historical context starting from the Xilinx XC2064 in 1985 and surveys the modern FPGA landscape, including the AMD acquisition of Xilinx for $35 billion and Intel's earlier purchase of Altera for $16.7 billion. The chapter's comparison of FPGAs versus microcontrollers versus ASICs across dimensions of cost, speed, power, flexibility, and ease of use is presented in a clean table that serves as a useful reference throughout the reader's career. Merrick is honest about where FPGAs fall short: they are more expensive than microcontrollers at scale, consume more power, and are harder to use. But when you need raw bandwidth, parallel computation, or hardware flexibility, nothing else will do.

Chapter 2 walks through hardware and tool setup, getting readers to their first working FPGA project: wiring switches to LEDs. This "hello world" equivalent may seem trivial, but it introduces the full development workflow: writing HDL code, creating a project, adding pin constraints, running the build, connecting the board, and programming the FPGA. Each step is a potential stumbling block for beginners, and Merrick guides through them methodically.

Chapter 3 on Boolean algebra and the look-up table is where the book begins to reveal its deeper ambitions. Rather than treating logic gates as abstract mathematical curiosities, Merrick connects them directly to the physical reality inside an FPGA. The key insight, clearly articulated, is that discrete logic gates do not actually exist inside modern FPGAs. Instead, all Boolean operations are implemented through look-up tables, programmable devices that can represent any truth table you can imagine. A single three-input LUT can replace an AND gate, an OR gate, an XOR gate, or any combination thereof. This understanding, that LUTs and flip-flops are the two fundamental building blocks from which all FPGA designs are constructed, is the conceptual foundation upon which the entire book rests.

Chapter 4 introduces the flip-flop and with it the concept of state. Where LUTs handle combinational logic, flip-flops provide sequential logic, giving the FPGA memory of what happened previously. The chapter carefully distinguishes between combinational and sequential logic, explains the clock signal and its role in synchronizing operations, and warns about the dangers of latches, an accidental design pattern that causes unpredictable timing behavior. Merrick's years of answering beginner questions are evident here; the latch warning, including the specific synthesis warning message readers should watch for, addresses one of the most common FPGA beginner mistakes.

Simulation, Testing, and the Black Box Problem

Chapter 5, on simulation, contains some of the book's most valuable practical wisdom. Merrick frames the motivation perfectly: your FPGA is essentially a black box. You can change the inputs and observe the outputs, but you cannot see what is happening inside. Simulation cracks open that black box, letting you examine every internal signal, register, and wire as your design executes.

He drives this point home with an anecdote from his professional experience: a coworker spent weeks debugging an FPGA design using oscilloscopes and logic analyzers, trying to find a data corruption issue on the physical hardware. Merrick checked the code out, built a simulation testbench, and found the bug within hours. The lesson is clear: simulation is not an optional nicety but an essential part of the FPGA development process that will save you enormous amounts of time.

The chapter introduces EDA Playground, a free web-based simulator, as the primary tool. This is a pragmatic choice that eliminates the barrier of downloading and configuring multi-gigabyte vendor tools. Readers learn to write testbenches, the HDL code that exercises a design by providing inputs and monitoring outputs. The first testbench, for the AND gate project from Chapter 3, walks through every detail: declaring signals, instantiating the unit under test, driving stimulus with delay statements, and generating waveform output for visual analysis. The progression to more sophisticated testing, including self-checking testbenches that automatically verify correctness and a discussion of formal verification, shows that Merrick understands the professional importance of testing even as he keeps the material accessible.

Common Modules and the Building-Block Philosophy

Chapter 6, "Common FPGA Modules," represents a turning point in the book's complexity. Having established the primitive components, LUTs and flip-flops, Merrick now shows how to combine them into reusable building blocks: multiplexers, demultiplexers, shift registers, RAM, and FIFOs. Each module is explained conceptually, implemented in both Verilog and VHDL, and connected to practical applications.

The FIFO (First In, First Out) implementation is particularly well done. Merrick walks through the complete design including read and write address management, element counting, full and empty flags, and "almost full" and "almost empty" threshold flags. The code is production-quality, handling edge cases like simultaneous read and write operations and providing anticipatory flags that let higher-level modules stop writing before the FIFO actually overflows. This is not a toy example; it is a genuinely useful piece of infrastructure that readers can adapt for their own projects.

The Linear Feedback Shift Register (LFSR) implementation showcases a more specialized application: generating pseudo-random sequences using nothing more than shift registers and XOR gates. Merrick explains why this matters in practice, as LFSRs are used in everything from encryption to test pattern generation, and provides the implementation alongside a conceptual explanation of why specific feedback tap positions produce maximum-length sequences.

The Build Process Demystified

Chapter 7 tackles synthesis, place and route, and crossing clock domains, subjects that many beginner texts either skip or relegate to appendices. Merrick treats them as essential knowledge, and rightly so. Understanding what happens when you press the "Build FPGA" button is critical for writing efficient, correct designs.

The synthesis discussion is particularly strong. Merrick explains logic optimization, the tool's process of minimizing the resources your design consumes, and connects it to the utilization report that tells you how many LUTs, flip-flops, and block RAMs your design uses. He provides practical guidance on what to do when your design does not fit: switch to a larger FPGA, rewrite resource-intensive modules, or remove functionality. His anecdote about a division operation that forced a million-dollar hardware upgrade to a larger FPGA family illustrates the real-world consequences of resource-intensive code.

The section on non-synthesizable code addresses a source of deep confusion for beginners transitioning from software: not all valid Verilog or VHDL code can be translated into physical hardware. Time delays, print statements, file operations, and certain loop constructs exist solely for simulation and will be silently ignored or flagged during synthesis. Merrick's treatment of synthesizable versus non-synthesizable for loops is especially valuable. In software, a for loop iterates sequentially over time. In synthesizable FPGA code, a for loop unrolls into replicated hardware that executes simultaneously in a single clock cycle. Beginners who expect a 10-iteration loop to take 10 clock cycles will be baffled when it completes in one. Merrick shows both the pitfall and the correct pattern for implementing sequential iteration using counters and if statements.

The clock domain crossing section covers a topic that trips up even experienced FPGA designers. When signals pass between parts of a design running at different clock frequencies, metastability can cause unpredictable behavior. Merrick explains the problem and presents standard solutions: double-flop synchronizers for single-bit signals and FIFOs for multi-bit data transfers.

State Machines and the Memory Game

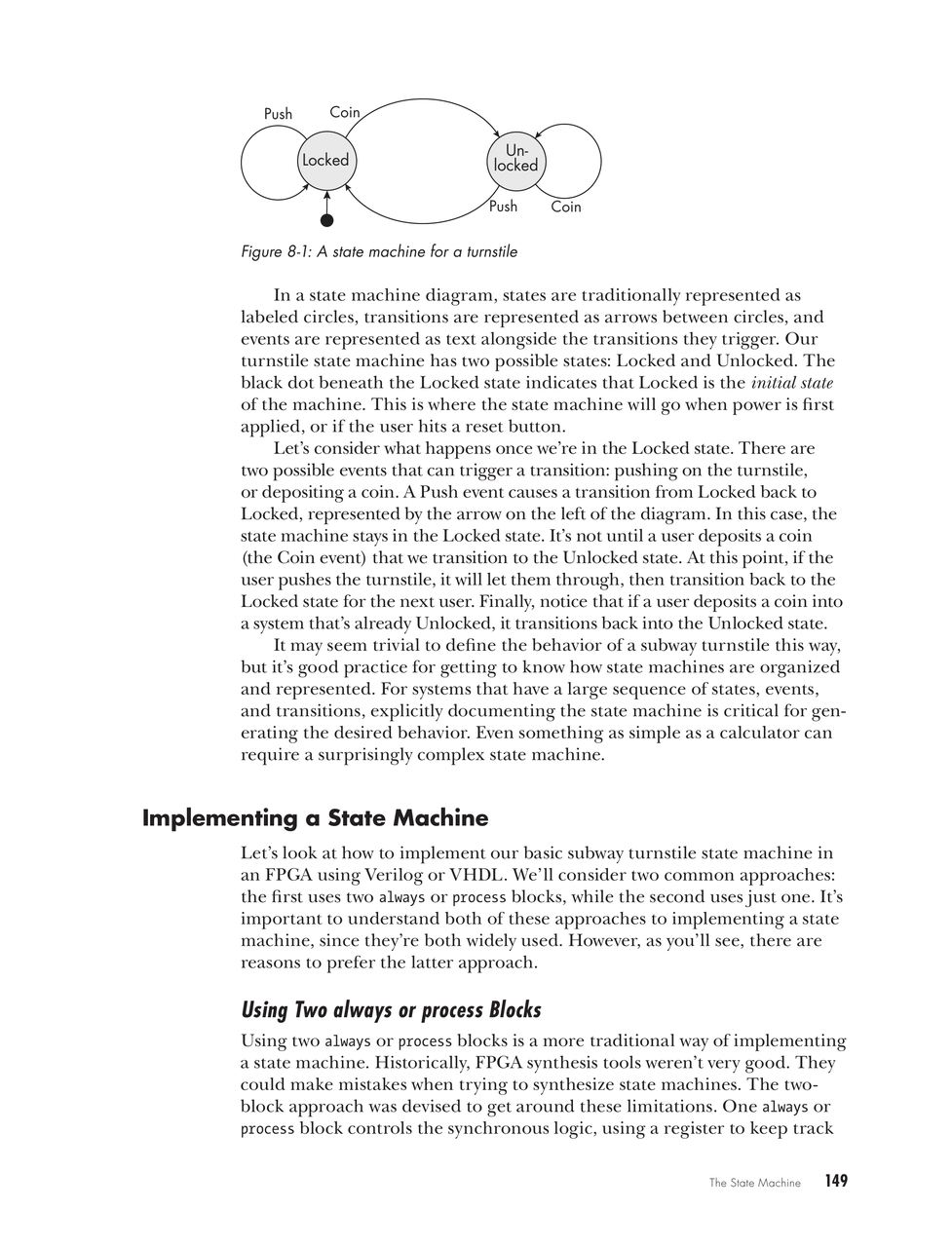

Chapter 8, "The State Machine," brings together all the preceding material in the book's most ambitious project: an interactive memory game using a seven-segment display. State machines are the standard way to implement sequential behavior in FPGAs, a series of states connected by transitions triggered by events. Merrick presents two implementation styles (two-process and one-process blocks), discusses best practices, and then launches into a full project that requires planning the state machine, organizing the design across multiple modules, interfacing with a seven-segment display, and writing comprehensive testbenches.

The memory game project is a strong capstone for the book's middle section. It requires the reader to synthesize knowledge of flip-flops, multiplexers, RAM, state machines, and physical I/O constraints into a working interactive system. The project is complex enough to feel like genuine FPGA engineering but simple enough to complete without despair.

FPGA Primitives and the Hardware Reality

Chapter 9 examines the specialized hardware blocks that differentiate FPGAs from simple arrays of LUTs and flip-flops. Block RAM provides dedicated memory resources that are faster and more efficient than flip-flop-based storage. The Digital Signal Processing (DSP) block offers hardened multiply-accumulate units that are essential for math-intensive applications like filtering and signal processing. The Phase-Locked Loop (PLL) generates new clock frequencies from an input clock, enabling designs that need multiple clock domains.

Merrick explains both the capabilities and the creation process for each primitive, covering both instantiation (directly connecting to the hardware block in your code) and the GUI approach (using vendor tools to configure the block graphically). This dual treatment acknowledges that different workflows suit different situations and different engineers.

Numbers, Math, and the Rules of Binary Arithmetic

Chapter 10, "Numbers and Math," is arguably the most technically dense chapter in the book, and it may also be the most practically valuable. Performing mathematical operations inside an FPGA is fraught with subtle pitfalls that can produce silently incorrect results. Merrick distills years of hard-won experience into six clear rules that, if followed, will prevent the most common binary math errors.

The chapter progresses methodically through addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, showing both correct and incorrect implementations at each step. The emphasis on showing code that produces wrong answers is a particularly effective teaching strategy. When Merrick demonstrates that adding two 4-bit unsigned numbers (9 + 11) and storing the result in a 4-bit output gives 4 instead of 20, the reader understands viscerally why Rule #1 (the result should be at least 1 bit bigger than the biggest input) matters. The discussion of sign extension, the process of increasing a binary number's bit width while preserving its sign and value, is handled with exceptional clarity.

The treatment of division is refreshingly honest. Merrick states plainly that division is resource-intensive and should be avoided when possible inside an FPGA. He presents three alternatives: restricting divisors to powers of 2 (implemented as simple shift-right operations), using precalculated lookup tables stored in block RAM, and spreading the operation across multiple clock cycles using iterative subtraction. His anecdote about "the million-dollar divide," where a single division operation forced an upgrade to a more expensive FPGA family at a cost exceeding $1 million in hardware changes, makes the point memorably.

The fixed-point arithmetic section that closes the chapter is an excellent primer on representing decimal values in hardware without the complexity and resource cost of floating-point. Merrick introduces the UX.Y and SX.Y notation for unsigned and signed fixed-point formats, explains the conversion between formats, and works through addition and multiplication examples that demonstrate the rules for matching decimal widths and sizing outputs.

I/O, SerDes, and the Edge of the Chip

The final technical chapter covers getting data in and out of the FPGA, where the digital logic meets the physical world. Merrick covers GPIO pin configuration including I/O buffers, output enable signals, and bidirectional communication. He explains operating voltage standards (LVCMOS33, TTL, LVCMOS25), drive strength in milliamps, and slew rate, the speed at which a signal transitions between high and low. The discussion of single-ended versus differential signaling provides useful background for understanding high-speed interfaces.

The SerDes (serializer/deserializer) section introduces the concept of converting parallel data to serial for high-speed transmission and back again at the receiver. While the iCE40 FPGAs used in the book's projects do not include SerDes blocks, Merrick covers the topic at a conceptual level to prepare readers who may eventually work with more capable devices. This forward-looking coverage, explaining concepts that exceed the current hardware's capabilities, is a sensible choice that increases the book's long-term value.

The Appendices: Beyond the Technical

Appendix A surveys three development boards compatible with the book's projects: the Nandland Go Board, the Lattice iCEstick, and the Alchitry Cu. The Nandland Go Board, designed by Merrick himself, is naturally the most fully supported option, but the inclusion of alternatives from other vendors demonstrates good faith.

Appendix B, "Tips for a Career in FPGA Engineering," is an unusual and welcome addition to a technical book. Merrick covers resume construction, interview preparation, and job offer negotiation with the practical specificity of someone who has been on both sides of the hiring table. He advises listing HDL projects prominently on resumes, preparing for whiteboard coding exercises in Verilog or VHDL, and understanding that FPGA engineering positions often command premium salaries due to the specialized skill set. For readers considering FPGA development as a career rather than a hobby, this appendix alone could be worth the price of the book.

Strengths and Unique Value

The book's greatest strength is its accessibility. Merrick has an uncommon talent for explaining hardware concepts in software-friendly terms without being condescending or imprecise. His comparison of low-level FPGA programming to building with individual LEGO bricks while high-level microcontroller programming is like working with preconstructed LEGO sets captures the essential difference in a way that immediately resonates. The parallel-versus-serial thinking distinction, hammered home from the first chapter, is the single most important conceptual hurdle for software developers entering FPGA territory, and Merrick addresses it directly and repeatedly.

The hands-on projects embedded throughout the book, from wiring switches to LEDs through blinking an LED, debouncing a switch, selectively blinking LEDs, and building a memory game, provide a satisfying progression of complexity. Each project builds on concepts from previous chapters and results in something that works on real hardware, providing the tangible feedback that keeps learners motivated.

The dual Verilog/VHDL presentation is a genuine differentiator. Most FPGA books choose one language and leave readers of the other to fend for themselves. Merrick's commitment to both languages, while surely doubling his authorial workload, produces a reference that serves a broader audience and provides implicit comparative education that deepens understanding of both languages.

The inclusion of professional engineering wisdom, from the million-dollar divide anecdote to the latch warnings to the career advice appendix, gives the book a practical grounding that purely academic treatments lack. Merrick writes as someone who has shipped FPGA designs in defense, aerospace, and consumer electronics, and that experience informs his choices about what to emphasize and what to warn against.

Limitations and Missed Opportunities

The book's commitment to the iCE40 platform, while pedagogically sound, does impose limitations. These are small, inexpensive FPGAs with limited resources, no hard processor cores, and minimal specialized IP blocks. Readers who complete the book and want to tackle more ambitious projects, say, implementing a RISC-V soft processor or building a video processing pipeline, will need to transition to AMD or Intel FPGA platforms with significantly different (and more complex) toolchains. The book provides a conceptual foundation for that transition but no practical guidance through it.

The Windows-centric tooling requirement is a notable friction point. Merrick acknowledges that the iCE40 tools work best on Windows and recommends a virtual machine for Mac and Linux users. In an era when open source FPGA tools like Yosys and nextpnr have matured significantly, especially for iCE40 targets, the absence of any mention of the open source toolchain feels like a missed opportunity. For Linux users in particular, the Yosys/nextpnr/IceStorm flow provides a native, arguably simpler development experience than running Windows tools in a VM.

The book could benefit from more substantial treatment of debugging workflows. While simulation is covered well, on-FPGA debugging receives only brief mention. Topics like using integrated logic analyzers, reading back internal signals through JTAG, or structured approaches to narrowing down hardware bugs would strengthen the book's practical value for readers who move beyond simulation into real hardware deployment.

Some readers may find the book's pace in early chapters slow if they already have digital logic background from university courses. The extensive coverage of Boolean algebra, truth tables, and logic gates in Chapter 3, while valuable for true beginners, may feel redundant for readers with prior exposure. Conversely, the later chapters on clock domain crossing, SerDes, and fixed-point arithmetic accelerate considerably and could benefit from additional worked examples.

Who Should Read This Book

The book is best suited for three audiences. First, software developers who are curious about hardware and want to understand what happens below the abstraction layer of their programming languages. The explicit comparisons between software concepts (sequential execution, for loops, variables) and their FPGA counterparts (parallel execution, hardware replication, signals and registers) make this a natural bridge text. Second, electronics hobbyists and makers who have experience with microcontrollers like Arduino or Raspberry Pi and want to explore the next level of hardware control. Third, university students encountering FPGAs in coursework who need a more approachable companion text to supplement dense academic material.

Experienced FPGA engineers will find little new technical content here, though the book's explanations may provide useful language for mentoring junior colleagues. Readers looking for advanced topics like high-level synthesis, SystemVerilog verification methodology, or FPGA-based machine learning acceleration will need to look elsewhere.

Conclusion

Getting Started with FPGAs succeeds at its stated goal: building a solid foundation for anyone interested in the world of FPGA design. Russell Merrick has distilled a decade of educational content creation into a coherent, well-structured text that respects the reader's intelligence while acknowledging the genuine difficulty of the subject matter. The dual-language approach, the hands-on projects, the honest treatment of where FPGAs excel and where they fall short, and the professional engineering perspective all contribute to a book that fills a genuine gap in the FPGA literature.

The book does not attempt to be comprehensive. It will not teach you everything about Verilog or VHDL, will not prepare you to design a production FPGA system from scratch, and will not cover the full depth of any single topic it addresses. What it will do is give you a clear mental model of how FPGAs work at a fundamental level, equip you with enough Verilog and VHDL to write and simulate basic designs, and provide the conceptual vocabulary to continue learning independently. For a subject as intimidating as FPGA development, that is no small achievement.

In the broader context of No Starch Press's catalog of accessible technical books, Getting Started with FPGAs fits naturally alongside titles that demystify complex subjects without dumbing them down. It occupies a niche that has been surprisingly underserved: the true beginner FPGA book that takes the reader seriously. For anyone who has stared at an FPGA development board with a mixture of curiosity and trepidation, wondering how to bridge the gap between software thinking and hardware reality, this book provides a clear and well-lit path forward.